Do an online search for Cowboy, the new exhibition on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art Sept. 28 – March 23 in Fort Worth, and those results will likely first yield links to Texas-born and raised superstar Beyoncé’s latest album, Cowboy Carter.

Yet this exhibition/album title overlap is more than a coincidence. It gets to the questions of history and identity the show poses and the complex responses the show’s artists make through their paintings, photography, sculptures, installations and multidisciplinary work.

“Artists from different communities are reconciling their identities with these traditional figures of the cowboy and trying to broaden the understanding of who the cowboy is or what a cowboy looks like. I think that’s definitely driving this exhibition, and I think it’s driving the work of artists in the visual and plastic arts and also artists in pop culture like Beyonce and Lil Nas X,” describes Carrión, when I asked about this synchronistic timing of the exhibition.

Originally organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, Cowboy includes over 60 late 20th century to 21st century artworks from 28 artists. The Carter will be the only other museum presenting the exhibition, and Carrión says it’s a good fit.

“The Carter has a long history of showing art of the American West. In our galleries, we have works that were created by artists like [Frederic] Remington and Charles Russell, artists of the old west and artist who contributed to the creation of the figure of the cowboy, as we traditionally understand it,” describes Carrión, adding that this new Cowboy exhibition “expands that understanding of the cowboy that our galleries support. It complements and expands the way in which we portray the American West.”

1 ⁄7

Gregg Deal (b. 1975), Teepugoobakwaetu Modu

(Animals That Roam On The Earth), 2023, performance, mixed media, installation view at MCA Denver, Courtesy the artist, Photo by Wes Magyar

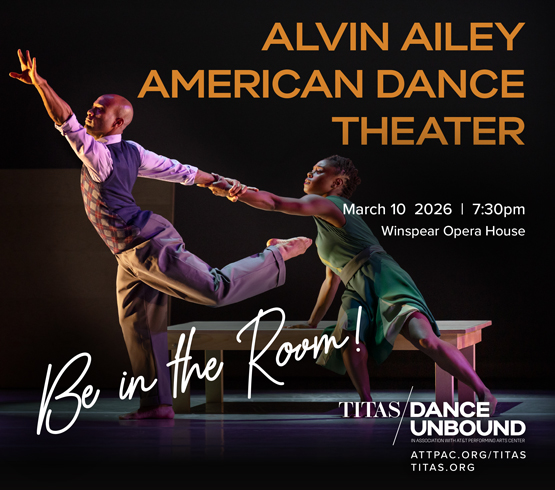

2 ⁄7

Akasha Rabut (b. 1981), Jesse Murdock, 2014, archival digital print mounted to matboard, Courtesy the artist

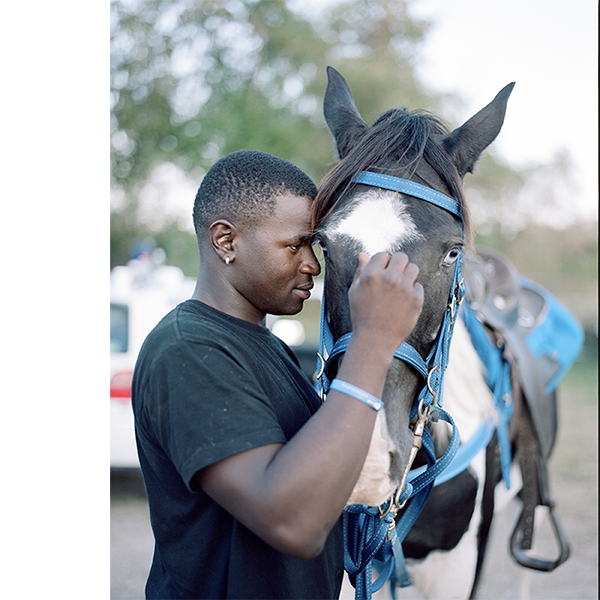

3⁄ 7

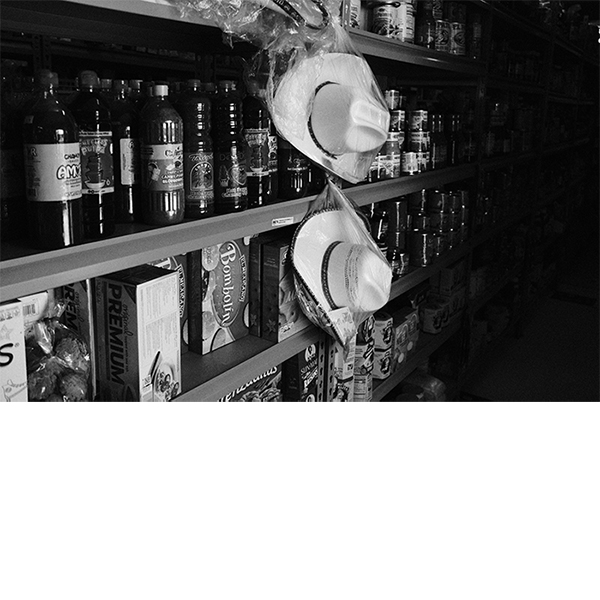

Juan Fuentes (b. 1990), Untitled, 2021, from the series Thirty-Six Miles East, photograph, Courtesy the artist, Photograph originally commissioned by the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art for Anythink Bennett

4 ⁄7

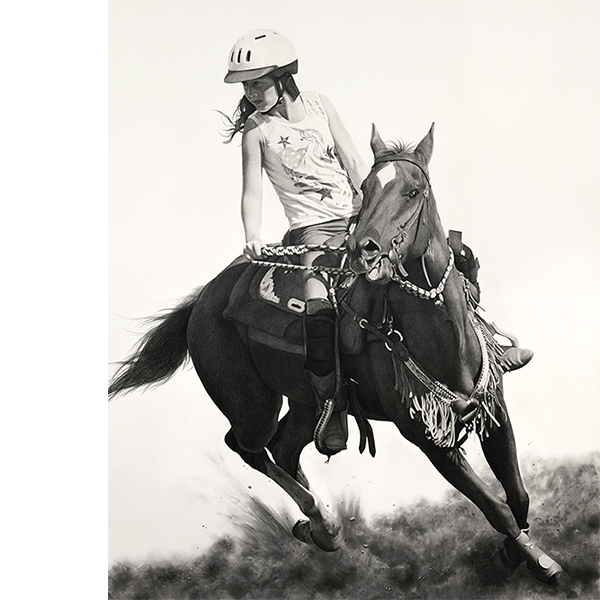

Karl Haendel (b. 1976), Rodeo 11, 2023, pencil and graphite on paper, Courtesy the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, and Wentrup Gallery, Berlin

5 ⁄7

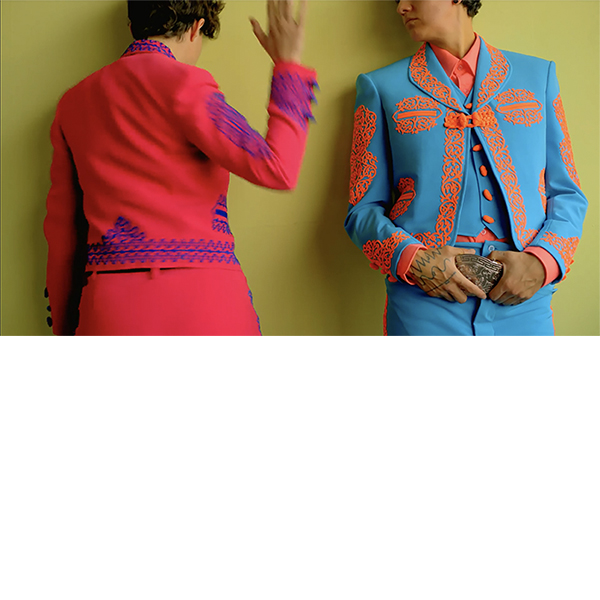

rafa esparza (b. 1981), in collaboration with Fabian Guerrero (b. 1988), Querías Norte, 2023, mixed media, four framed photographs, installation view at MCA Denver, Courtesy the artists, Photo by Wes Magyar

6 ⁄7

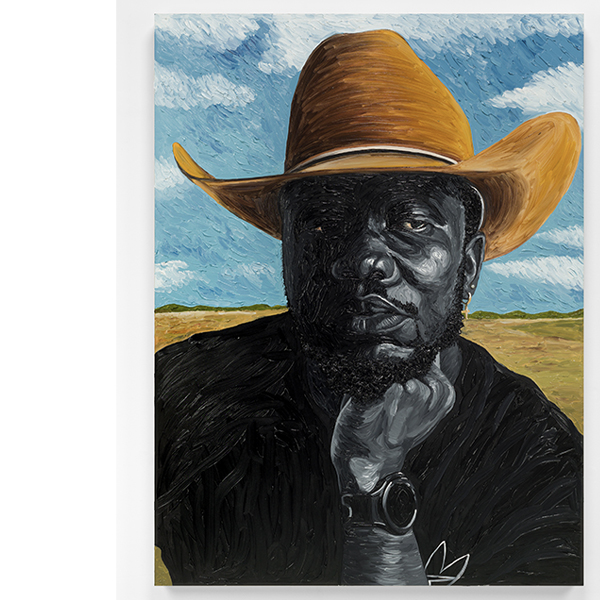

Otis Kwame Quaicoe (b. 1988), Caught in the Act, 2023, oil on wood panel, Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech, © Otis Kwame Quaicoe, Photo by Mario Gallucci

7 ⁄7

Ana Segovia (b. 1991), Aunque me espine la mano,

2018, video (5:34), Courtesy the artist

“The diversity has always been there, it’s just that artists did not choose to represent that before,” comments Carrión.

The exhibition showcases mostly contemporary artwork with a still from Andy Warhol’s 1965 short film Horse as one of the oldest pieces. Several works commissioned for the exhibition were completed within the last two years. One installation, Querías Norte, has its boots literally planted in today’s freshly made adobe floor.

Thematically, some of the artists gaze into the past, while others examine the enduring myth of the cowboy into the 21st century.

For a powerful example of an artist depicting the diverse faces of historical cowboys, Carrión cites Kenneth Tam’s two-channel video Silent Spikes. As the video references the history of 19th century Chinese workers who constructed the U.S. transcontinental railroad, it also explores stereotypes and myths of masculinity and individualism that decades of film and stories have built into the cowboy figure.

Another work that unearths and illustrates a largely forgotten western past is writer and artist R. Alan Brooks’s Cowboy-commissioned graphic novel, A Dream to Dearfield. Brooks puts the early 20th century history of the Black homesteader community of Dearfield, Colorado into graphic story form.

“She’s trying to bring attention to a part of history that it is not just the male cowboys who were responsible for taming the west,” explains Carrión, but notes a closer look at the painting might reveal an ambivalence to women’s share in that taming.

“I have come to think of ‘the west’ as a psychological space where ideas about freedom, identity, and land threaten to eliminate or warp real histories, perceptions of self, and our relationship to the world around us,” Kennison has stated about her current work.

“The show creates a more complex understanding of the cowboy, but I think it’s also just recognizing that it’s always been complex,” finds Carrión of these new, but perhaps more accurate, visions of the old west.

While these artworks depict the often forgotten faces of historical cowboys, other artists in the show examine how older generations of artists and institutions might have contributed to that forgetfulness. Photography work by Stephanie Syjuco seems to make such a point. Originally commissioned by the Carter for a solo exhibition in 2022. Syjuco’s Set-Up (The Broncho Buster 2) documented Carter staff as they prepped a Remington sculpture for display. In her photo, the sculpture almost disappears into the black backdrop, making the preparation the focus.

Still other pieces in the show are grounded very much in the here and now, even as the true and mythologized images of the cowboy dance alongside the contemporary cowboy.

For the installation, Querías Norte, a multi-layered multidisciplinary collaboration between rafa esparza and Texas-born artist Fabian Guerrero, the Carter is laying a real adobe floor in one of the galleries. As the floor dries, two men will dance together, leaving their footprints and two pairs of empty boots as an earthly record of their dance. The installation will also include paintings by esparza of Latino men in western attire dancing together and Guerrero’s photographic exploration of queer identity in Latino culture. Carrión calls it a very “poetic” work taken together.

“A lot of people are going to be able to walk through the galleries and see themselves in multiple spaces and also be able to learn about different iterations of cowboy culture,” she explained, later in our conversation adding, “Each artist and each community may have different answers to that question. We see different or individual takes on what cowboy culture means today, and the spectator is left to ask themselves, ‘what does cowboy culture mean to you?’”

—TARRA GAINES