When The Classics Theatre Project recently staged Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke in Fair Park’s Margo Jones Theatre, it was the first professional production of the play to be produced in the space since its world premiere there in 1947, when Jones herself was at the helm. More than 70 years later, Fort Worth-based freelance director Emily Scott Banks looked to the regional theater legend herself for guidance with the new production.

In addition to reading Jones’ biography and searching down every reference she could find to the script’s five extant versions, Banks pondered how the tiny, in-the-round theater could support what’s typically an extravagantly Southern production. The (not commercially successful) 1948 Broadway production followed Williams’ florid set design to the letter, but the dressed-down regional and later Off-Broadway productions actually connected much better with audiences.

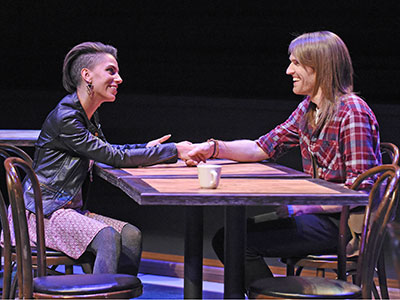

The Classics Theatre Project, a fairly new Dallas company, did not have the budget to invest in early-20th century costumes, nor did Banks care to pigeonhole the production as overly designed or old-fashioned. So modern dress it was, with café lights providing the romantic glow against which Alma, an unmarried minister’s daughter, problematically falls for John, the wild young doctor next door.

“Had we had the period filter, I think we could have managed to maintain the really dated (and rather fetishized) views of race and still not skewed the story away from Williams’ intent,” says Banks. “In my talks with POC artists in the community, the universal reaction was ‘yes, in modern dress to hear those lines from characters we are supposed to be empathetic with, it created challenges that were not the ones Williams intended.’ For the audience to buy into Alma’s journey, they have to understand her attraction to John. He needs to be problematic and crunchy, absolutely, but not a MAGA-hat-wearing racist. I believe part of keeping classics relevant now is treading this delicate balance: finding the way with each script and in the parameters of each production to create circumstances where modern audiences can receive the original intent and story.”

In her decade of professional directing, the former dancer (and award-winning actor) has led more than her share of challenging shows. She’s worked at nearly every professional theater in Dallas and Fort Worth, plus a few in Austin, and quickly became a sought-after interpreter of both classics and modern works.

Dan LeFranc’s non-linear The Big Meal was one such experience. Banks describes the play as “written musically, like a score and not a script,” and she approached the 2016 WaterTower Theatre production as the concerto it ended up becoming. As storylines crossed and generically named Shes and Hims met, fell in love, betrayed each other, and built new families that went out into the world to do it all over again, Banks spotted a connection to different periods in art that would both aid in the storytelling and signal to the audience where in the timeline they were landing.

Similarly, WaterTower’s 2017 production of The Gospel According to Thomas Jefferson, Charles Dickens, and Count Leo Tolstoy: Discord by Scott Carter immediately let its audience know that things were off-kilter by using a severely raked stage and trap door, out of which the historical figures popped to pontificate on both mankind and their purgatorial situation.

“I had this weird out-of-body thing where I envisioned super clearly that I wanted the whole idea to — contrary to what other productions do — enhance/represent the off-kilter/off-balance/no-expectations-met thing the characters are experiencing in … whatever we cosmically name this room they are in,” says Banks. “The script was super heady and super talky, and I know it may seem silly, but I was nervous a bit because it was my first time directing a cast of just men, and I knew I would have to have monster talents that could embody characters that were the rock stars of their age.”

Having a woman helm what is perhaps the most quintessential male coming-of-age tale — The Adventures of Tom Sawyer — may not have seemed an obvious choice, but Banks’ first directorial outing at WaterTower proved to be an education in child-like wonder.

“Pretty early on, I had this strong instinct that normal auditions would not do for what I wanted to accomplish,” she remembers. “We wound up having a two-hour group callback with movement, improv, and collaborative devising. Together, we would up with a truly opera-sized production: second-story rope swings, set floors with slides and traps, parkour, in-near-darkness choreography, crazy puppetry, and childlike magic — huge proof that if you cast the right folks, you can weather darned near anything with grace.”

But for every smooth production that Banks presents, she knows deep down that being true to the script and trusting her audience to believe in the magic of theater are the real keys to success. She recalls the 2017 Stage West production of Aaron Posner’s Stupid Fucking Bird, inspired by Chekhov’s The Seagull, as one prime example.

“My desire was to remove any and all barriers between the space, the actors, and the audience, to show all the ‘seams’ and all the grit of backstage, but then to still, oddly, let that transparency allow us all to go deeper into imagination together,” she says. “It was a magical show … hard — oh my god, so hard — but with a team like that, well … you just live for those, you know?”

-LINDSEY WILSON