On a November night in Paris in 1925, a collective of outlier artists launched a movement intent on tapping into unconscious creativity. A century later, surrealism’s unsettling imagery and thought-provoking themes still seem as timely as the years it was introduced.

Designed to pull the viewer in from the moment they gaze through a giant eye cutout set into an azure wall, the show is a collaboration with the Tate Modern and curated by that institution’s former senior curator, Matthew Gale. For Dallas, International Surrealism was adapted to bring dreamlike vibes into the exhibition’s staging, drawing viewers from the brightly lit opening room past a fun-house mirrored wall into a dark, womblike space that holds the show’s most compelling pieces.

“The Tate concept was built around these themes that are common to surrealism over many decades, expressed by artists in an original way: automatism, dreams, desires, and the influence of nature,” says the museum’s Pauline Gill Sullivan, curator of American art, Sue Canterbury.

1 ⁄8

Joan Miró, Women and Bird in the Moonlight, 1949, Tate, purchased 1951. © Successión Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2025. Photo: Tate.

2 ⁄8

Tristram Hillier, Variation on the Form of an Anchor, 1939, Tate, purchased 1984. © Estate of Tristram Paul Hillier. All rights reserved 2025/ Bridgeman Images. Photo: Tate.

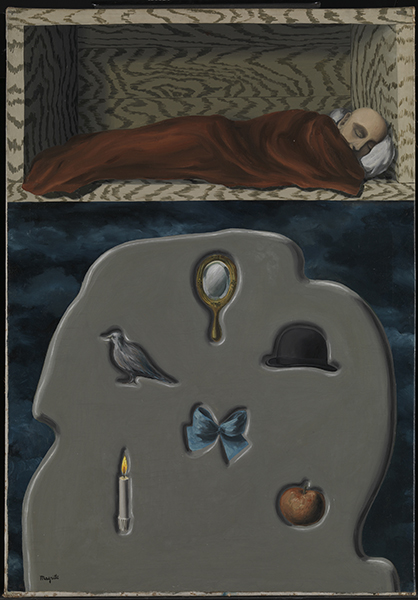

3 ⁄8

René Magritte, The Reckless Sleeper, 1928, Tate, purchased 1969. © C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Tate.

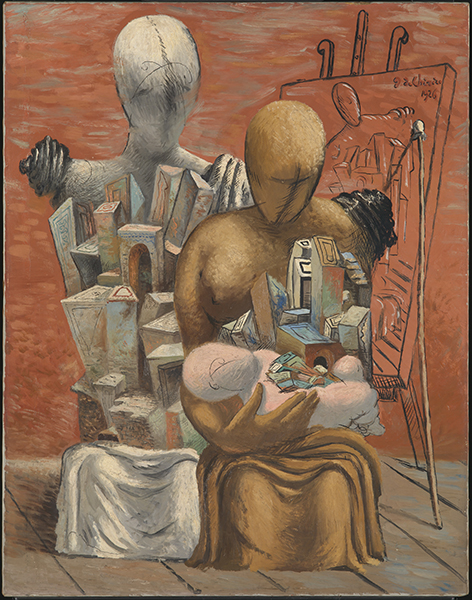

4 ⁄8

Giorgio de Chirico, The Painter's Family, 1926, Tate, purchased 1951. © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Tate.

5 ⁄8

Max Ernst, Men Shall Know Nothing of This, 1923, Tate, purchased 1960. © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Tate.

6 ⁄8

Enrico Baj, Fire! Fire!, 1963–64, Tate, presented by Avvocato Paride Accetti 1973. Courtesy Archivio Baj, Vergiate. Photo: Tate.

7 ⁄8

Wifredo Lam, Ibaye, 1950, Tate, purchased 1952. © Tate. Photo: Tate.

8 ⁄8

Salvador Dalí, Autumnal Cannibalism, 1936, Tate, purchased 1975. © 2025 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society. Photo: Tate.

Canterbury, who curated the Dallas presentation, notes “We broke up the exhibition in terms of this thematic breakdown and came up with a layout that would help create the sense of a dreamworld. So much of surrealism deals with the concept of perception and what we perceive with our eyes. Are we perceiving things accurately—what is fact? What is fiction? Is reality itself a construct? So much of surrealism is about provoking thought or reaction, so we wanted a space that would, in some sense, create that sort of discomfort when people walk into that first gallery.”

Greeted by the Italian painter Enrico Baj’s multimedia “Fire! Fire!” crafted from construction toys and oil on canvas, it is clear International Surrealism won’t hew to the usual suspects. Among the dreamscapes from bold-faced surrealist names (Breton, Dalí, Magritte), the Tate collection also features multiple works from Latin American artists and women who were essential to the surrealist movement, if a bit unsung during their lifetimes.

As the Dallas Museum of Art has been eyeing growth in its surrealist collection, Canterbury was particularly excited by pieces by Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, and Dorothea Tanning, whose “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” (a little night music) was a “holy grail get” she deems both quixotic and iconic.

Running throughout the show are dual threads of power and dissent. During the rise of fascism, Hitler deemed surrealism degenerate and morally corrupt, leading many of its artists to flee to the United States during World War II.

This includes an inspirational legacy leading to future movements like abstraction, spurred by the expat painters’ influence after they moved to New York. Pieces that seemingly don’t fit quite as neatly into surrealism’s parameters, including paintings by Jackson Pollock and Henri Michaux that “liberate the use of line” and photographs of seemingly banal tableaus by Eileen Agar and Dora Maar give International an eclectic edge Canterbury feels makes perfect sense.

“The surrealist crossed across everything—they did puppet shows, films, photography. There wasn’t a medium that was off limits to them, so it’s not a stretch to include those things. In terms of abstraction, the whole idea of automatism is something that Andre Breton emphasized through his readings of Freud… Breton thought it would be important for the surrealists to tap into this. Artists started to invent all these new techniques of scraping the canvas or pouring the paint.”

“Surrealism was a much more widespread movement than some people realize and had a much longer life,” she says. “It’s just really engaging work, and it deserves to be more well-known. I think the surrealists made a significant contribution toward freeing up artists and overturning all the restrictions they had from their academic training to start moving in new directions.”

—KENDALL MORGAN