In the attic of memory, objects slip out of time: A letter filed away, a photograph without a name, a clay koala bear made by a child and placed on a shelf. In Francesca Fuchs’s exhibition The Space Between Looking and Loving, on view at the Menil Collection through Nov. 2, 2025, these things become anchors. They do not simply mark the past, but extend it, open it, allow it to breathe.

Fuchs is known for her studies of domestic life, for paintings that elevate the overlooked objects that fill our shelves and shape our sense of self. But here, she brings a new dimension to that practice: a return to an origin point, a nexus of art, family, and place.

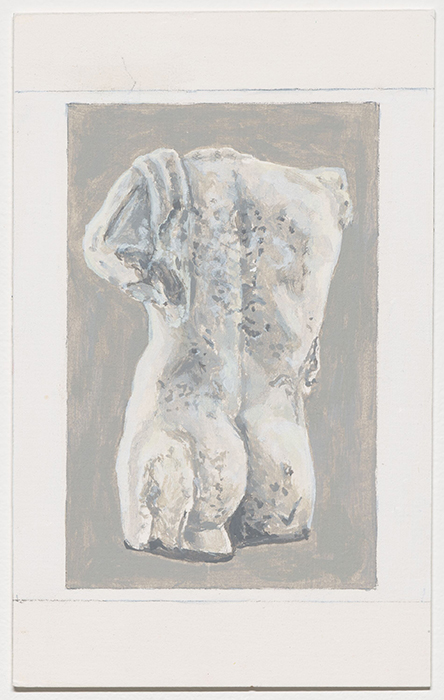

“It was an extraordinary touching across time,” she said. “A love triangle—between my father, the torso, and the people who made this museum.”

1 ⁄6

The Space Between Looking and Loving: Francesca Fuchs and the de Menil House, The Menil Collection, Main Building; installation image.

2 ⁄6

Francesca Fuchs, Male Torso (Back) Sketch, 2022. Acrylic on cotton rag, 8 × 5 in. (20.3 × 12.7 cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Francesca Fuchs. Photo: Thomas R. DuBrock

3 ⁄6

Francesca Fuchs, Double Matisse, 2024. Acrylic on canvas over wood panel, 46 1/2 × 34 1/2 in. (118.1 × 87.6 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Inman Gallery, Houston, and Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas. © Francesca Fuchs. Photo: Thomas R. DuBrock

4 ⁄6

Francesca Fuchs, Fleurs Coquillages, 2024. Acrylic on canvas over wood panel,17 5/16 × 22 in. (44 × 55.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Inman Gallery, Houston, and Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas

5 ⁄6

Francesca Fuchs, Owl, ca. 1974. Ceramic and glaze, 8 1/2 × 4 1/4 in. (21.6 × 10.8 cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Francesca Fuchs. Photo: Thomas R. DuBrock

6 ⁄6

The Space Between Looking and Loving: Francesca Fuchs and the de Menil House, The Menil Collection, Main Building; installation image.

“Repetition and iterations are part of the work,” she explains. “Each time the investigation takes me closer to something I’m looking for.”

It’s not a straightforward exhibition, more a slowly building composition, each piece a note in a larger chord. Fuchs and Menil curator Paul R. Davis met weekly at Black Hole Coffee House for months, selecting works from the Menil’s collection and from the de Menil house itself to place in conversation with her own. The result is a kind of living archive where her paintings, institutional ephemera, and found photographs commingle with museum objects and family keepsakes. What emerges is a meditation on how objects function not only as things we look at, but as things that look back.

“I think that objects accumulate histories,” Fuchs said. “I almost want to give objects personhood. They grow in power with our love and looking.” This is more than metaphor in her work, where looking becomes an act of care, and care becomes a form of attention so focused it borders on devotion.

That’s why The Space Between Looking and Loving feels less like walking through a gallery and more like being allowed inside someone’s home. There is an owl Fuchs made as a child in the 1970s, which hung in her parents’ house for years. There are small sculpted koala bears made of clay Fuchs dug from the soil in Germany, one of which sat for decades in her mother’s kitchen before accidentally dissolving during a well-intentioned cleaning. Her mother asked for a replacement. Fuchs made three, all of which are on display, with her mother’s choice elevated.

“I hope this story resonates with people,” Fuchs stated, “but I would never want to dictate what they experience. If you’re looking closely, there are a lot of rewards built into it.”

In many ways, the Menil Collection has always been about looking closely. It is a museum that resists spectacle. Its rooms breathe. Wall labels melt into the paint. The viewer is left alone with the work. For Fuchs, the Menil has always felt like home.

“It was like an extension of my living room,” she says. “To show this here, in this museum, is deeply emotional.”

Fuchs’s own home plays an essential role in her work. She paints what surrounds her: toys, art by friends, objects that would never appear in a museum but matter all the same.

“In a home, you’re living with artists who aren’t represented in museums or a reproduction,” she explained. “They can be equally important.”

The de Menil house, which she visited for the first time while working on the show, echoed that intimacy. A Philip Johnson structure softened by Charles James interiors, it felt to her like a “particular, intimate kind of living space,” an echo of her own approach.

Perhaps that is what The Space Between Looking and Loving reveals: that intimacy can be a method, a philosophy, even a politics.

In her hands, the archive is not static. It is living, shifting, full of emotional weight. The show may be anchored by an ancient Roman torso, but it ripples out across generations: a daughter sorting her father’s papers, a mother holding a new version of a lost bear, a city that connects them all through art.

Fuchs doesn’t claim final answers. “I’m sort of slow,” she laughed. “This experience will show itself as things move forward with me.” But something changed in the process of making this show. “Over time, I’ve become more comfortable revealing openly certain aspects,” she said. “This is a deeply personal show, and a real privilege to share it in such a beautiful public institution that’s free.”

What remains is the space between personal and public, past and present, memory and material. A torso, a photograph, a letter, a bear. Things we live with that also live with us.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN