A documentary photograph can make a promise and then break it. It can show a face and still refuse familiarity. It can record a public event and still leave the viewer alone with private doubt. Photography from The Menil Collection: Curated by Wendy Watriss leans into that tension. On view at the Menil Collection through May 31, 2026, the exhibition brings together twentieth-century documentary work by Larry Burrows, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Danny Lyon, Charles Moore, and others, and asks what happens when “evidence” does not behave like an answer.

At the Menil, Watriss treats the collection as a living record of taste and conviction, not as a clean survey of movements. In the press release announcing the show, she describes the exhibition in terms that set the tone for how it unfolds in the galleries: “This is an unconventional exhibition. It was done by three sets of eyes: my own and what I know about the vision of the two remarkable people who collected these photographs, John and Dominique de Menil.” She continues, “Being invited by the Menil to curate a show from the museum’s photography collection has been a very special gift. It has given me the opportunity to reconnect with their vision and their remarkable way of interacting with art and the world.”

That “unconventional” quality is not a branding gesture. It describes an approach to sequencing that resists the standard documentary arc of suffering-to-revelation. Watriss’s early galleries emphasize portraits and near-portraits, figures who meet the camera with self-possession rather than appeal.

1 ⁄6

Bruce Davidson, East 100th Street, 1966. Gelatin silver print. 7 3/16 × 7 3/16 in. (18.3 × 18.3 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston, Anonymous gift. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos. Photo: Paul Hester.

2 ⁄6

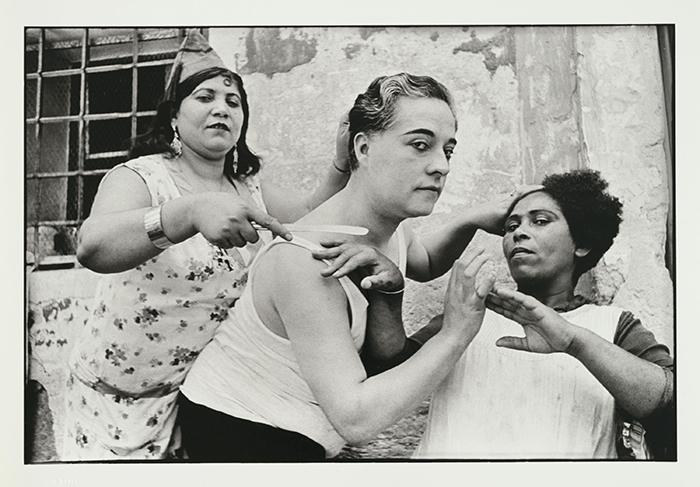

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alicante, Spain, 1933, printed 1985. Gelatin silver print, 9 3/8 × 14 1/4 in. (23.8 × 36.2 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos.

3 ⁄6

Marc Riboud, Untitled, 1967. Gelatin silver print, 5 3/4 × 8 1/2 in. (14.6 × 21.6 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Marc Riboud / Fonds Marc Riboud au musée Guimet / Magnum Photos. Photo: James Craven Walker.

4 ⁄6

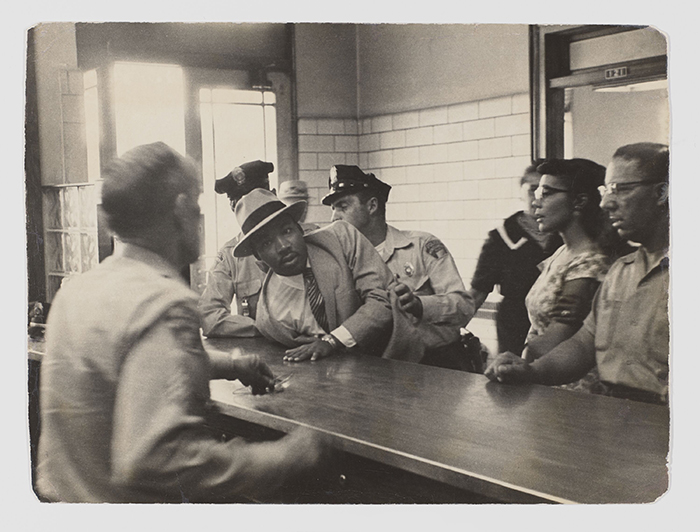

Charles Moore, Martin Luther King Jr. is Arrested for Loitering Outside a Courtroom Where his Friend Ralph Abernathy is Appearing for a Trial, Montgomery, Alabama, 1958. Gelatin silver print, 10 1/4 × 13 1/4 in. (26 × 33.7 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of Adelaide de Menil and Edmund Carpenter. Photo: James Craven.

5 ⁄6

Pierre Verger, Untitled (Portrait of a Wayri Ch’unchu, Fiesta de Corpus Christi, Ocongate, Cuzco, Peru), 1939–45. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 7 1/4 in. (20.3 × 18.4 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Fundação Pierre Verger. Photo: Jennifer McGlinchey

Sexton"

6 ⁄6

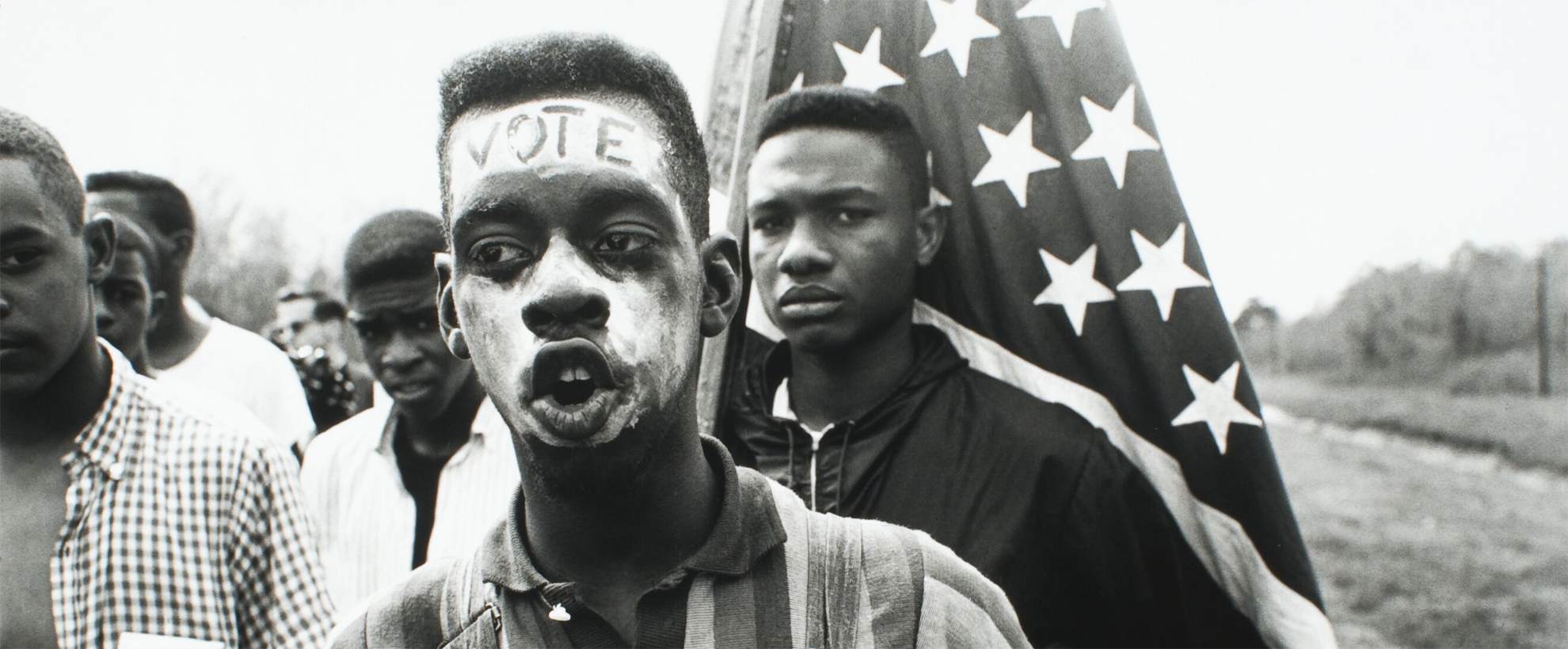

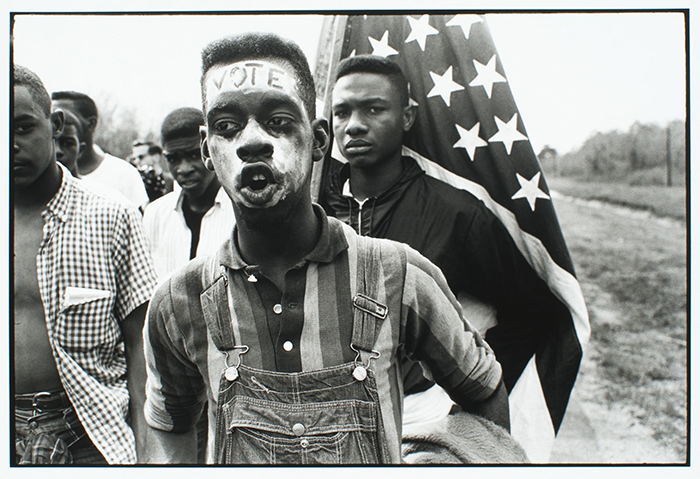

Bruce Davidson, "VOTE" Marcher, Selma, Alabama, 1965. Gelatin silver print, 11 × 14 in. (27.9 × 35.6 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of Edmund Carpenter and Adelaide de Menil. © BruceDavidson/Magnum Photos. Photo: Paul Hester.

“If one looks at the show carefully, the first third of it are portraits,” she said. “They’re portraits not of people suffering or starving, but of people who have a strong sense of self.” The photographs do not flatten their subjects into types. They hold a line against the viewer’s desire to feel informed too quickly.

Watriss frames this resistance as an ethical problem, but also as an aesthetic one. “One of the ways that I felt the three of us coincided, myself and the two of them, was that we didn’t want stereotypes,” she said. “We were independent thinkers, and I chose pictures that didn’t conform to what was expected.”

In her account, the de Menils’ commitments to civil rights and human equity were not separate from their visual appetite; the collection, at its best, shows a preference for images that complicate the viewer’s first read. A key example is the Walker Evans photograph she places at the beginning of the show, a dockworker in Havana. Watriss describes the picture as a meeting, not a capture.

“This dockworker has this quizzical, ironic sense of ‘I know who I am,’” she said. “It’s like he’s willing to engage with you, but you don’t know him, really.” For her, the power of the image lives in that distance. “It has an ambiguity about it, and it challenges the viewer to think about what it is they are seeing.”

As the exhibition advances, the portraits give way to collective struggle: nineteenth-century photographs that surface the long architecture of race in the United States, then civil rights imagery that grows harsher as it accumulates, followed by apartheid, protest, and war. Watriss builds these transitions through visual hinges rather than clean chapters. She describes “mask” images as one of the show’s turning points, because they force the viewer back onto the act of looking at itself. “Their intention is to ask you again, ‘What is it that you’re actually seeing?’” she said. “Who are you, and what is this that you’re looking at?”

The shift into Vietnam, through Larry Burrows’s photographs, marks a different kind of viewing. If the early galleries ask the viewer to sit inside ambiguity, Burrows pushes the viewer into a clarity that hurts. “With Larry Burrows’s work in Vietnam, there’s no doubt about what you’re seeing,” Watriss said. “He wants you to see every painful aspect, every bandage, every movement that is hard, every moment of waiting for a helicopter to pick the wounded up.”

Watriss’s exhibition feels less like a summary of documentary photography than a lesson in how documentary images keep working after the headlines move on. The photographs ignite conversation, as the Menil puts it, but they also resist consumption. They keep their subjects whole by denying the viewer easy access. They ask for time. They ask for doubt. They ask for a kind of looking that does not end with recognition.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN