“I’m sort of a frustrated writer, in a sense,” Candace Hicks tells me over Zoom. “And so, making artist books is a way of self-publishing. It’s also a way of making things permanent.”

The project hits conceptual and aesthetic notes too. “Embroidering my emails into the cloth, making the whole thing out of cloth, created a sense that the text, image, and book weren’t separate,” she says. “They’re all integrated into one object. Whereas for me, with a printed book, I think of the book as an object and the text as an imaginary separate entity.”

1 ⁄6

Candace Hicks. Image courtesy the artist.

2 ⁄6

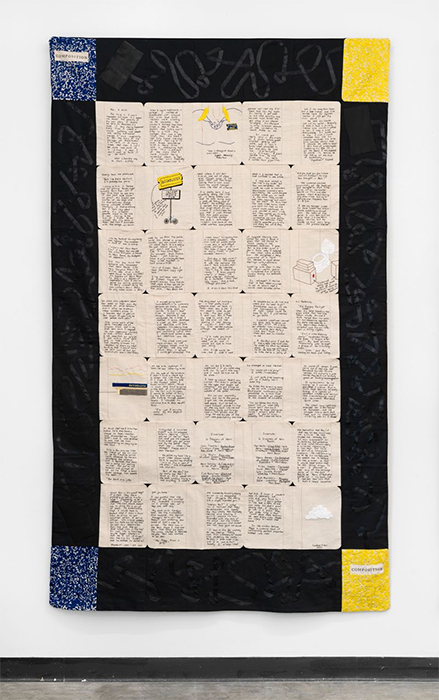

Candace Hicks, The Story I Tell at Parties, 2025, installation view. Image courtesy the artist.

3 ⁄6

Candace Hicks, Response to Sexual Harassment Report, 2024, embroidery on canvas. Image courtesy the artist.

4 ⁄6

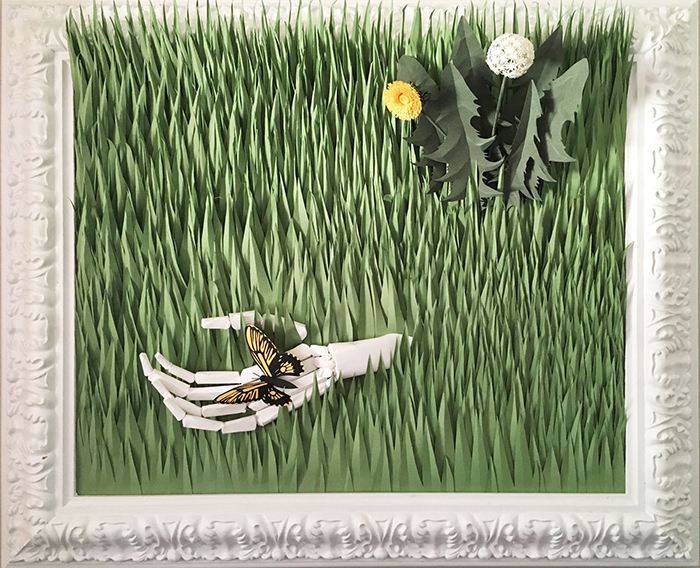

Candace Hicks, Many Mini Murder Scenes, 2018, mixed media diorama, 18 x 24 x 8 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

5 ⁄6

Candace Hicks, Many Mini Murder Scenes, 2018, cut paper, 22 x 30 x 3 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

6 ⁄6

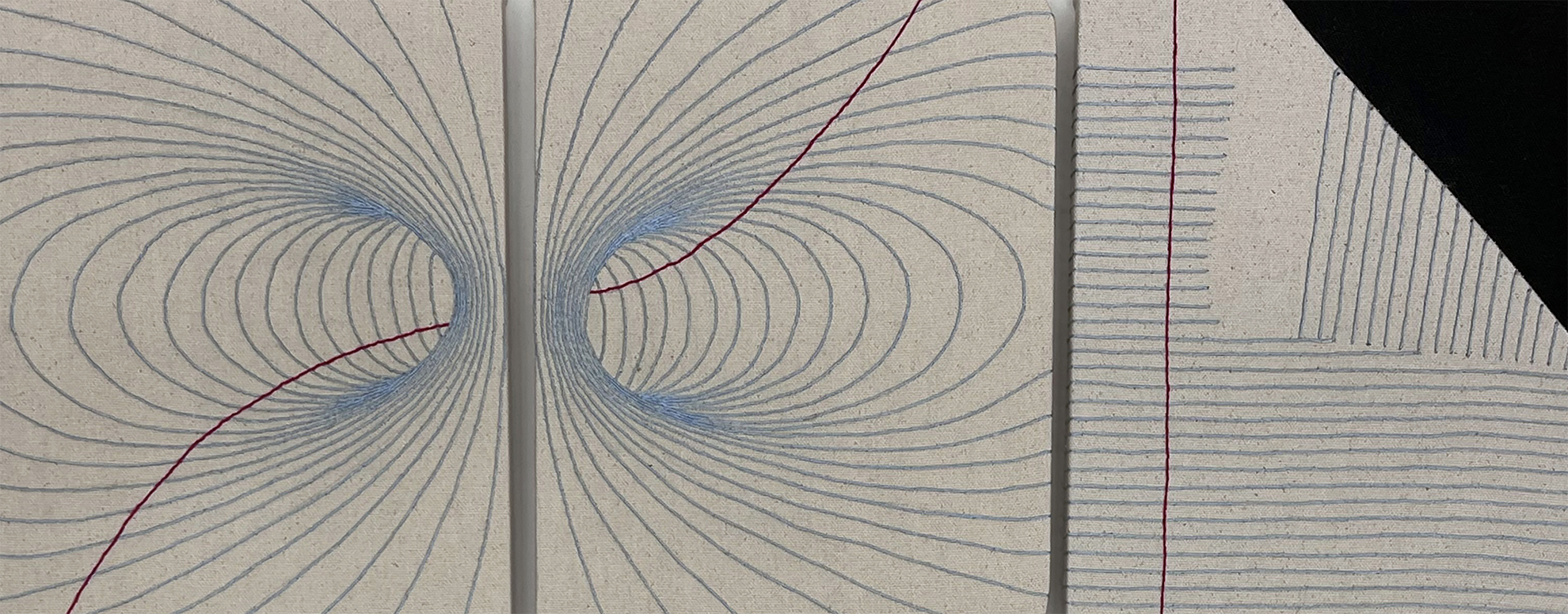

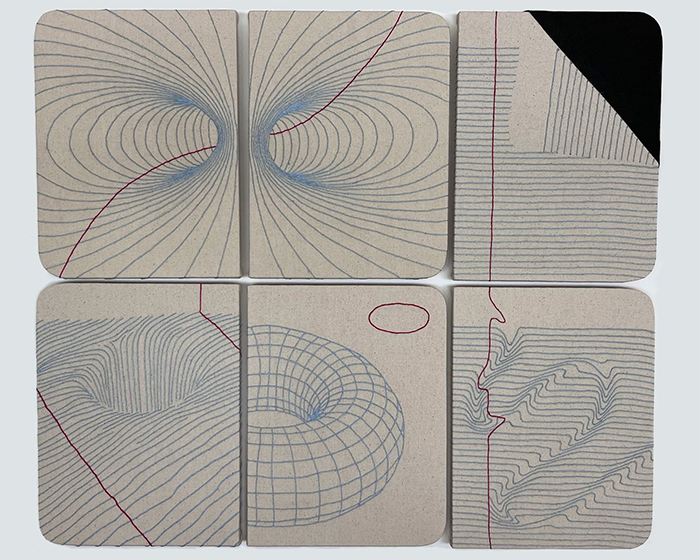

Candace Hicks, Notes for String Theory, embroidery on canvas, 2024, 8x10.5 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Hicks, who is currently an associate professor at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, earned her BFA at Austin college, studying drawing, painting, and French; she went on to earn her MFA in printmaking at Texas Christian University. She taught herself how to embroider during a case of world-changing-COVID-19-induced writer’s block. Embroidery wasn’t a family tradition; she didn’t have a family member who taught her how to embroider. She often jokes that her grandmother was an accountant.

“Embroidery, of course, comes with connotations of femininity, domesticity, and the notions of ‘women’s work,’” says Hicks. “It was a very practical thing for me to do because I was living in a small rural town, working as a secretary, where the artwork I could make needed to be portable and the materials had to be accessible. There wasn’t a chance of me being able to sit at my desk answering phones and painting on an easel, right?”

She adds that she liked that people knew what she was doing, but it was a “perfectly acceptable” activity.

Sanctioned reports, documented correspondence, and systemic changes are one attempt at permanence, storytelling is another. Hicks’s earlier series titled Many Mini Murder Scenes, which was on view at Women & Their Work in Austin, included tableaux of murder mystery novels: impeccable handmade miniature dioramas based on fictional murder mysteries, intricate paper construction compositions framed on the walls, and a wanna-be mystery sleuth’s dream of a guidebook that related to hidden texts. The show laid bare the construction of narrative, and the murder genre’s tendency toward misogyny and bias.

Earlier this year, Hicks’s solo exhibition The Story I Tell at Parties at Ivester Contemporary, also in Austin, featured three large wall-hanging quilts that tell and re-tell, misremembering and all, the story of her first job in the late 1990s, spelled out in hand-embroidered letters: she, a bike-riding, shaven-headed clerk at Blockbuster Video; he, her 15-year-old boss with gigantism who went missing; and they, supporting characters such as her co-workers, her roommate, frat guys, and the impending Y2K fiasco.

“When I first started doing embroidery, the end result had a sort of crudeness to it. Now it’s hard for me to recapture that because my embroidery has gotten more refined, almost by accident,” says Hicks. “And it’s a shame because those early books looked nuts, you know?”

Hicks likes working in a medium that’s not as valued culturally, and she wants to valorize things that are undervalued. She is currently collaborating with Sara-Jayne Parsons, Director and Curator of the Art Galleries at TCU, to curate Texere, an international, multilingual group textile exhibition that will debut at The Fort Worth Contemporary in spring 2027, travel throughout the US, and then return to France.

As for her Fulbright residency research, Hicks plans to delve deeper during her spring 2026 residency at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. So if you see her with a needle and thread in hand, look closely. What she’s making might just change your perspective.

—NANCY ZASTUDIL