A city floats a mile above the earth. Transparent modules glint with water vapor, neon pulses like a heartbeat, and the promise of a different kind of life hums in the air. This is The Hydrospatial City, the centerpiece of Gyula Kosice: Intergalactic, on view Oct. 26, 2025-Jan. 25, 2026 at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

“This is the first large-scale U.S. exhibition dedicated to Gyula Kosice,” said Mari Carmen Ramírez, Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the MFAH. “He was a visionary, one of the great theorists and avant-garde artists of his time. Yet his contributions remain quite neglected. Part of what this exhibition wants to do is reposition him in that conversation.”

The show arrives in Houston after traveling to the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA) and the Pérez Art Museum Miami. In some ways, it returns home: the MFAH acquired The Hydrospatial City in 2009, and the museum has a longstanding relationship with MALBA, having mounted six exhibitions together since 2005. Co-curated with Marita García of MALBA, Intergalactic brings together 75-80 works spanning four decades: kinetic sculptures, neon installations, and groundbreaking acrylic constructions that transform light, water, and air into artistic mediums.

1 ⁄8

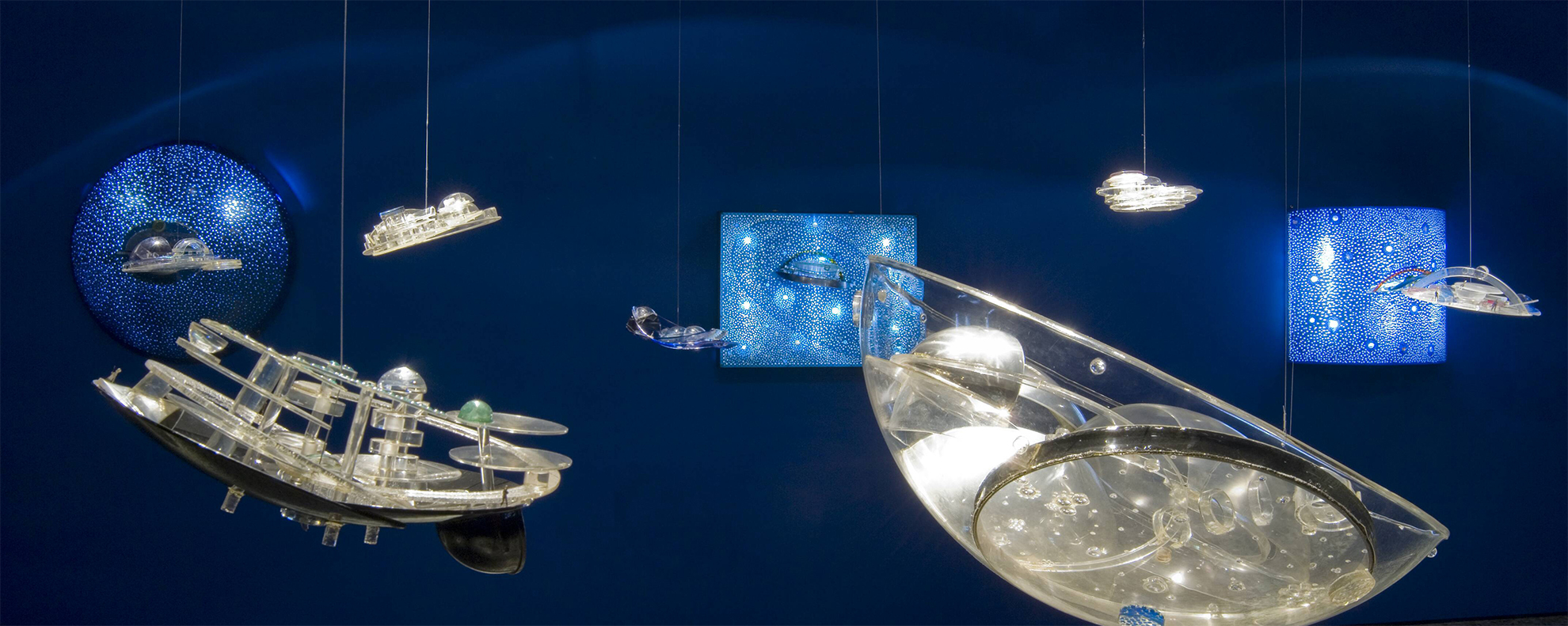

Gyula Kosice, Hábitat hidroespacial, maqueta B (Hydrospatial Habitat, Model B) [detail] from La Ciudad Hidroespacial (The Hydrospatial City), 1969, acrylic, paint, and metal, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires

2 ⁄8

Gyula Kosice in his studio, 1962, Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires. Image courtesy Malba –

Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

3 ⁄8

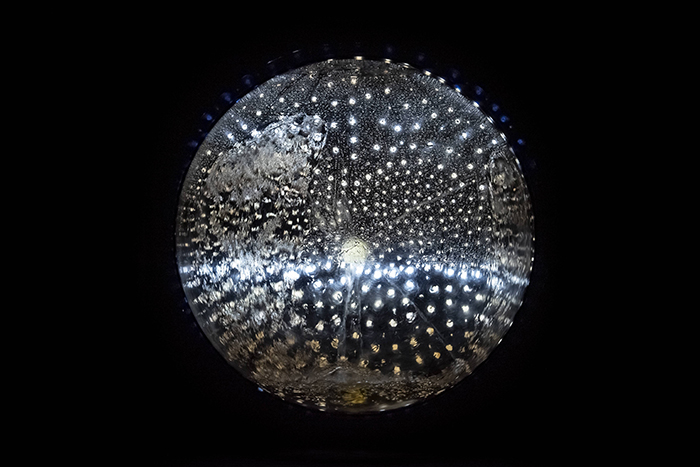

Gyula Kosice, Constelaciones no. 2 (Constellations no. 2) [detail] from La Ciudad Hidroespacial (The Hydrospatial City), 1971, acrylic, paint, and light, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires

4 ⁄8

Gyula Kosice, Tríada (Triade), 1960, acrylic, metal, wood, motor, and light source, Colección Museo Castagnino + macro, Rosario. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires. Image courtesy Malba – Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires; Santiago Orti, photographer

5 ⁄8

Gyula Kosice, Caja hidrolumínica (Hydroluminous Box), 1968, acrylic, wood, water pump, water, and light source, private collection. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires. Image courtesy Malba – Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires; Santiago Orti, photographer

6 ⁄8

Gyula Kosice, Goutte d'eau (Drop of Water), 1967–68, acrylic, private collection. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires. Image courtesy Malba – Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires; Santiago Orti, photographer

7 ⁄8

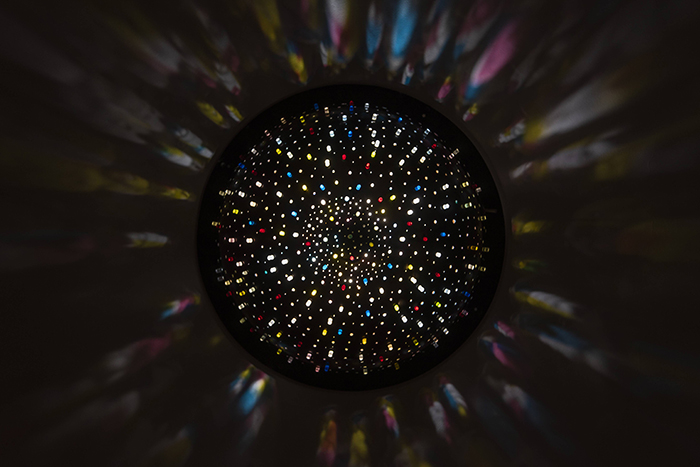

Gyula Kosice, Satélite de luz (Satellite of Light), 1970, acrylic, motor, and light source, Colección Navone. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires. Image courtesy Malba – Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires; Santiago Orti, photographer

8 ⁄8

Gyula Kosice, La ciudad hidroespacial (The Hydrospatial City) [detail], 1946–72, acrylic, paint, metal, and light, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment. © Fundación Kosice – Museo Kosice, Buenos Aires

“He worked with space as an autonomous entity,” Ramírez explained. “In this goal, he was aligned with other artists but always ahead of the times, looking forward toward the future.”

The exhibition emphasizes material research, both in Kosice’s practice and in its own installation. Plastics companies in mid-century Argentina encouraged artists to experiment, and Kosice approached the material systematically, forging a synergy between art and industry. At the MFAH, conservators and scientists have updated motors, neon tubes, and light systems to keep the works functioning, an act of preservation that mirrors Kosice’s own fascination with technological innovation.

If Kosice’s materials suggest futurism, his ideas were just as radical. The Hydrospatial City, conceived between 1946 and 1972, distills his utopian vision. Eleven light installations form constellations of habitats: a city in the sky powered by energy, capable of connecting with other modules anywhere around the globe. Kosice imagined these dwellings as a response to the environmental crisis and urban overpopulation, foreshadowing both the space race and contemporary debates about climate change and inequality.

Inside Kosice’s city, there is no kitchen, bedroom, or private home. Instead, spaces for reading, making love, writing poetry, and connecting with the creative aspects of humanity. It is a blueprint for a different social order. His habitats were never for profit; they were designed to enhance perception, to leave the viewer, or dweller, a better person. In this way, Kosice anticipated today’s immersive art while resisting its commercialization. His environments emerged from kinetic proposals, like the chromospectric tunnel, with the aim of transforming reality rather than selling an experience.

Organizing Intergalactic presented its own challenges. Kosice did not trust curators and often organized his own exhibitions. The artist’s archive, visited for the first time after his death, contained pieces that were not fully identified. Many works had fallen into obsolescence. Yet, as Ramírez recounts, the process also revealed his global reach: his presence in European and American collections, his correspondence with major artists, his restless drive to be ahead of his time.

“There exists a view that Latin American artists are capable practitioners but haven’t contributed to modernism,” Ramírez reflected. “I hope people realize Latin American artists are not just capable but have contributed major ideas, ideas that have impacted our understanding of art.”

—MICHAEL McFADDEN