Swimming pools, tennis courts, a bridge, an arch, her daughter’s toy blocks are all recurring images in Iranian-born artist Farima Fooladi’s paintings and installations. They are traces of her memories that exist somewhere between the real and the imagined, traveling freely between past and present, in a rich, layered visual space between two worlds, one the post-Revolutionary Iran where Fooladi grew up and the other her current home in Houston, Texas.

Painting helps Fooladi get away from the dissonance of the outside world and the politics that always follows her as an Iranian. The canvas is her safe place. “These places I’m painting are the same places I would actually go to when I was living in Iran,” says Fooladi.

She credits her father with her enduring interest in architecture. “My father was a civil engineer and instead of taking us to playgrounds, he would drive us a long way to abandoned historical sites.” Growing up, these historical monuments, crumbling arches, and ruins of 2000-year-old buildings were her playground. The sense of displacement that every immigrant experiences comes in part from the loss of physical access to these familiar places from home. “I’m playing with the memory of it,” says Fooladi. “If there is beauty in my paintings, it is in this act of preserving.”

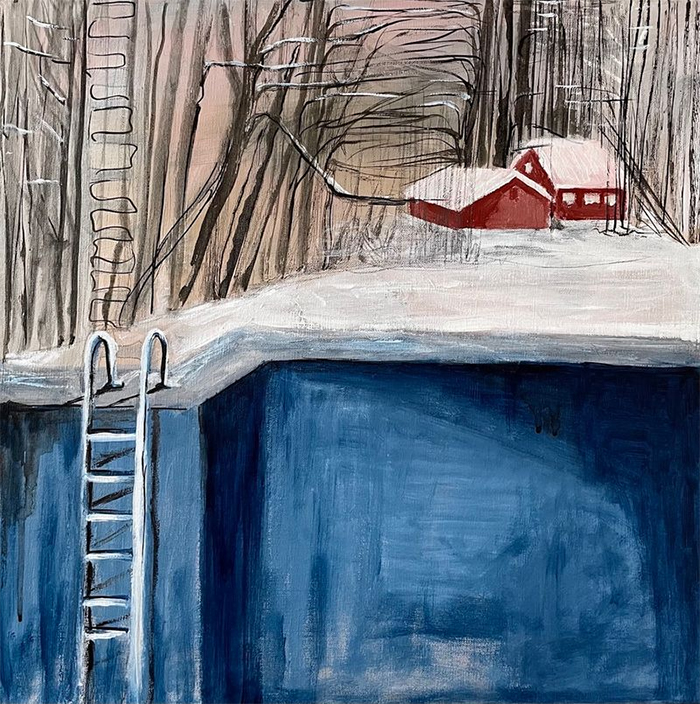

“That was my first memory of witnessing how architectural change from the outside can shape my own private environment” recalls Fooladi. These abandoned and repurposed swimming pools take on a surreal, confused presence in her paintings, often morphing into various irregular shapes and inhabiting fantastical landscapes.

A strong narrative impulse drives Fooladi’s art practice. Looking at her paintings is a cinematic experience. The viewer is immersed in the surroundings, every detail becomes vivid and almost tactile. She points to her paintings Of Curiosities and Road of Curiosity, and explains how she travels in her mind as she paints. “Here I’m taking a road trip in Iran and I’m thinking about what I would see. I want the viewer to have the feeling that they are sitting in a car looking outside as the scenery is changing.” Fooladi leans into the abstract and surreal, capturing something essential in the dark silhouette of a city, the luminous glow of brick factories, the odd swimming pools that don’t belong, traces of plant life, or the contours of mountains in the distance.

1 ⁄6

Farima Fooladi, I Myself In Summer Hours Wove Together Flowers, 20x24 inches, Mixed media on linen, 2025

2 ⁄6

Farima Fooladi, Both of Us Know The Dangers of This Depth, 20x20, Mixed media on linen, 2025

3 ⁄6

Farima Fooladi, Spring of Black Blooms, 39 x 51 inches, Mixed media on Linen, 2025

4 ⁄6

Farima Fooladi, Came For the View, 24 x 20 inches, Mixed media on linen, 2025

5 ⁄6

Farima Fooladi in her studio. Photo courtesy of the artist.

6 ⁄6

Farima Fooladi in her studio. Photo courtesy of the artist.

She likes to combine drawing techniques within her paintings. “I love the layers, drawing underneath painting, architectural rendering, and different types of mark making.” It all works together aesthetically. The fluidity of her thought process translates into a sense of movement within the layers of her paintings. “I like to travel within my paintings, at least in my thoughts.” She moves easily between pencil, graphite, charcoal, ink, and oil, using a variety of mediums to evoke different visual responses within one work. She compares it to the life of an immigrant like herself, always working with different languages in her head. Her palette comes from Persian paintings, old Persian books, and murals on architectural sites. “Those yellows, blues, and reds come back to me every time I choose colors,” she muses, “though I have become bolder with colors since I moved to the U.S.”

The immersive, tangible environments of Fooladi’s paintings are fully realized in her recent art installations. Her first foray into installation art was during her “Artists on Site” residency at Asia Society Texas Center in 2023. “I’ve always had ideas for installations but never had the resources, space, or funds to do it,” says Fooladi. Her swimming pool became truly immersive, as viewers found themselves standing inside to take in the surroundings from a new perspective. “I like building the space, and installation gave me that extra layer to come out of the two-dimensional world and really walk around and follow my thoughts.” From the pool, the viewer sees a rich assortment of images, a real ladder and painted ladders, streaks of deep blue water running down the walls, mountains and arches expanding beyond a painting on the floor, a scene within a scene shimmering at the vanishing point.

Fooladi creates ephemeral worlds from her personal memories, telling stories that explore the themes of migration, displacement, and transformation. Her spring solo show at Lawndale Art Center, Feb. 27 – May 3 will feature new works inspired by her recent MacDowell artist residency in wintry New Hampshire. There will be more swimming pools and tennis courts, familiar places in her imagination that connect her own past and present.

Growing up, her best friend’s father was an Asian gold-medal tennis player. She and her friend went to tennis school together until courts closed for women and girls. She stopped playing. Now her young daughter is taking tennis class in the Woodlands. One evening, as she watched her daughter play, she became mesmerized by all the balls going back and forth. “I saw the balls and all their shadows,” recalls Fooladi, “then my memories of tennis came back and I thought the tennis court was just like another swimming pool that got closed for some people. It was beautiful and serene, just the red and green court, the balls, and the trees in the Woodlands.”

—SHERRY CHENG