From intricate sculptures carved from granite to precise brushstrokes on a canvas, art takes many forms. It could be drawings, pottery, jewelry or woodworkings. It could come from the mind of one of the Old Masters or your own child. A urinal can even become art.

Fountain would become one of Duchamp’s hallmark readymades, a term he created to describe the presentation of mass-produced everyday objects as art. Since Duchamp’s first readymades in the 1910s, his concept has endured within the art world. That includes the San Antonio Museum of Art’s (SAMA) exhibition Readymade Remix: New Approaches to Familiar Objects, running through April 12, 2026, where modern artists continue to innovate and create new readymade works.

“The exhibition starts with this idea of these mass-produced, readymade objects and materials that artists are drawn to, but looking at contemporary artists who are really kind of pushing those boundaries and really expanding upon that concept that Duchamp began over 100 years ago,” Lana Meador, SAMA’s Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, says. She adds that artists in this exhibit are “revealing other things about readymade that maybe Duchamp was ignoring,” such as the hidden labor that went into the pieces.

1 ⁄5

Matthew Angelo Harrison, American, born 1989, Beloved Worker, 2023, Hardhat, polyurethane resin, acrylic, and aluminum stand Overall: 55 1/2 × 13 1/2 × 10 1/2 in. (141 × 34.3 × 26.7 cm), Sculpture without base: 15 5/16 × 10 × 10 in. (38.9 × 25.4 × 25.4 cm), San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with The Brown Foundation Contemporary Art Acquisition Fund, 2024.3 © Matthew Angelo Harrison, Image courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco

2 ⁄5

Chuck Ramirez, American, 1962–2010, Gregory (Piñata Series), 2003, Ink jet print (aluminum backing), height: 60 in. (152.4 cm); width: 48 in. (121.9 cm); depth: 1 5/16 in. (3.4 cm), San Antonio Museum of Art, gift of Michael D. Maloney with conservation assistance from Patricia Ruiz-Healy, 2010.28.14 © Estate of Chuck Ramirez

3 ⁄5

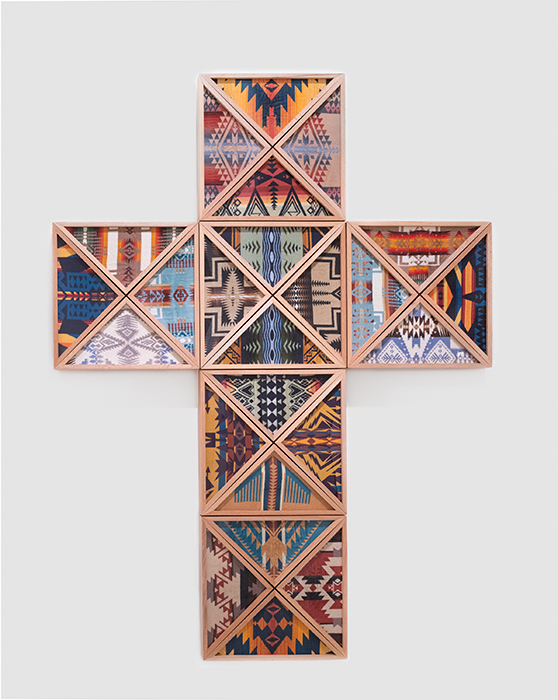

Joe Harjo, Muscogee Creek, born 1973, The Only Certain Way: Faith, 2019, 24 Pendleton beach towels, 24 custom memorial flag cases 78 × 104 × 4 in. (198.1 × 264.2 × 10.2 cm), San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with The Brown Foundation Contemporary Art Acquisition Fund and funds provided by Dr. Katherine Moore McAllen, Dr. Dacia Napier, Edward E. (Sonny) Collins III, and The Sheerin Family, 2021.3.a-f © Joe Harjo

4 ⁄5

Patrick Martinez, American, born 1980, Jaguar Guardian, 2024, Stucco, neon, mean streak, ceramic, acrylic paint, spray paint, latex house paint, banner tarp, rope, stucco patch, ceramic tile, tile adhesive on panel, 60 × 120 × 5 in. (152.4 × 304.8 × 12.7 cm), San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with The Brown Foundation Contemporary Art Acquisition Fund, 2024.12, © Patrick Martinez, Image courtesy of Charlie James Gallery

5 ⁄5

E.V. Day, American, born 1967, Winged Victory, 2002. Red sequin dress, organza gloves, synthetic eyelashes, acrylic nails, monofilament, hardware, and mirror-polished steel base. Variable dimensions: 115 × 92 × 100 in. (292.1 × 233.7 × 254 cm); San Antonio Museum of Art, gift of Jereann and Holland Chaney, 2024.5, © E.V. Day

The new acquisitions include E.V. Day’s piece, Winged Victory, from her captivating Exploding Couture Series. The work takes inspiration from the Greek Goddess of Victory, Nike, and features shreds of a red sequined dress suspended in the air. “It’s incredibly impressive. It’s a real feat of engineering,” Meador says, noting it was an “all hands on deck” installation with the piece utilizing 180 eye hooks and 237 monofilament strands.

Another new addition is Jaguar Guardian by Patrick Martinez. “It appears like it’s the facade of a local storefront that’s been taken off the streets of an LA neighborhood and placed right into the gallery,” Meador says, adding that the exterior even includes neon lights. “He has painstakingly created that surface, layer upon layer of stucco…power washing it to really mimic the way that these surfaces are weathered and treated, and the histories that they have when they are in an urban landscape.”

Rounding out the trio of newly acquired works is Matthew Angelo Harrison’s Beloved Worker, an Exxon employee hard hat encapsulated in the resin form of a face mask from the Dan people of Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia. It’s thought the masks have spiritual power, tying together the protective forms of the mask and hard hat. Meador sees Beloved Worker as speaking to the labor involved in readymades as well as creating a dialogue between the digital and the analog in its creation. Additional works in the exhibition include pieces from San Antonio artists Joe Harjo and Chuck Ramirez. Harjo’s The Only Certain Way: Faith features a giant cross constructed out of memorial flag cases containing folded, mass-produced beach towels adorned with Native American designs. “It’s really impactful,” Meador says.

“He’s taken these Santos figurines from a botanica, and instead of photographing them as you would to see the whole figurine, he’s turned them upside down, and he’s photographing the undersides so they become these really interesting abstractions,” Meador explains, comparing them as akin to archeological objects and describing how the artist named and ordered the photos based on the nine-part grid of The Brady Bunch intro. The Santos series will then rotate with Ramirez’s Gregory depicting a pummeled Hello Kitty piñata against a bare white background in the context of a glossy advertising print.

Meador sees the various unique pieces and reframings of the readymade concept in this new exhibition as an opportunity to “stop and reconsider the legacy of Duchamp and how maybe these artists are pushing that forward in a different way.” Likewise, she sees Readymade Remix as a chance for younger audiences and artistic newcomers to see the multi-layered meanings embedded within readymade works such as these.

“I hope people are inspired by the multitude of ways that different materials can be transformed, and perhaps that they can do that themselves in some way,” Meador says. She hopes it “makes them think a little bit more about the objects that they see on a daily basis” and how those materials are “important and meaningful.”

—BRETT GREGA