Nam June Paik’s faint inscription, It rains in my TV as it rains in my heart, drifts between a drawing, a poem, and a weather report. The phrase, written in delicate strokes, blends into the static of Lines of Resolution: Drawing at the Advent of Television and Video at the Menil Drawing Institute, a show that traces how artists between the 1950s and 1980s used the television not only as an image source but as a drawing instrument, a collaborator, and sometimes an adversary.

“In 1950, about nine percent of households in the U.S. owned a television,” Lovatt noted, “and by 1960, that number was around ninety percent.” It was a moment when artists and audiences alike were learning to live with the screen’s flickering presence. The small, glowing box entered the studio as both muse and mirror, an object whose hum could not be ignored.

Lovatt began the research that would become Lines of Resolution during her 2022 fellowship at the Menil Drawing Institute. She was drawn to the ways artists used drawing to translate, resist, and reimagine televised images. While studying the Menil’s holdings of Walter De Maria drawings, sketches of television sets rendered as radiant boxes, she began to see how artists were reflecting on the object itself, its aura, its rays.

“The television wasn’t just furniture,” she said. “It was this physical, almost sculptural presence in the room.” From there, the project grew into a broader investigation of the relationship between drawing, television, and early video.

1 ⁄7

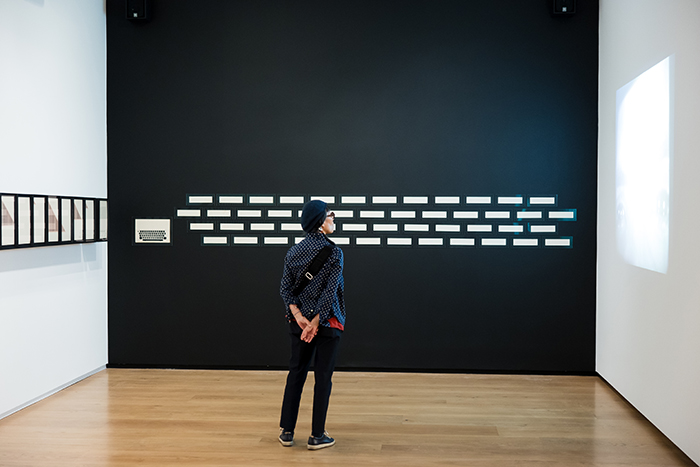

Installation image, Lines of Resolution: Drawing at the Advent of Television and Video at The Menil Drawing Institute.

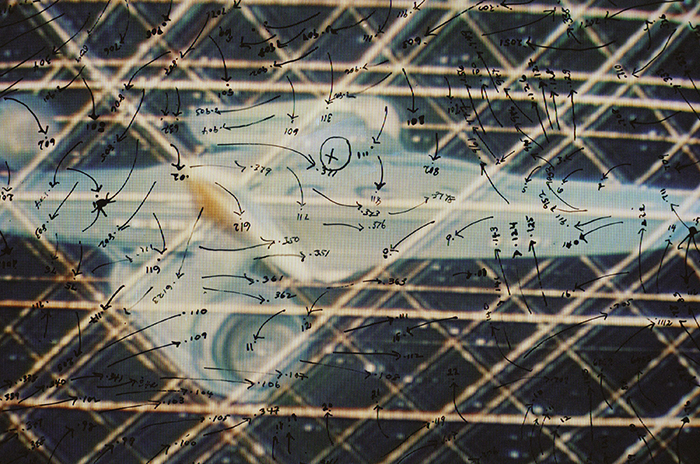

2 ⁄7

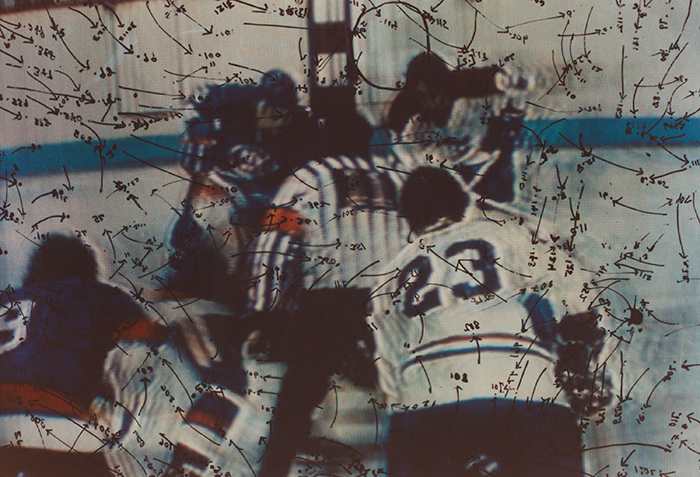

Howardena Pindell, Video Drawings: Hockey, 1975. Chromogenic print, 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, NY. © Howardena Pindell. Image courtesy of Greenan Gallery, NY

3 ⁄7

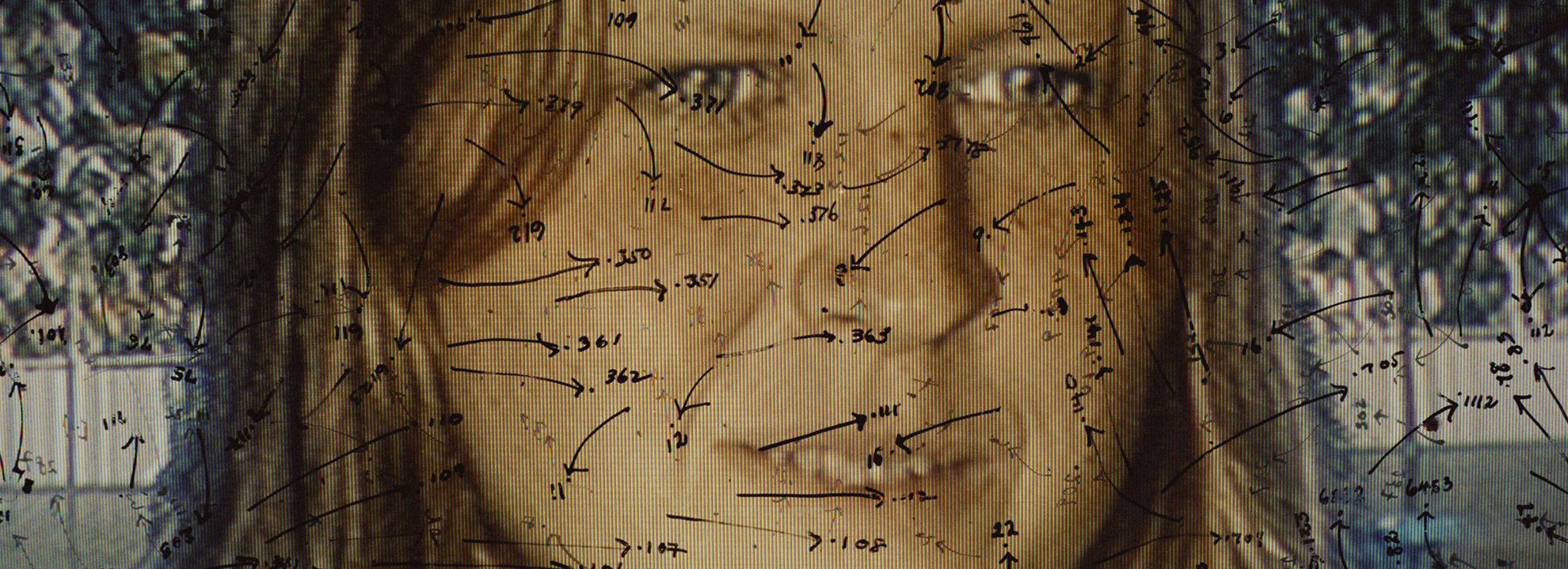

Howardena Pindell, Video Drawings: Science Fiction (Star Trek), 1975. Chromogenic print, 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, NY. © Howardena Pindell. Image courtesy of Greenan Gallery, NY

4 ⁄7

Sanja Iveković, Instructions No. 1 [Instrukcije br. 1], 1976. Single channel video, black-and-white with sound, Duration: 6 minutes. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © Sanja Iveković, Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

5 ⁄7

Howardena Pindell, Tokyo TV #6: (Sumo Wrestler), 1975. Chromogenic print, 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, NY. © Howardena Pindell. Image courtesy of Greenan Gallery, NY

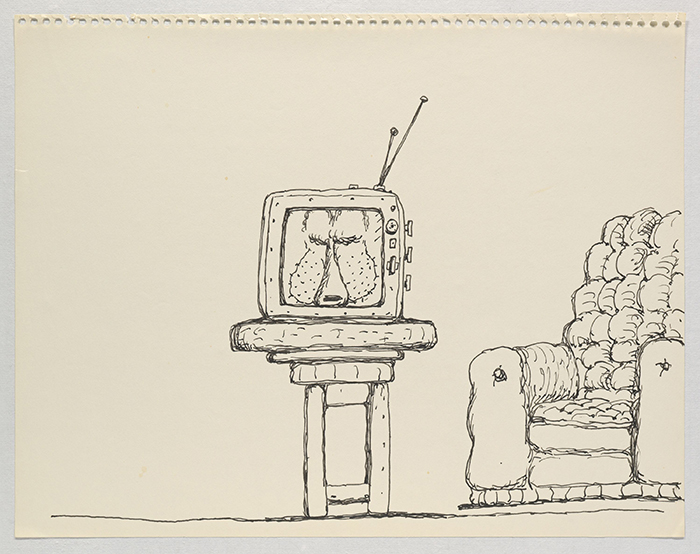

6/7

Philip Guston, Untitled, 1971. Ink on paper, 10 3/4 × 13 7/8 in. (27.3 × 35.2 cm). Private collection, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

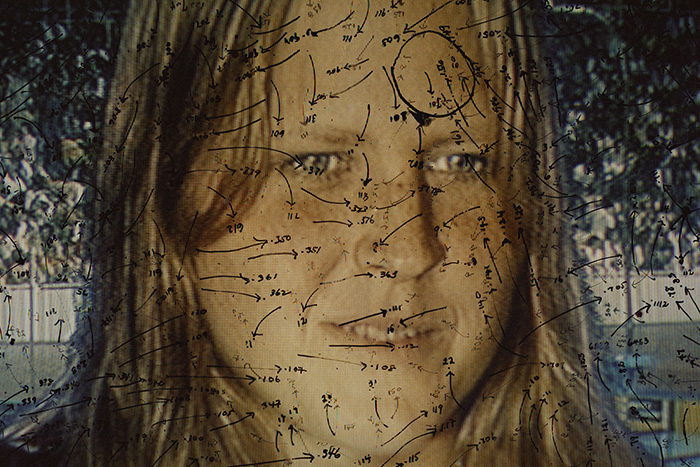

7 ⁄7

Howardena Pindell, Video Drawings: News, 1975. Chromogenic print, sheet: 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm), frame: 16 1/8 × 13 3/8 × 1 1/2 in. (41 × 34 × 3.8 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, NY. © Howardena Pindell. Image courtesy of Greenan Gallery, NY

At the heart of the exhibition is the idea that television’s formal language, the scanline, the flicker, the feedback loop, could be absorbed into the gestures of drawing. For some artists, this meant rethinking the mark itself.

Paik’s Zen for TV (1963/64), reduced to a single glowing line, transforms the medium’s noise into quiet. For others, the technology became a surface for intervention. Howardena Pindell used static electricity to attach clear acetate sheets to her television screen, drawing dots, numbers, and arrows atop the broadcast image. She called these “video drawings,” an apt phrase for the exhibition’s central proposition: that television and drawing might share the same pulse.

In Dennis Oppenheim’s A Feedback Situation (1971), a father draws on his son’s back as the boy attempts to reproduce the gesture on his father’s skin. The act, recorded on video, is both intimate and instructional, a study in transmission and translation. Lovatt sees in Oppenheim’s work a model for how artists of this era began to “perform drawing for the camera,” shifting the medium from static object to time-based event. The result is a kind of choreography between hand and image, one that anticipates today’s touchscreen gestures and their constant feedback.

As television became more accessible and video cameras entered the domestic sphere, artists, especially women, found in these technologies a means of self-examination and critique.

“From around 1970, we noticed an abundance of women working with the video camera and performing drawing for the camera,” Montana explained. “Independent of each other, across Germany, the UK, Canada, Brazil, and Yugoslavia, they were all using video to respond to media representations of women as they were being broadcast.”

While Lines of Resolution includes canonical figures like Paik, Sigmar Polke, and Robert Rauschenberg, it gives equal weight to artists whose names are less familiar but whose contributions reframe the narrative of media art. Ursula Wevers and Dov Eylath treat the signal as line, bending interference into abstraction; Teresa Burga and Nina Sobell use early video to test how identity and authorship can be drawn, erased, and re-drawn in real time. Together, these artists expand drawing beyond graphite and paper, recasting it as an action that can occur anywhere an image flickers.

The exhibition’s installation balances the glow of the TV with the quiet of paper. Montana describes the design as pragmatic rather than theatrical: “We did think it was important to have one gallery with a black-box style to foreground that mode of viewing, but otherwise we wanted each work, video or drawing, to be seen in its best light.”

This care is palpable. Moving through the galleries, viewers drift between the tactile and the ephemeral, between the hand’s pressure and the signal’s pulse. The rhythm of looking becomes part of the exhibition’s structure, echoing the alternation between concentration and distraction that television first made habitual.

By concluding in the mid-1980s, the show captures a pivotal hinge between the analog and the digital, when artists still worked within a shared televisual field. After this moment, as Lovatt notes, “the emergence of cable television and video recorders meant that television became less of a collective experience and more individualized.”

Yet the questions posed by these works remain startlingly current. The gestures of self-recording, the feedback between subject and screen, the blur between seeing and being seen, have all migrated into contemporary life.

The exhibition suggests that these early artists were not simply responding to technology but writing its first grammar. Their lines, whether on paper, acetate, or cathode ray, trace the beginning of a new way of seeing, one that continues to shape how we relate to our screens and to ourselves. In that sense, Paik’s melancholic line feels prophetic. It speaks to the porous boundary between the external world and the emotional one, between weather and signal, between the rain outside and the static within.

Lines of Resolution asks viewers to slow down, to notice how a single mark might carry the weight of an image, how a flicker might stand in for a thought. It reminds us that the screen was never purely mechanical; it has always been, in some sense, a mirror. When Paik wrote that it rains in his TV as it rains in his heart, he wasn’t describing two separate storms. He was tracing the line that connects them.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN