Houston has a way of turning scale into a language. Freeways braid the horizon. Warehouses become studios. A single block can hold a theater, a brewery, a painter’s ladder, and a new kind of silence. At Sawyer Yards, that language speaks in industrial bones and white walls, and in spring 2026 it will speak in pictures, hundreds upon hundreds of them, drawn from four decades of FotoFest’s insistence that photography can be both evidence and dream.

“It’s the 40th anniversary of the biennials specifically,” Evans said, and that distinction matters because the Biennial has always been FotoFest’s loudest civic gesture: a recurring moment when the city’s ordinary surfaces, museum walls, gallery partitions, lobbies, hallways, become conduits for other places, other histories, other ways of seeing.

The organization was founded and incorporated in 1984, co-founded by Watriss, Frederick Baldwin, and Houston gallerist Petra Benteler. The spark came through travel. Watriss received recognition for documentary work and, Evans said, “because of that she was able to travel. She and Fred were able to travel to Europe,” where they encountered Paris’s Mois de la Photo and the Rencontres d’Arles.

1 ⁄8

Lalla Essaydi

Morrocco, b. 1956

Converging Territories #24, 2004

Chromogenic prints

Courtesy of the artist

FotoFest Biennial 2014

View From Inside: Contemporary Arab Photography, Video and Mixed Media Art

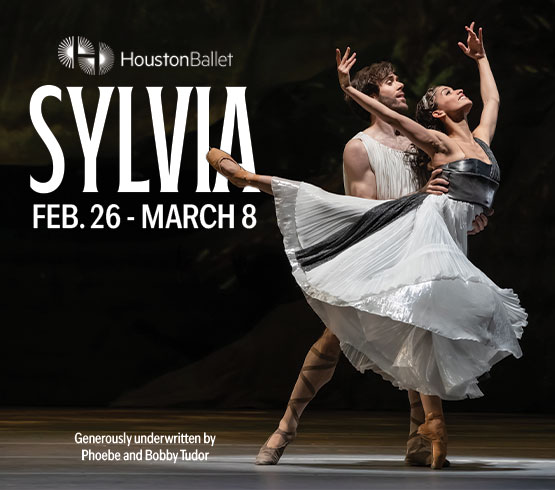

2 ⁄8

Flor Garduño

Mexico, b. 1957

La Mujer, Juchitán, 1987

Gelatin silver print

From Witnesses of Time—LATIN AMERICA

Courtesy of the artist

FotoFest Biennial 1992

LATIN AMERICA AND EUROPE

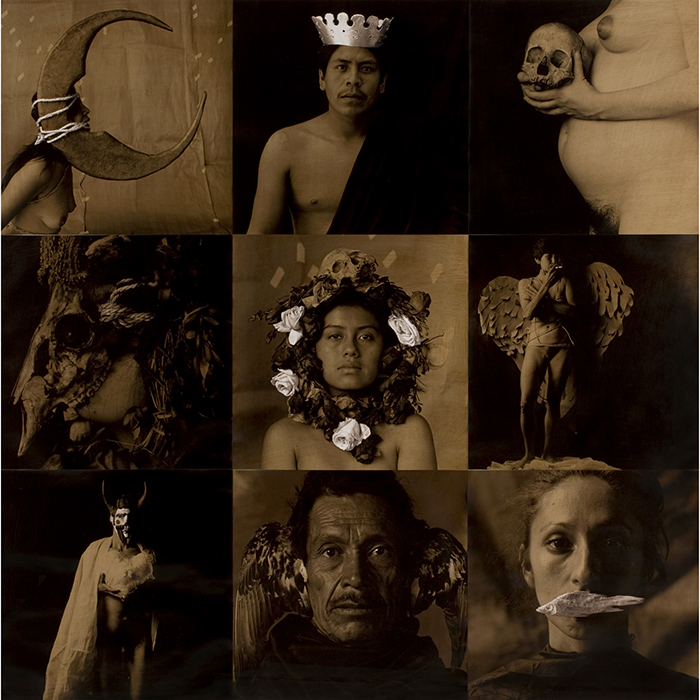

3 ⁄8

Luis González Palma

Guatemala, b. 1957

La Lotería [The Lottery], 1988–1991

Inkjet reproduction print

From Nupcias de soledad —LATIN AMERICA

Courtesy of the artist

Biennial 1992

LATIN AMERICA AND EUROPE

4 ⁄8

Alfredo Jaar

Chile / United States, b. 1956

From The Sound of Silence, 2006 - Video Animation Still

Inkjet reproduction print

From Artists Responding to Violence

Courtesy of the artist

FotoFest Biennial 2006

The Earth & Artists Responding to Violence

5 ⁄8

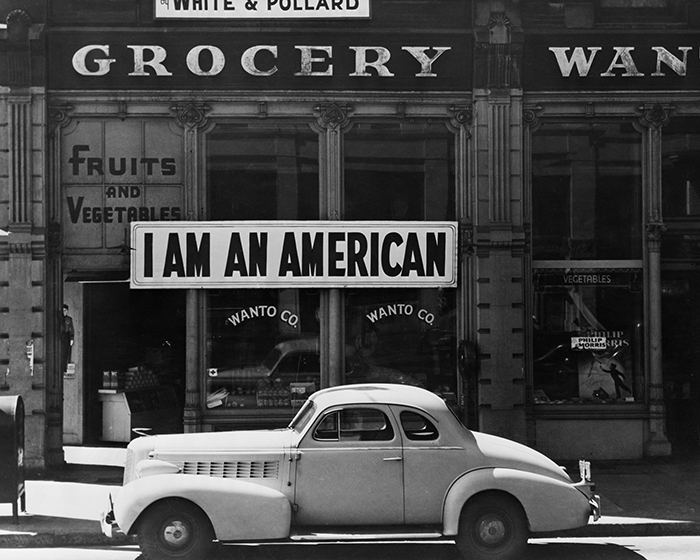

Dorothea Lange, United States, 1895-1965

“Oakland, CA, March 1942 – A large sign reading, ‘I am an American’ placed in the window of a store in Downtown Oakland on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to vacate from West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be relocated with hundreds of Japanese-Americans to a War Relocation Authority center,” 1942

Inkjet reproduction print

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC

FotoFest Biennial 2022

If Had a Hammer

6 ⁄8

Martina Lopez

United States, b. 1962

Heirs come to pass, 2, 1991

Inkjet reproduction print

Courtesy of the artist

FotoFest Biennial 1994

AMERICAN VOICES: Latino Photography in the U.S

Mexican American Artists

7 ⁄8

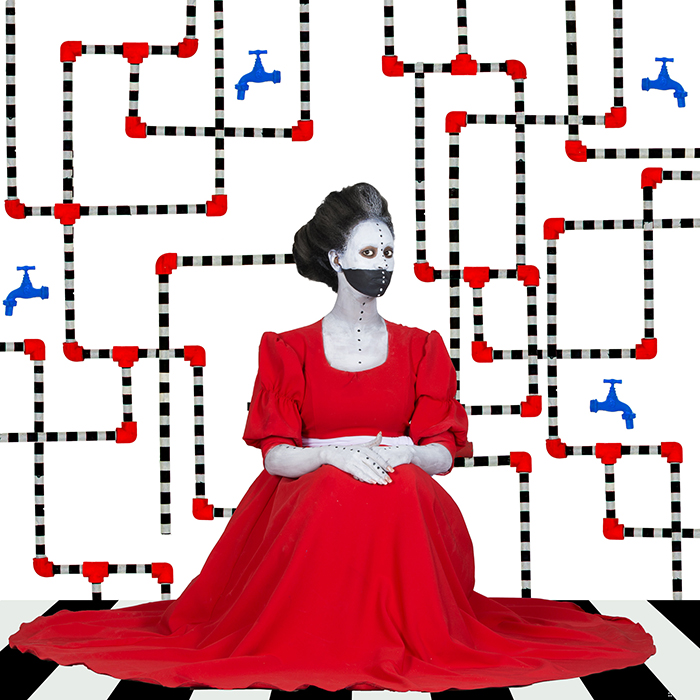

Aida Muluneh

Ethiopia, b. 1974

Access, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

From the series Water Life, 2018

Inkjet reproduction print

Commissioned by Water Aid, 2018

Courtesy of the artist

FotoFest Biennial 2020

African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other

8 ⁄8

Mónica Alcázar-Duarte

Mexico/ United Kingdom, b. 1977

Güerita, 2017

From the series Second Nature, 2017–Print on dibond (with subframe)

Courtesy of the Artist

FotoFest Biennial 2022

If Had a Hammer

Arles, Evans noted, “mobilize[s] spaces throughout the city to show photography,” a model that made Houston feel less like a peripheral site and more like an ideal host. “Houston needed this kind of thing,” he said, and the founders believed the city’s “entrepreneurial nature” and “can-do attitude” could support a festival that did not wait for legitimacy to arrive from elsewhere.

Evans described a phrase Baldwin returned to often, and it reads like a thesis for FotoFest itself: “One of, and perhaps the central idea around FotoFest is that it creates energy.” The word carries local resonance, energy as industry, energy as force, energy as catalyst, and it also describes what the biennials have done at their best: they have pulled institutions and audiences into motion, coaxing Houston into a citywide act of looking.

The first Biennial in 1986 arrived as a declaration of scale. “There were six museums, 14 art spaces, 27 commercial galleries and 17 corporate buildings that showed photography,” Evans said, with work “from 16 countries.” The first portfolio review unfolded at the Warwick Hotel (now Hotel ZaZa), and the festival made an immediate impression. But the most telling detail is not press coverage or attendance. It is the founders’ refusal to begin modestly. “Given Houston’s scale, they thought it should begin big,” Evans said. “Some people advise them to start small and build up and they were like, no… we want this to be a big thing.” In that first edition, Evans noted, “almost 800 photographers” showed work across the city, and the amount of exhibition surface became its own kind of urban marker: “There was like the equivalent of a mile of linear feet of wall that was taken up by photographs.”

That long arc, early breadth, later focus, forms the spine of Global Visions—FotoFest at 40. The 2026 Biennial does not simply commemorate past editions. It reconstructs them, pulling forward what Evans described as “many of the most significant exhibitions in the whole history of biennials.” The show, he said, will include “at least one project from each biennial and re-showing that work. It’s like a retrospective of FotoFest.”

—MICHAEL McFADDEN