Tavares Strachan wants to tell the story of the whole world. He wants an encyclopedia featuring Matthew Henson, the first Black man to visit the North Pole, as well as Robert Peary, a white man who accompanied him on the journey. He wants Black photographer Gordon Parks discussed as much as white photographer Ansel Adams. He wants Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey to appear alongside Napoleon Bonaparte.

Conceptual art is tricky for an audience to navigate, for a curator to stage and for an artist to justify. It can easily flop if the latter two can’t wrap their heads around a museum show. Is the artist grifting the viewer by applying layers of meaning with little attention to form, material and references? Will docents understand?

Strachan’s choice of material brings his broad themes together, and Hannah Klemm, Blanton’s curator of modern and contemporary art, brings his sprawling, complex work together.

Klemm, like Strachan, is a pro at making conceptual art accessible. The encyclopedia becomes a springboard to showcase his work, which includes a site-specific work layered with biographical references and a surprise display in the European galleries.

In the Contemporary Project Gallery surrounded by a field of dried rice is a sculpture of his grandmother built in “stacks,” much like what he declines to call totem poles. (He did not feel comfortable appropriating a practice unrelated to his Afro-Caribbean and American backgrounds.)

She carried vessels filled with food like fruit or rice on her head. “For him, the stack became this kind of symbol, both of that way of moving things around as a form of transportation,” said Klemm. “His grandmother used to say whenever she was carrying something and walking through town or moving through somewhere, it became an extension of her, an extension of her head, her thought process.”

1 ⁄7

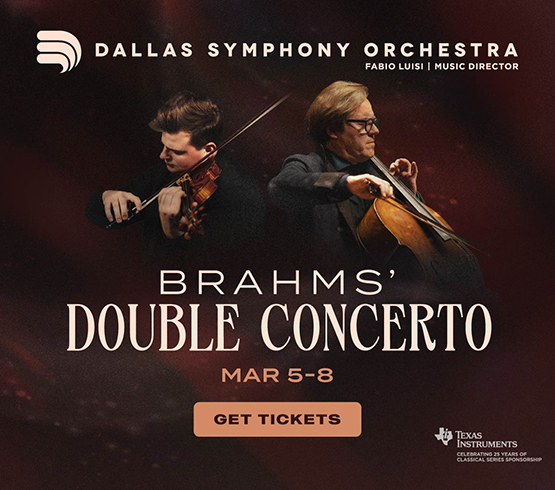

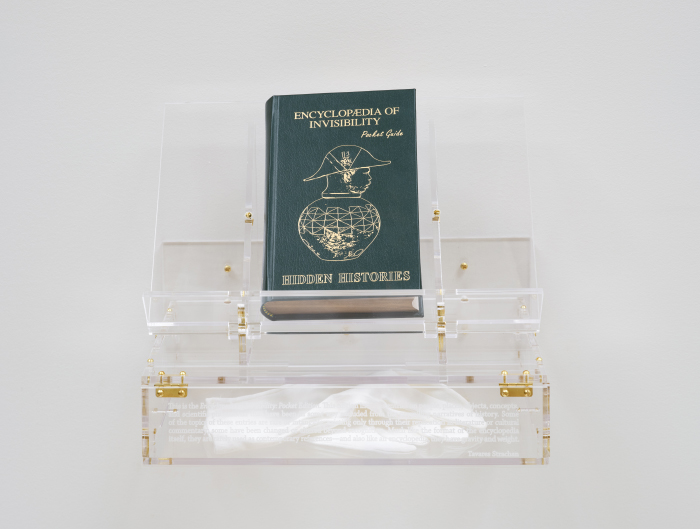

Tavares Strachan, Encyclopedia of Invisibility (Pocket Guide), 2024, leather, gilding, archival paper, lucite box and stand, overall: 9 1/4 x 12 1/8 x 10 in., edition of 250, courtesy of the Artist and Marian Goodman Gallery (photo: Elon Schoenolz)

2 ⁄7

Tavares Strachan, Black Madonna (Alice "Mamcethe" Biko and Stephen Biko) Gold, 2022, bronze, gold leaf, 31 1/2 x 10 5/8 x 8 5/8 in., edition of 3 plus 1 artist's proof (#1/3), courtesy of the Artist and Perrotin (photo: © Jonty Wilde)

3 ⁄7

Installation view of Tavares Strachan, Black Madonna (Louise Little and Malcolm X), 2022 at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

4 ⁄7

Installation view of Tavares Strachan, Black Madonna (Kadiatou Diallo and Amadou Diallo), 2022 at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

5 ⁄7

Tavares Strachan, Encyclopedia of Invisibility (Pocket Guide), 2024, leather, gilding, archival paper, lucite box and stand, overall: 9 1/4 x 12 1/8 x 10 in., edition of 250, courtesy of the Artist and Marian Goodman Gallery (photo: Elon Schoenolz)

6 7

Visitor in Tavares Strachan: Between Me and You at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, November 9, 2024–June 1, 2025

7 ⁄7

Installation view of Tavares Strachan: Between Me and You at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, November 9, 2024–June 1, 2025

“These are things that connect people, but that also have distinctive cultural frameworks,” Klemm said. “He’s really thinking about how we can consider ourselves more connected and more similar than disconnected and dissimilar. He’s taken that to an extremely metaphoric place and thinks of the stacks as a non-linear set of influences and thought processes that go into what he does.”

As for his grandmother, each stack references someone from history: the head of Marcus Garvey, a regular figure in his work, a basketball, a kettlebell, and musical notations.

“Each object is pulled from the encyclopedia or his own influences and interests. And then it’s stacked kind of the way thinking about stacking things and moving things through space on one’s head,” she said.

In Telluride, he built a similar neon installation: “WE ARE IN THIS TOGETHER.”

Positive, right?

Klemm suggested maybe not.

“In the sense that we are all in it together, it could be for good or for bad. And that can also be very bad. Belonging doesn’t always mean a fun belonging. It can be a violent or difficult sense of belonging,” she said.

He also makes a surprise appearance in the European galleries. Three sculptures from his Black Madonna series are reconsiderations of the common symbol in Christian art known as the Pietà, in which Mary holds the dead body of her son Jesus. He’s replaced Mary, the Madonna, and Jesus’ body with Black men from history who had been violently murdered.

The sprawling references to history and themes as seen in the show just how he thinks. “He’s one of those artists that likes things that come to him out of thin air where I’d have to read a hundred books and try to understand everything. Something will spark and he’ll just run with it,” she said.

—JAMES RUSSELL