Australian (Warlpiri, Central/Western Desert), born 1955

Yanjirlpirri Jukurrpa (Star Dreaming), 2007

Acrylic on canvas, h. 35 13/16 in. (91 cm); w. 29 15/16 in. (76 cm)

Gift of the Lam Family, 2016.14.57

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VISCOPY, Australia

Photography by Peggy Tenison.

The captivating exhibition Of Country and Culture: The Lam Collection of Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, on view through May 14 at the San Antonio Museum of Art, kicks off with a notice to visitors that’s as startling as it is salutary.

“Many Indigenous Australians avoid naming and viewing images of the deceased,” the introductory text concludes. “We respectfully advise that some artists whose work is displayed in this exhibition, or whose names are mentioned in writing, have passed away.”

Regular museumgoers, particularly those who frequent exhibitions of African, pre-Columbian, or other art from indigenous cultures—are used to the idea that they’re violating the makers’ intentions by laying eyes upon whatever it is they’re looking at, let alone calling it art. Then there’s the consideration of how the art made it to the museum in the first place. You’ve got to price a fair amount of guilt into the experience of appreciating other cultures’ creativity, particularly when it addresses ideas of the sacred untethered to your own, or those of the culture that produced you.

But as SAMA’s visitor notice makes clear, although the seventy-five works on view were translated from ephemeral sand and body paintings, they were done so for the express purpose of participating in the international contemporary art market. Whatever else they may or may not have in common with the work of abstract painters and sculptors from elsewhere, the artworks shown here were made to be exhibited as such. (Even the works by deceased artists; the heads-up is for indigenous Australians, not for art-loving Texans, nomadic or otherwise.)

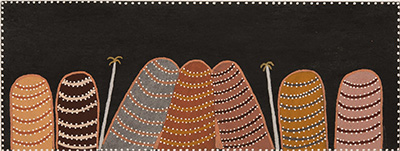

Australian (Gija, Kimberley), n.d.

Purnululu, 2007

Natural ochres and pigments on canvas, h. 17 11/16 in.; w. 47 ¼ in.

Gift of the Lam Family, 2016.14.51

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VISCOPY, Australia

Photography by Peggy Tenison.

And now, thanks to the collecting acumen and generosity of SAMA life trustee May Lam and her family, they are also part of what exhibition curators Lana Meador, curatorial assistant for modern and contemporary art, Erin Murphy, manager of exhibitions and assistant to the chief curator, believe to be among the top five or six museum collections of contemporary Australian Aboriginal art in the United States. One must look to the renowned Keir Collection of Islamic Art’s long-term loan to Dallas Museum of Art for a recent, similarly transformative act of generosity, but the Lam gift is arguably even more important for SAMA, given its permanence and the fact that it can be deployed both in stand-alone displays of Australian Aboriginal art and in dialogue with its international contemporary art holdings, which the gift also elevates and makes more distinctive. Adding to SAMA’s institutional bragging rights, the Lams’ passion for the field was sparked by the museum’s 2000 exhibition Spirit Country, which featured the collection of the Melbourne-based families Gantner and Myer.

Australian (Pintupi, Western and Central Desert), born 1956

Untitled, n.d.

Acrylic on linen, h. 60 ¼ in.; w. 48 1/16 in.

Gift of the Lam Family, 2016.14.68

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VISCOPY, Australia

Photography by Peggy Tenison.

None of this is to say that Meador and Murphy, neither of whom has been to Australia—or with the museum very long, for that matter—haven’t proceeded with appropriate caution. As newcomers to the material themselves, they sensed that a presentation organized geographically might not mean much to most visitors, so they laid out the show thematically; an introductory gallery is followed by sections on “the Dreaming”— a belief system connecting “all objects, lands, life forces, and beings —the land, ceremony, and mortality.”

As feminists, Meador and Murphy say it’s a welcome development that the show mostly includes women artists, but that fact is largely a reflection of quality.

“What the female artists were doing was—dare I say it?—more exciting than what the men were doing,” Murphy says. “The men were, I think, more tied to traditional paintings of things. … You’ll see that the usage of color, the sheer abstraction and almost dynamism of the works by the female artists—I mean, you can’t help but respond.”

As is true of so many avant-gardes, the first decade or so of Australian Aboriginal forays into making portable, permanent, marketable artworks, the 1970s, was male-dominated, with men’s Dreamings and ceremonies the only permissible subject matter—and men typically the only painters, though some women served in apprenticeships under men. But as women began painting based on their own Dreamings, ceremonies, cultural practices, initiations, and fertility-related concerns, “they pushed the envelope more,” Meador says.

For example, Eubenia Nampitjin was in her fifties when she joined the contemporary painting movement in 1986, just a few years after the senior men in her community voted to allow women to participate. After painting with her second husband for a period, she set out on her own. Named for an ancestral mother dog, Nampitjin’s luscious, mostly pink 2007 painting Kinyu depicts the ubiquitous sand hills of her country; tiny circles near the top refer to the water sites where Kinyu resides. But as Meador notes, Nampitjin’s painting resonates visually with works from SAMA’s collection by Helen Frankenthaler and Richard Diebenkorn.

Australian (Gija, Kimberley), born 1948

Purnululu, 2007

Natural ochre and pigments on canvas, h. 35 7/16 in.; w. 47 ¼ in.

Gift of the Lam Family, 2016.14.50

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VISCOPY, Australia

Photography by Peggy Tenison.

That’s not to say that the works in this exhibition—one of those most visually electrifying I’ve seen at SAMA—are only important to the extent that they remind us of European or American painting. But the Lam gift seems to dovetail especially nicely with SAMA’s particular niche as perhaps the least Eurocentric of American encyclopedic museums while expanding both the quality and scope of its contemporary art collection.

Indeed, it may also complicate its meaning. If their imagery comes from sand and body painting and from ritual, and Australian Aborigines avoid naming or viewing images of the deceased, that suggests we are dealing with art that is both made for collecting institutions and flies in the face of their purpose. In that respect, indigenous Australians may make the most genuinely contemporary art of all.

—DEVON BRITT-DARBY