Sometimes the drama of an artist’s life can overshadow the art itself. Case in point, Mexican Modernist painter Abraham Ángel, whose paintings are featured in almost every book or exhibition devoted to the period. Yet the beauty, complexity and creative vision of the actual artwork sometimes gets lost in the tragic story of Ángel’s early death at age 19 and the fact that only 20 of his paintings survive.

The exhibition’s curator, Dr. Mark A. Castro says he dreamed about organizing an Ángel exhibition for many years, and the DMA was quick to agree.

“What drew us was the immense quality of his paintings, which are incredibly compelling and moving. But they also often offer social commentary on the changes that are happening in Mexico from the perspective of a young person who is living in the capitol, who is queer, living with his partner in this kind of bohemian circle of friends,” says Castro.

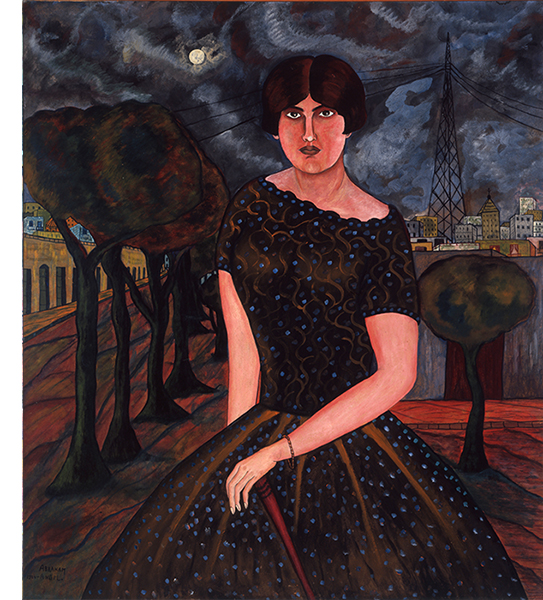

Castro uses the beguiling Portrait of Cristina Crespo as an example of Ángel’s ability to paint a character study amid a rich landscape while also using the images to depict the rapid social and cultural changes in Mexico after the Revolution. Crespo sits looking “boldly” at the viewer as both the powerful center of the painting and as an intersection between two distinct landscapes, one rural the other urban.

“He’s married who she is, this modern woman, with the change that is happening across Mexico at this moment,” explains Castro. “The country is modernizing. It is urbanizing at an incredible rate, especially in Mexico City. You’re seeing behind her this kind of transition from the past to the future, the old to the new.”

Castro notes that in choosing to paint a woman in this landscape, Ángel also might be making a point about the people who are influenced by this great societal movement, as well as those contributing to those changes.

1 ⁄6

Abraham Ángel, The Girl in the Window / La chica de la ventana, 1923, oil on cardboard, 51 1/8 x 47 1/4 in. Museo de Arte Moderno. INBAL / Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City.

2 ⁄6

Abraham Ángel, Portrait of Cristina Crespo / Retrato de Cristina Crespo, 1924, oil on cardboard, 53 7/8 x 47 5/8 in. Museo Nacional de Arte. INBAL / Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City.

3⁄ 6

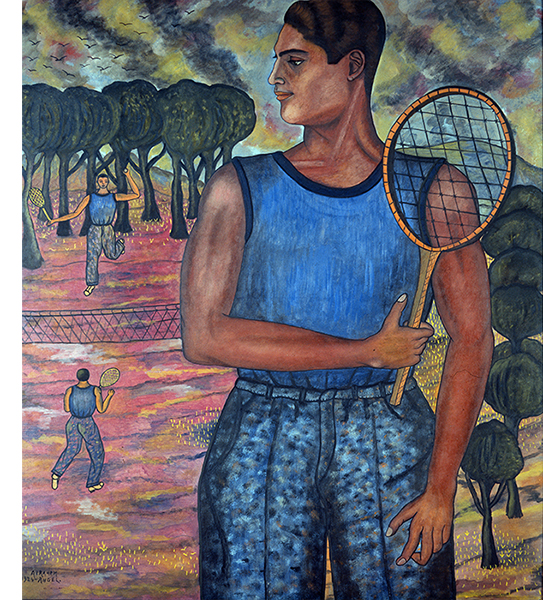

Abraham Ángel, Portrait of Hugo Tilghman / Retrato de Hugo Tilghman, 1924, oil on cardboard, 53 1/2 x 47 1/4 in. Museo Nacional de Arte. INBAL / Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City.

4 ⁄6

Abraham Ángel, Portrait of Manuel Rodríguez Lozano / Retrato de Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, 1922, varnished tempera on cardboard, 22 5/8 x 17 5/16 in. Museo de Aguascalientes. INBAL / Secretaría de Cultura.

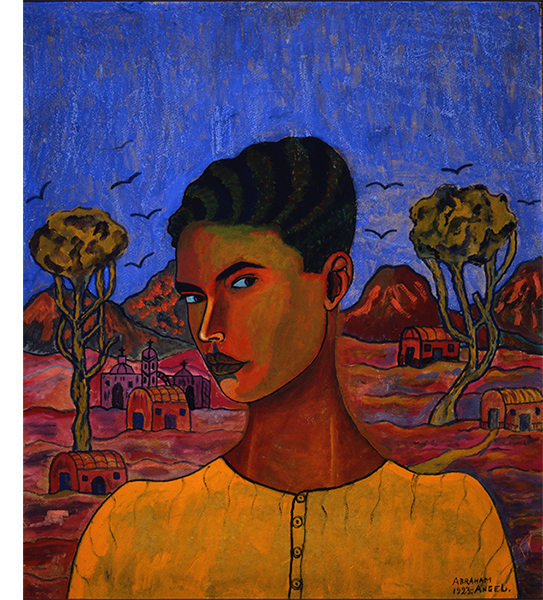

5 ⁄6

Abraham Ángel, Self-Portrait / Autorretrato, 1923, oil on cardboard, 31 7/8 x 28 1/4 in. Museo Nacional de Arte. INBAL / Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City.

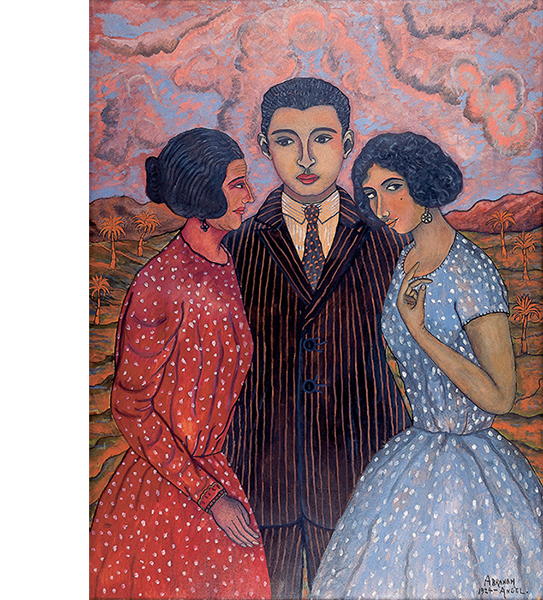

6 ⁄6

Abraham Ángel, The Family / La familia, 1924, oil on cardboard, 63 x 48 in. Museo de Arte Moderno. INBAL / Secretaría de Cultura, Mexico City.

I asked if Ángel used his art to make critical commentary on Mexican society or was he primarily observing and then depicting those changes around him. Castro says while not overtly political, Ángel likely made conscious choices in what and how he painted the world around him.

“By observing and turning those observations into works of art, I think he is offering commentary. I don’t believe him necessarily to have been a political painter with an agenda for this work; however, in choosing to paint what he chose to paint and doing the kind of work he chose to do, that evokes certain kinds of political agendas.”

“I would tell people to let the work do its magic on them because it will.”

And for those already seduced by the sorrow of Ángel’s life and death, Castro hopes the paintings themselves give us a new perspective on that story’s ending.

“I think it’s a great opportunity to punctuate that narrative and not let the end of his story be one of tragedy but instead be one of endurance. His work is still celebrated and still creating a sensation and attracting attention almost a hundred years after his death, that’s the legacy. The legacy for me is the work.”

—TARRA GAINES