At some time or another through history, every European country has had its own period of artistic and cultural flourishment: France had its Belle Époque, Italy had its Renaissance, and Spain had its Siglo de Oro. The Netherlands had its own during the 17th century, which today is commonly considered the Dutch Golden Age. Renowned for shipbuilding, the country’s merchant fleet was unmatched, leading to dominance in the global trade economy. The Dutch East India and West India Companies were established, trading posts and colonies sprang up in the Americas, Southern Africa, and Asia, and the Netherlands was Europe’s richest country for nearly 100 years.

Many say that the Dutch Golden Age was the first age of globalization. Tobacco, tea, and tulips were among the exotic international imports that became the subjects of still lifes, while the country’s maritime dominance inspired countless paintings of ships and ports.

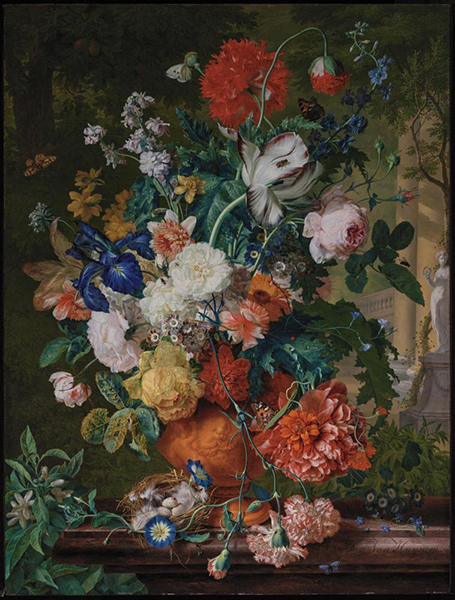

The exhibition’s opening section, The World at Home, introduces two examples of classic Dutch still life: Jacques de Gheyn II’s Vase of Flowers with a Curtain, positioned next to Jan van Huysum’s Flowers in a Terracotta Vase. Shackelford notes that the de Gheyn vase is brimming with tulips. “Tulips were a complete novelty at the end of the 16th century. They were first introduced in Europe from Asia Minor with Suleiman the Magnificent, who sent tulips as a diplomatic gift to the King of Holland. So, tulips, tulip mania, flowers – all of that – becomes an emblem in some ways of the internationalism of Dutch art.”

The section of Amsterdam as a Cosmopolitan Hub contains depictions of the port city through various works, including drawings and paintings by Jan van der Heyden, an intricately drawn map of the city, and a silver medallion from the stock exchange. “One of the really fascinating things about Holland was how many people from everywhere came to live there. The growth of Amsterdam across the 17th century quintuples in size….it became one of the great trading centers in the world” Shackelford says. “One of the Medici dukes goes to Amsterdam and writes that you can hear more languages being spoken in Amsterdam than anywhere else in Europe.”

The Dutch constitution in the 1580s guaranteed freedom of religion, which brought an influx of Jewish refugees from Catholic countries. “It’s really the first country in the world where it explicitly stated that you cannot be persecuted for your religious beliefs,” Shackelford says.

1 ⁄6

Willem Claesz Heda, Still Life with Tobacco, 1633, oil on panel, 20 x 29 3/4 in. (50.8 x 75.6 cm). Gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

2 ⁄6

Jan van Huysum, Flowers in a Terracotta Vase, 1730, oil on panel, 31 ½ x 24 in. (80 × 61 cm). Promised gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

3 ⁄6

Jacob van Ruisdael, Rough Sea, c. 1670, oil on canvas, 42 1/8 x 49 1/2 in. (107 x 125.8 cm). William Francis Warden Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

4 ⁄6

Rembrandt, Portrait of Aeltje Uylenburgh, 1632, oil on panel, 29 x 21 15/16 in. (73.7 x 55.8 cm). Promised gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

5 ⁄6

Nicolaes de Grebber, Tazza with the Four Seasons, 1606, silver-gilt, 5 7/8 × 7 5/16 in. (14.9 x 18.6 cm). Gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in honor of Thomas S. Michie, and in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

6 ⁄6

Gerrit Dou, Dog at Rest, 1650, oil on panel, 6 ½ x 8 ½ in. (16.5 x 21.6 cm). Promised gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Visitors will also have the opportunity to see an exquisite pair of silver Torah finials, the oldest known pair from the Netherlands. Shackelford chose to include them to convey how faith and tolerance were a hallmark of the Netherlands in the 17th century.

A collection of portraits in Global Citizens gives insight into the socioeconomic diversity of the Dutch. Frans Hals’ Cunera van Baersdorp shows an assertive looking woman in a dress of black silk, presumably imported and very expensive. A rare self-portrait of a female by artist Maria Schalcken can be found here, not far from one of Rembrandt and his wife, Saskia, jokingly referred to by Shackelford as the equivalent of a 17th century selfie.

Pride of their homeland is evident through Celebrating the Familiar, wherein a collection of drawings and paintings portraying the landscape and terrain characteristic of the Low Countries is displayed. Hendrick Avercamp’s Winter Landscape near a Village portrays a scene of people engaging in outdoor winter activities, from ice skating, ice hockey, and even ice fishing. “It’s really a sort of wonderful compendium of bits of history and bits of daily life, completely made up, of course, but reflecting something that actually could well have happened,” Shackelford notes.

The final three paintings Shackelford has chosen to conclude the exhibition were not in the original proposal, but he wanted to end it with a sense of optimism by displaying portraits of children. Jan Anthonisz van Ravesteyn’s Double Portrait of Jacquelin and Henrica Brouart features two richly dressed young girls holding cherries, symbols of charity. The stately black and white marble floor on which they stand implies that they are upper class. Shackelford notes that the children represent the generation that would inherit this world to take it into the next century. “This notion of both privilege, on the one hand, which you can scoff at,” he explains. “But also, these kids themselves are wholly innocent… they’re not yet part of the society, that global culture; they’re just born into it.”

—AMY BISHOP