One of the profound joys of being a curator (and an arts writer) is discovering the work of an artist and, over the course of years, witnessing and supporting the development of their unique and uncompromising creative vision. For Christopher Blay, Director of Public Programs at the National Juneteenth Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and former Chief Curator of the Houston Museum of African American Culture, meeting Dallas-based artist David-Jeremiah and experiencing, in person, his 10-foot-tall assemblages of black and other polychromatic paintings on shaped wood, hung throughout a vast warehouse space, was inspiring, if a bit overwhelming, and would lead to his curating two exhibitions of the work.

Blay’s first exhibition at HMAAC in 2020 was an early career survey and solo exhibition of those works, some of which are included in The Fire This Time, on view Aug. 16-Nov. 2, 2025, at The Modern Museum of Fort Worth. Curated by Blay, the exhibition comprises four sets of seven paintings, the first three of which are in monochromatic black. “The last set of seven works in the show with color elements were all made in 2024 and have never been exhibited,” says Blay. Ten of David-Jeremiah’s earlier paintings will be installed in two circular arrangements in the galleries and will be the first time they have been exhibited as David-Jeremiah intended the works to be experienced.

1 ⁄4

David Jeremiah, The Fire This Time, on view Aug. 16-Nov. 2, 2025 at The Modern Museum of Fort Worth, installation image courtesy of the artist and The Modern.

2 ⁄4

Curator Christopher Blay, David Jeremiah, The Fire This Time, on view Aug. 16-Nov. 2, 2025 at The Modern Museum of Fort Worth, installation image courtesy of the artist and The Modern.

3 ⁄4

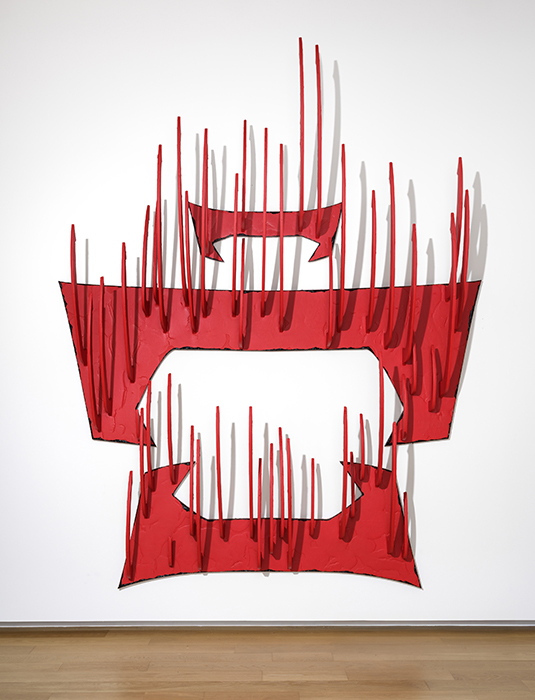

David Jeremiah, The Fire This Time, on view Aug. 16-Nov. 2, 2025 at The Modern Museum of Fort Worth, image courtesy of the artist.

4 ⁄4

David Jeremiah, The Fire This Time, on view Aug. 16-Nov. 2, 2025 at The Modern Museum of Fort Worth, image courtesy of the artist.

Pushing these paintings to the edge of conceptualism is David-Jeremiah’s description of the exhibit as “an inverted performance installation.” Over the relatively short span of his career, David-Jeremiah has used his body as artistic material, as in the 21-day endurance test The Lookout, where, within a gallery space-turned-cell block, visitors were invited to don a Ku Klux Klan hood and ink in a tattoo on David-Jeremiah’s left ribcage with a prison pick. In The Lookout, David-Jeremiah is using his body to define a conceptual space. In The Fire This Time, the paintings define that space and are as conceptual as they are physically imposing, and while an undercurrent of violence and power is palpable, there is also a feeling of ritualistic calm. “He’s thinking that instead of the work performing for the audience, the work makes the audience perform for it,” explains Blay. Like The Lookout, The Fire This Time is far from congenial, but without an audience, it is incomplete. In the last gallery of the exhibit, a final selection of seven paintings are suspended and installed in a round, like figures at a campfire, compelling the viewer to move into an empty, central space. In The Fire This Time, the “fire” is we, the audience.

—CHRIS BECKER