It’s 1992 at Glasgow School of Art. A seven-foot-by-six-foot painting that portrays a thick, fleshy female nude, subtly snarling and sitting on a pedestal, towers above visitors to an undergraduate exhibition. The piece, titled Propped (1992), was just one in the debut of British artist Jenny Saville’s first “mature pictures.” The show launched Saville into the international spotlight at age 22, helping to secure her spot among the YBAs (Young British Artists) of the ʼ90s.

This fall, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth opens Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, on view Oct. 12, 2025 through Jan. 18, 2026.

“Jenny Saville is one of the most important figurative painters working today, and her influence is visible in the work of nearly every figure painter who has followed her,” says Andrea Karnes, The Modern’s chief curator. “Her paintings carry a powerful emotional resonance, provoking awe, discomfort, and empathy in equal measures. Over time, she has shifted from realism to works that reflect the complexities of our digital and virtual world, while always keeping the body at the center of her practice.”

That shift is reflected in The Anatomy of Painting, which features fifty oil paintings and charcoal drawings, combined, that trace the arc of Saville’s career, including Propped. Organized by the National Portrait Gallery, London, and Senior Curator of Contemporary Collections, Sarah Howgate, and overseen by Karnes, the exhibition is the first one to be presented at a major U.S. museum.

1 ⁄10

2 ⁄10

3 ⁄10

4 ⁄10

5 ⁄10

6 ⁄10

7 ⁄10

8 ⁄10

9 ⁄10

10 ⁄10

Karnes explains, “Sarah and Jenny Saville worked together on the core checklist. Then, Jenny and I worked closely together to shape the Fort Worth presentation, adding eleven major works from U.S. collections that could not be shown in London for various reasons, like scale, fragility, or shipping challenges. This version feels special to The Modern because it’s bringing together works that the artist is excited to see in conversation with one another for the first time in a long time, or maybe ever.”

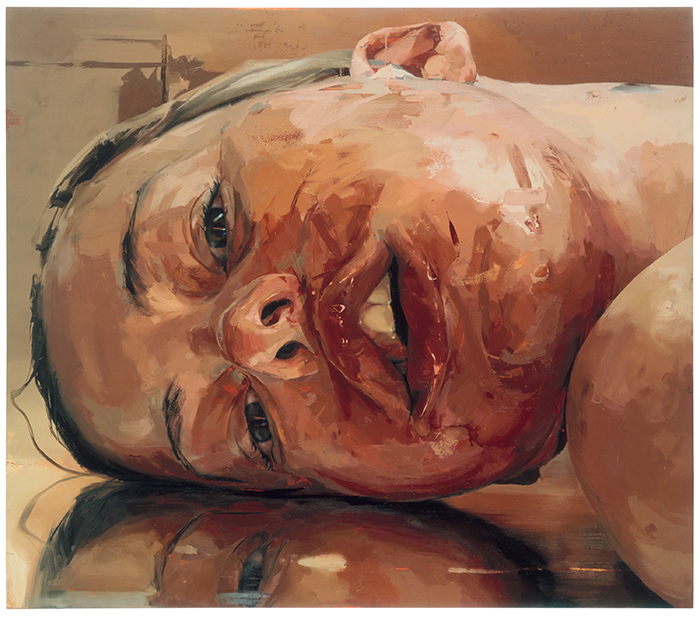

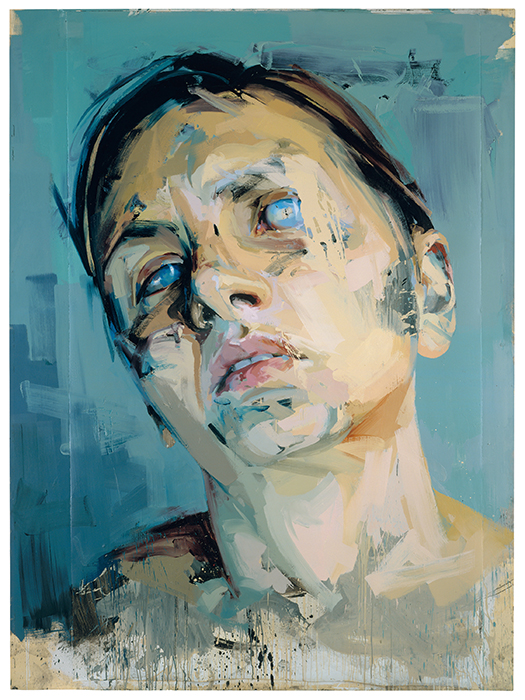

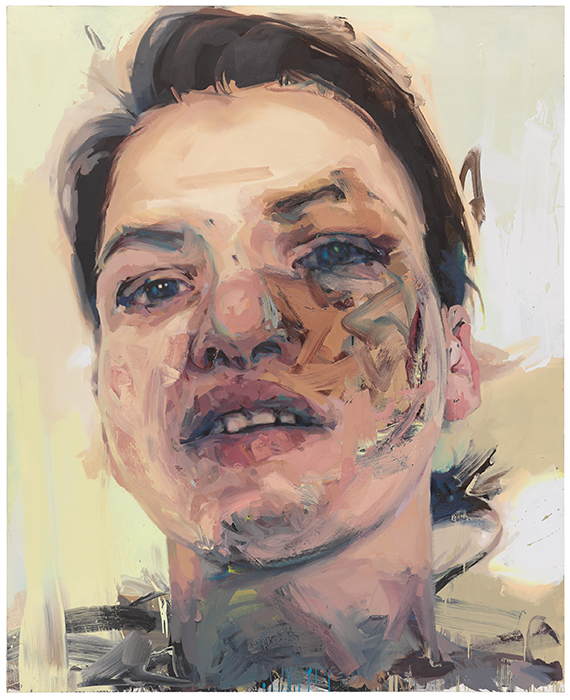

Rather than seamlessly rendered, Saville’s painted faces and figures are physically built up with oil pigment, layered similarly to how the muscles, fat, veins, blood, and skin comprise the body. Saturated blues, reds, and yellows live amidst familiar olives, pinks, and browns that keep human flesh and its complexities ever-present.

And with life comes death.

“Death runs as an undercurrent through Saville’s work, and it is often entwined with life, resilience, and transformation. Early paintings drew on medical imagery, while later works such as those with her Pietà references echo grief as well as survival,” says Karnes. “Rather than isolating death, Saville places it inside a larger meditation on the human condition.”

The painting Rosetta II (2005–06) portrays an opaque-eyed young adult, head tilted back and off to one side, with an institutional blue-green-grey backdrop. It may be amusing to think of this posture as one we embody after a long day in front of the computer, blinded by blue light. But the portrayal is all the more poignant—even horrifying—when we consider contemporary cultural habits that deaden our senses. We look at images all day long but no longer recognize what’s real. Reverse (2002-2003), with its head-on-the-floor perspective, makes eye contact a strained and unrewarded effort. Mouth agape, slouched, and wet, the subject’s head lies on a reflective surface with visible dead weight, as though after a collapse.

Karnes says, “The Modern has a long tradition of collecting artists who centered their practices on the figure—Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, and Willem de Kooning, among them. Many of these artists were influential to Saville. These connections situate her in dialogue with great painters who came before her, but what makes her remarkable is that she claims the figure entirely on her own terms. She is both inheritor and radical reinventor.”

Saville’s works do indeed propose reinvention as the key to renewal. Back in 1992 at Glasgow, Saville displayed Propped opposite a mirror so that the words by French feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray, which the artist had scratched into the paint, were legible: “If we continue to speak in this sameness—speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail each other.”

—NANCY ZASTUDIL