The canvas can be a site where architecture tries to remember itself and fails on purpose. Planes hinge and collide. Edges behave like thresholds. Color reads as structure before it reads as atmosphere, and the eye keeps searching for a room, a landscape, a corner, something it can settle into, only to find the image withholding that comfort. Such work holds a steady tension between reference and refusal, where illusion never becomes a scene and abstraction never becomes pure. In that suspense, Rubén Guerrero makes painting look like a problem you can stand in front of, and time becomes part of the medium: you watch the image change because your perspective changes.

“Because we are a university museum, the educational component was essential,” curator Patricia Manzano Rodríguez explained. “It’s not only that we get to exhibit this person’s work in the U.S.—they also get a real opportunity to shape the work and thinking of our MFA students.” Past participants have used the program’s talks and studio visits as a point of contact with SMU students, and Manzano Rodríguez described those visits as a highlight: an encounter with “somebody who’s dedicated their life to art,” and proof, in real time, that an artistic career can expand across borders.

Guerrero, born in 1976 in Seville, arrives in Dallas with a practice that resists fixed labels while remaining unusually consistent in its commitments. Manzano Rodríguez emphasized that steadiness as one of his defining qualities.

1 ⁄4

Rubén Guerrero in his studio. Photo by Oscar Romero, courtesy of Galería Luis Adelantado.

2 ⁄4

Rubén Guerrero in his studio. Photo by Oscar Romero, courtesy of Galería Luis Adelantado.

3 ⁄4

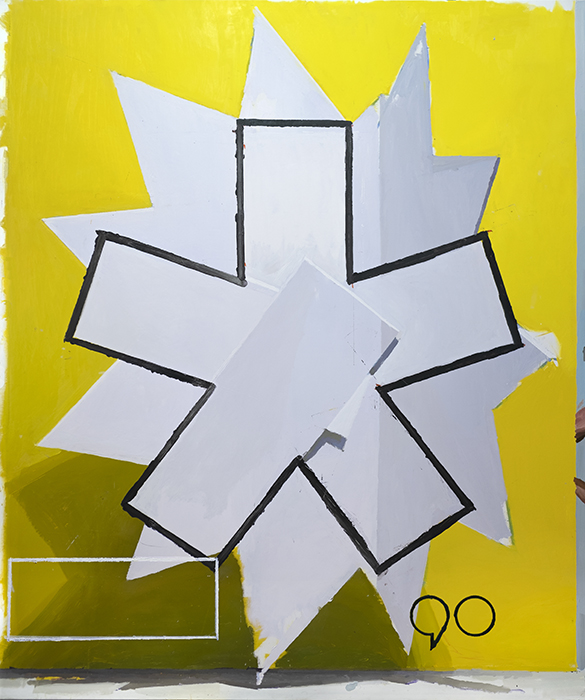

Rubén Guerrero (Spanish, b. 1976), Motif étoile (Star Motif ), 2024. Oil on canvas, 92 7/8 x 76 7/8 in. (235 x 195 cm). Photo: Pablo Asenjo, courtesy of Galería Luis Adelantado.

4 ⁄4

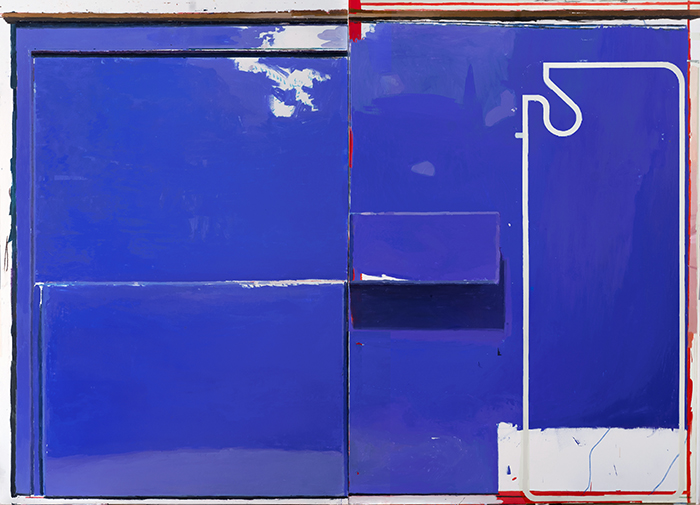

Rubén Guerrero (Spanish, b. 1976), S-t (primero y segundo) (S-T [First and Second]), 2023. Oil on canvas, 113 3/8 x 156 1/8 in. (288 x 396.5 cm). Photo: Pablo Asenjo, courtesy of Galería Luis Adelantado.

“He’s not a trendy painter at all,” she said. “He’s remained very faithful to his style, regardless of contemporary artistic trends.” Even so, the work does not read as static. Guerrero’s paintings press at the limits of what a flat plane can convincingly hold. In photographs, the paintings can already look strangely dimensional; in person, that effect becomes almost physical. As Manzano Rodríguez recalled from visiting his work in Spain, “We could not believe that what we were seeing was oil on canvas, that what we were seeing was a flat surface.”

Part of that volumetric charge sits in Guerrero’s relationship to Seville itself. Manzano Rodríguez connected his visual intelligence to the city’s history of painting. Guerrero, she noted, grew up surrounded by the legacy of artists such as Velázquez, Zurbarán, and Murillo, absorbing their lessons about texture, drapery, and embodied form.

“He says that he grew up looking at these artists in the museum and seeing how they played with volume and texture,” she said. “You can really see that influence in his work, obviously in a very different way.” What the Baroque achieves through illusionistic bodies and light, Guerrero reroutes through geometry and color, letting the painting carry depth as a kind of argument rather than a depiction.

His studio process also builds that argument from the ground up. Guerrero constructs small maquettes from cardboard and found materials, then isolates fragments from those structures as source material, an off-canvas architecture that later returns as painted structure. Manzano Rodríguez described the method as “very manual,” and part of what the public rarely sees. What viewers do see is the translation: planes that feel cut, propped, stacked, or swung into place; forms that hint at interiors or facades and then retreat back into painted fact.

“It suddenly becomes the longest minute in your life,” she said, and that discomfort becomes instructive. With abstraction, she added, duration changes perception. “The more you look at it, the more you’re going to see,” and what first appears plain begins to disclose decisions, adjustments, and quiet shifts. Guerrero’s paintings reward that kind of looking because they never lock into a single reading; they keep offering almost-images without allowing any of them to fully resolve.

The placement of the exhibition within the Meadows’ larger narrative of Spanish art sharpens that experience. Guerrero’s gallery sits as the culmination of a chronological path that moves from medieval and Renaissance works through Baroque, the nineteenth century, and modernism, ending in the present.

Manzano Rodríguez hopes visitors leave with something unresolved. “I hope they’ll walk away with questions,” she said. “It’s the kind of art that you might not understand, but it might make you question something.”

That “something” can be as basic as what belongs in a museum, or as personal as what the act of looking does to you when you slow down long enough to notice yourself doing it. Guerrero’s paintings do not offer a narrative to consume; they offer a situation to inhabit. They ask for a minute, then another minute, and in that extended attention they begin to feel less like images than spaces where perception rehearses its own limits.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN