Pollution is a constant presence in places like Houston, one that sinks into the background of our everyday lives becoming all too tolerable until we receive severe reminders of the impact. These reminders take many forms, one of the most common being fires and explosions at the plants embedded in neighborhoods around the Greater Houston Area.

Curated by Ashley DeHoyos Sauder, River on Fire draws on the significance of the history surrounding these events and their impact on our understanding of ecological preservation and environmental advocacy. The exhibition is on view at DiverseWorks in Houston from Sept. 28 to Nov. 16, in connection with the 2024 Texas Biennial.

“A lot of the conversation around environmentalism is relatively young, coming out in the 1970s and the EPA resulting from some of the river fires,” DeHoyos Sauder stated, referencing the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio, which caught fire multiple times throughout the 20th century. The most infamous of these fires occurred in 1969 when the fire gained national attention and fostered public outrage.

“There’s a lot of history around this, and one thing I found is that Houston has a long history of artists talking about these issues,” DeHoyos Sauder explained. “The work I’m doing is to connect and name some of these historical artists and organizations because there’s a lack of visibility.”

Like many other areas in the United States and across the globe, the Gulf Coast of Texas is dominated by industry, resulting in land and water contamination. In areas like Houston, a lack of zoning laws results in neighborhoods popping up in polluted areas near plants and factories, leaving residents to grapple directly with health hazards. Across the board, there’s a broader impact to consider as environmental disasters grow in severity amidst the climate crisis.

“Living among industries in Houston, there are higher rates of cancer and respiratory issues,” DeHoyos Sauder said. “We want to engage with those stories without that being the sole focus. Living on these fencelines is an act of survival and perseverance, and part of what we’ve had conversations about internally has been asking what is the balance between the joy and the sorrow?”

1 ⁄6

Manuel Alejandro Rodríguez-Delgado, Jíbaro, 2023, courtesy the artist and the Canary Test.

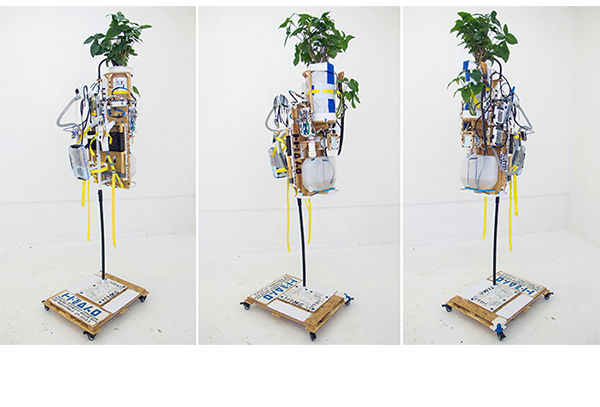

2 ⁄6

Laura Napier, Watersheds, 2024, courtesy of the artist.

3 ⁄6

Carolina Aranibar-Fernández, Sembrando, 2024. Image credit: Gabby Usinger, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art.

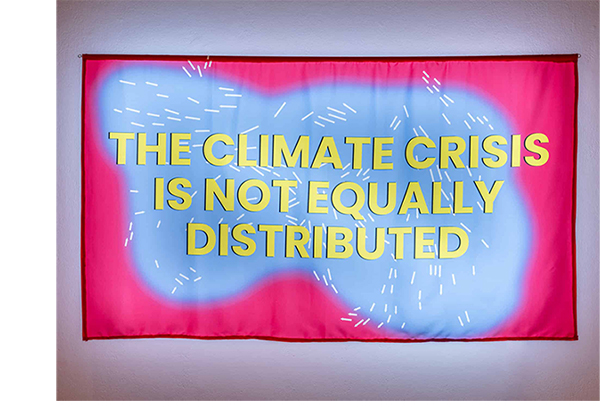

4 ⁄6

Christina Battle the air we breathe, 2023. Exhibition documentation by Darren Rigo, Courtesy of Gallery 44 (Toronto).

5 ⁄6

Hanna Chalew, Feedback LOOP, 2022, courtesy of the artist.

6 ⁄6

Joe Robles, Deer Park ITC Fire, from the series Still Growing Up Here, 2019, courtesy of the artist.

The truth is, we are never really sure if we are OK in these situations. Pasadena resident Juan Rodríguez asked, “How safe am I in an area that has a lot of refineries?” It’s a question we don’t always have an answer to. And that’s what fuels so much fear for residents in east and southeast Houston, home to so many petrochemical facilities.

In contrast, his work also explores the perseverance of these communities, many of which are intergenerational, with families moving to cheaper areas to raise families. Amidst the turmoil of industry-induced contamination, life still occurs; families still grow; and communities remain.

The artists in the exhibition are from different parts of the world, but they share an overlap in their experience of climate change. Laura Napier, once based in Houston and now in Ann Arbor, has been in conversation with DeHoyos Sauder since 2018 and will be exhibiting a film that identifies visual markers of pollution in different areas.

“Her work broadened my understanding of how oil is with us in every part of our everyday life,” DeHoyos Sauder said.

DeHoyos Sauder grew up in the Greater Houston Area connected to these communities surrounded by industry. While the impact may be clear, the connection is complex, with so many livelihoods in these communities tied to the same industries polluting them.

“The industry is so complex, and when we start thinking about ways to move forward, we have to consider how to unravel these complexities,” she stated. “Everyone knows there are causes and effects, but it wasn’t until they caught fire that people started paying attention to the why, how, and what remediation might look like.”

Remediation is an aspect that DiverseWorks itself is exploring, building methods on ways to work that center climate justice and action in the activities of the organization.

To craft a future without fear of devastating climate events, these steps are small on the grander scale but show an example of accountability that organizations and individuals can consider.

“There are possible creative solutions,” she reflected. “We don’t have to go into the world fearful of what’s going to happen in the next 30 years.”

—MICHAEL McFADDEN