When you think about racial justice, a house may not come to mind. Maybe the Juanita J. Craft Civil Rights House, named for the late civil rights activist in Dallas. But do you think it’s a space for liberation only because her name is on it?

One University of Texas at Austin architecture professor thinks so.

Charles L. Davis II, an associate professor of architectural history and criticism at UT Austin’s School of Architecture, researches the relationship between race and place. His research into how race and ethnicity shape and hinder the built environment –– the broad term used to describe human-designed structures and systems –– culminated in grants from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts and Arnold W. Brunner Grant for a series of exhibits and programming beginning this fall at the university.

“They just didn’t fit into this same nice, neat definition of the architect,” Davis said. “It’s almost impossible to think about Black activism without thinking about the built environment, space and architecture. But because we’re focused on professionalism, we tend to look at those who are licensed. For me it’s a way to broaden the way we look at the studios but for me also in the practice.”

His framework brings together the concepts of the “activist-builder” and “artist-developer,” a term coined by Aisha Densmore-Bey to describe the public health benefits of artist-led community development. Her recent study for the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University described Project Row Houses as an excellent case study for alternative models of community development.

1 ⁄7

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

2 ⁄7

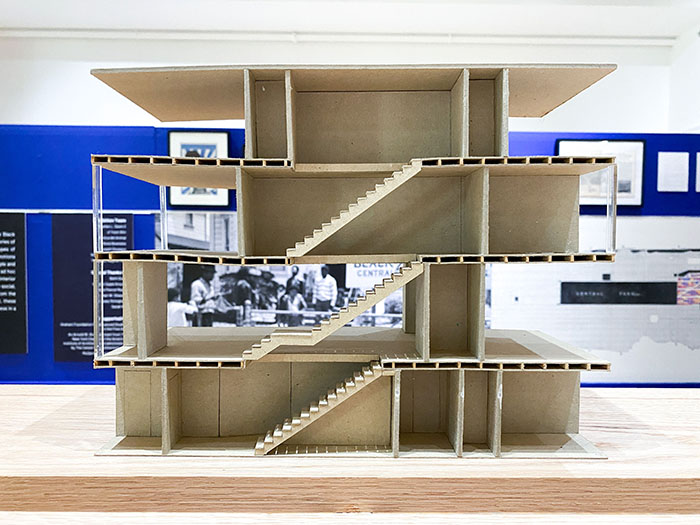

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

3⁄ 7

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

4 ⁄7

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

5 ⁄7

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

6 ⁄7

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

7 ⁄7

Installation View: The Black Home as Public Art, exhibition organized by Charles L. Davis II. Photo credit: Anya Mitchell, courtesy The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

They’re all in existing neighborhoods, and each have their own character. Assembling a show based on a theory may have limited appeal and only of interest to academics. But there is so much to see, and so much to take away.

Project Row Houses is portrayed in photographs by Keith Ewing. A large-scale photograph from the book The Heidelberg Project. Connecting the Dots: Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007) features a photograph of aging assembled vacuum cleaners on a lawn. Another photograph, “Crown Royal Bag” and “Ultrasheen,” 2020, come from Amanda Williams, Color(ed) Theory Suite photographed by Will Carson for aw|studio. But it, too, came from the groundbreaking book Black Futures, edited by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham (New York: One World, 2020).

Alongside them are vintage photographs and ephemera of the historic home the Black Panther Party transformed into a community center, excerpts from licensed architect and writer June Jordan’s writings about Harlem, portrayed in a graphic map created by Davis. Jordan’s words are realized with three-dimensional models designed with students include speculative projects, such as the brownstone depicted by June Jordan in her novella His Own Where.

The photographs may be familiar, or out of place in a gallery, but Davis’s curation adds context to the projects. He’s showing the varieties of ways a space can be activated.

“I’m trying to focus on the roots of architectural invention that can be traced back to space and space making, and the ways that Black activists and artists decide when architecture becomes a good meter for communicating what their cultural projects are, and what aspects of architecture fall to the side that are no longer useful,” he said.

The archives ideally could serve as a resource for architects and the public to learn about these alternative practices.

“What’s interesting about these folks is that they offer an alternative model of practice. Whereas the traditional architect waits for a client to come to them. Then they fly in, become an expert, make the project, and then they disappear,” he said. “These artists live in these spaces, and they continue to produce work in those spaces. The architecture becomes a living monument of the evolving state of the neighborhood and involves multiple cycles of community engagement and activism. I think that that’s a model of practice.”

—JAMES RUSSELL