There’s an old adage about how those who don’t remember history are doomed to repeat it, but histories are constructed through the perspective of those in power. When they don’t want you to remember something, it disappears from textbooks and lesson plans. And if they aren’t, people can construct their own version of events simply enough. This often results in history being less cyclical or repetitive than we might believe it to be. Parting the curtain may reveal we’ve been stuck in the same place for a long time. The curtains may change, but the problems rarely do.

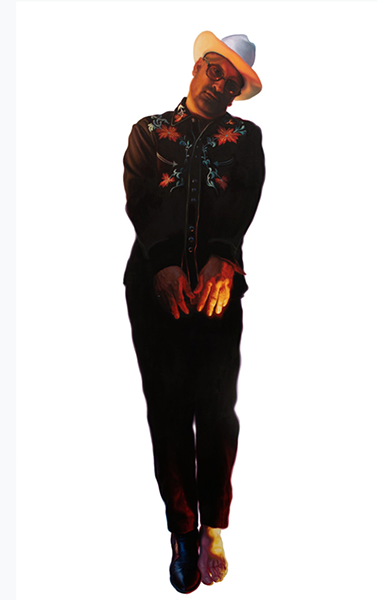

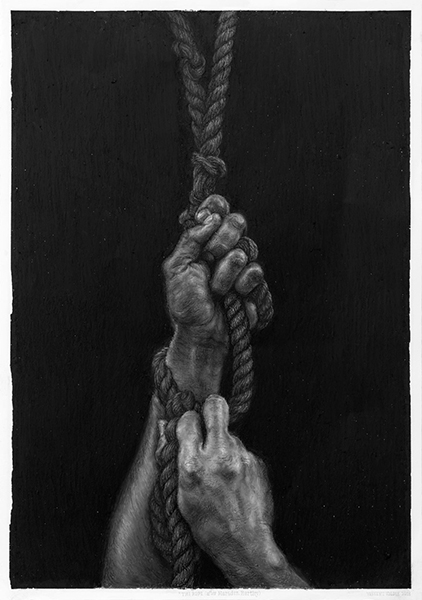

“The first time I remember encountering his work was at a now-defunct art fair. David Shelton Gallery was presenting The Strangest Fruit,” Restrepo recalled. “Encountering these haunting memories within the commercialized environment of the fair was bizarre, unexpected, yet impactful.”

In her first encounter with Valdez’s work, she found the pieces to be contemporary specters beckoning for attention, speaking from the past. Restrepo found herself taken with the resonance between the personal nature of the work and the political and conceptual considerations as Valdez depicted friends and family as stand-ins for historic figures who faced tragic ends.

Erasure, hidden histories, and the gap between past and present are often central to Valdez’s practice. The denial of history often on display in the world allows the bad to sink into the background, just below the surface and out of sight enough to be out of mind. Valdez creates counter-images, often centering people of importance in his own eyes, which encourage viewers to consider otherwise, that the problems of the past are more modern than they’d like to believe.

“There are very overt ways that Vincent celebrates the everyday and personal nature of his relationships, but he expands the idea of what is personal,” Restrepo said. “These histories resonate with him and urge him to continue his lifelong quest against erasure.”

1 ⁄6

Vincent Valdez, Eaten, 2018-19. Oil on canvas, Collection David Hoberman, promised gift to the Hammer Museum. Photo: Paul Salveson

2 ⁄6

Vincent Valdez, People of the Sun (Grandma and Grandpa Santana), 2018. Oil on canvas. Collection Alexa Pooter Brundage. Photo: Peter Molick.

3 ⁄6

Vincent Valdez, The Strangest Fruit (3), 2013. Oil on canvas. Collection David Hoberman. Photo: Mark Menjivar.

4 ⁄6

Vincent Valdez, The Rope, (After Marsden Hartley), 2018. Oil pastel on paper. Collection Lisa Rich and John McLaughlin. Photo: Peter Molick.

5 ⁄6

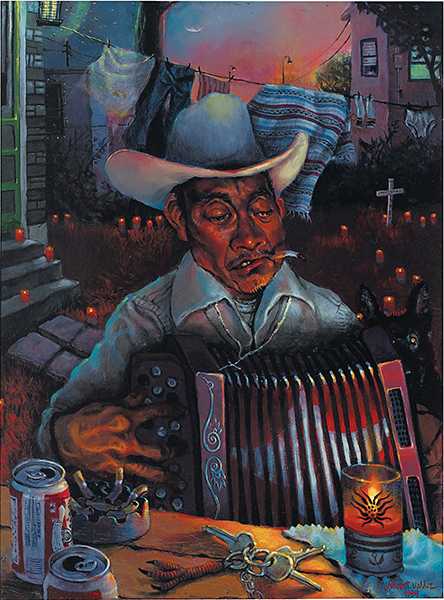

Vincent Valdez, Recuerdo, 1999, Oil on board. Courtesy Joe A. Diaz.

6 ⁄6

Vincent Valdez, So Long, Mary Ann, 2019. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Photo: Paul Salveson.

“Something I want viewers to take away is that his body of work resists type categorization,” Restrepo stated. “He’s playing with expressing new understandings of what being an American might look like, and I hope people recognize the invitation he’s extending to the viewer, correcting erasure and asking people to unpack them and fill in voids.”

Just a Dream… is an opportunity to explore over two decades of work that asks the viewer to look, look again, and look closely. A key example of this is El Chavez Ravine, a custom 1950s lowrider ice cream truck.

“You can’t take in the work at once because every inch is covered in paint, requiring eye movement, active looking, and physical movement,” Restrepo explained. “Vincent is more than a monumental, historic painter. The show will contain multiple mediums he’s explored: a lowrider truck, drawing on bronze, video work, prints. Showing the breadth of his work shows that he’s grappling with the breadth of the United States—its histories, its peoples, its futures.”

“I think that the way Vincent merges his lived experience with art historical references, the way he ushers in materials, and the way he hones his practice make him a singular artist,” Restrepo explained. “Vincent has so much complexity and beauty to offer. He makes images about people for people.”

—MICHAEL McFADDEN