In Timothy Harding’s paintings, there’s a kind of friction at play, a low hum between precision and improvisation, between gesture and grid, between what is seen and what is suggested.

Harding’s upcoming exhibition, Strange Expanses, at the Old Jail Art Center in Albany, Texas—a solo entry in the museum’s Cell Series, on view from Sept. 27, 2025, to Jan. 10, 2026—continues that inquiry.

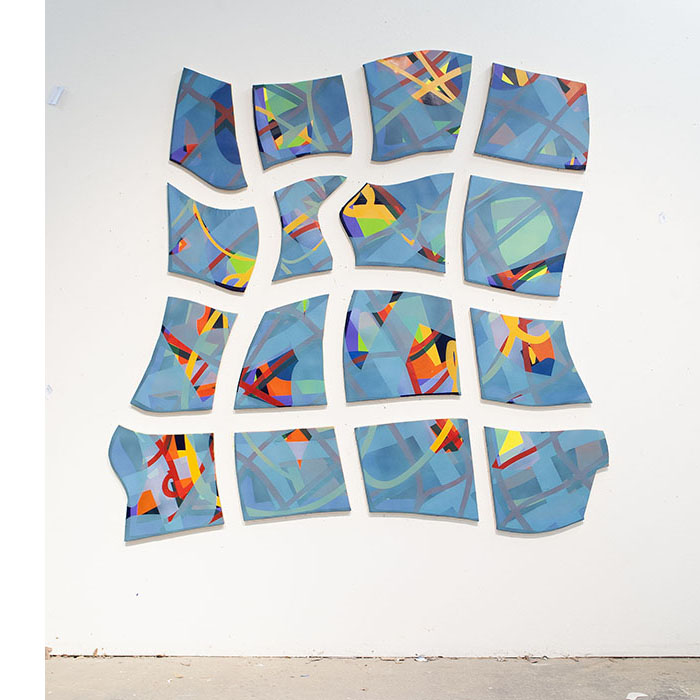

It marks an evolution in his thinking about space, surface, and the slippery limits of painting as both object and illusion. These new works, built from multiple panels, carve into the wall itself. Gestural voids slice through their geometry like handwriting erased mid-mark, implicating architecture as part of the form. The painting is not just a painting; it is a negative impression: a presence, and an absence.

1 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Polyptch in 16 Parts, acrylic on canvas over panel, 84” x 89”, 2024, photo courtesy the artist.

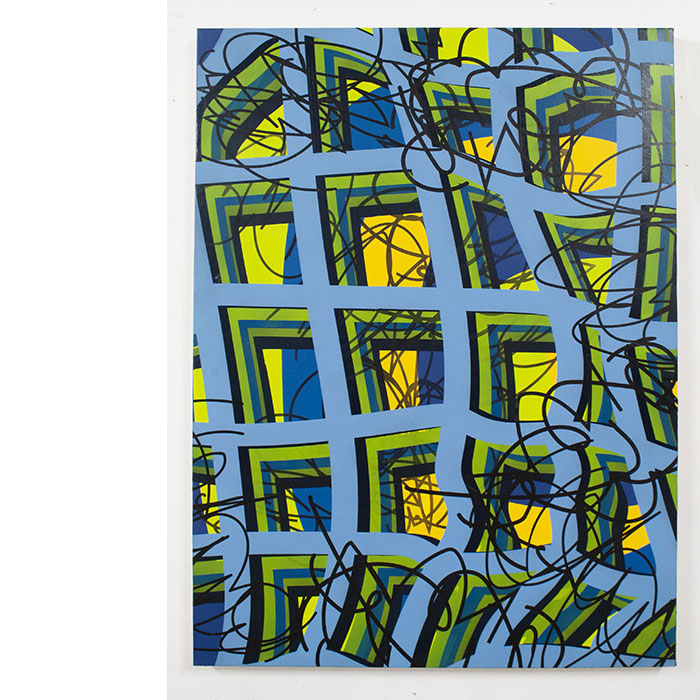

2 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Blue Grid with Concentric Circles, acrylic on canvas, 72” x 50”, 2024, photo courtesy the artist.

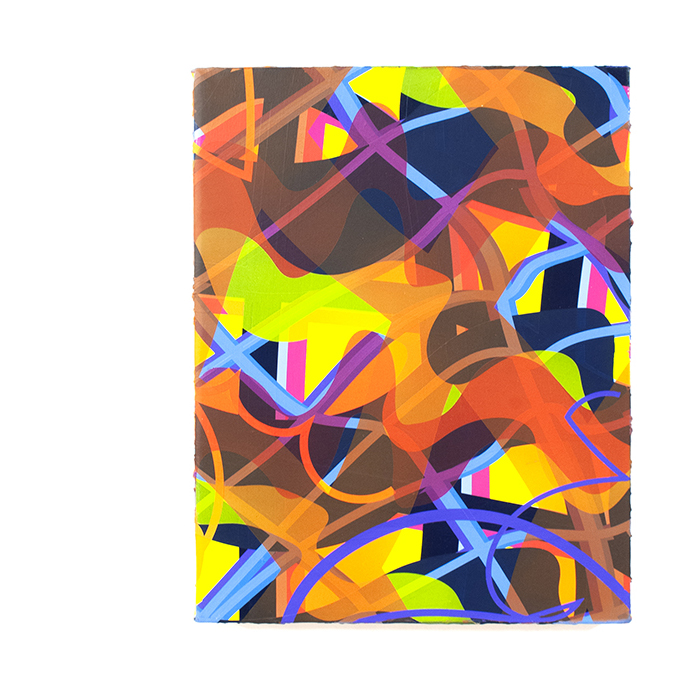

3 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Warm Glazes over Forms, acrylic on canvas, 21” x 16”, 2024, photo courtesy the artist.

4 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Yellow Glaze with Blue Gestures, acrylic on canvas, 21” x 16”, 2024, photo courtesy the artist.

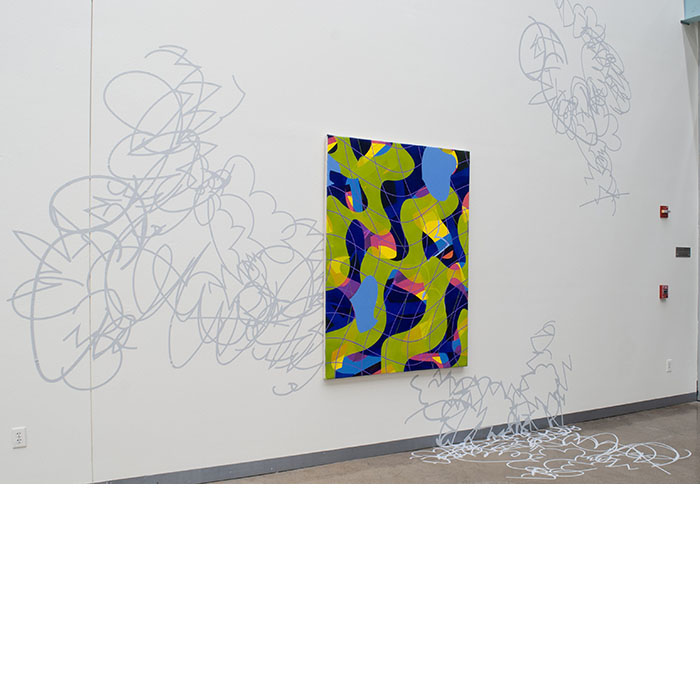

5 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Grid with Ghost Forms (installation view), acrylic on canvas with site-responsive adhesive vinyl, 72” x 50”, 2024, photo courtesy the artist.

6 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Adjustment IV, acrylic on canvas, 48” x 36”, 2021, photo courtesy Kevin Todora.

7 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, 8. 40" x 32" on 34" x 26" (Pink and Orange under Gray), acrylic on canvas, 36” x 28” x 4”, 2017, photo courtesy the artist.

8 ⁄9

Timothy Harding in his studio. Photo by Kalee Appleton.

9 ⁄9

Timothy Harding, Polyptch in 31 Parts, acrylic on canvas over panel, 96” x 96”, 2025, photo courtesy the artist.

That statement, modest in delivery, feels central to his practice. Harding is less interested in defining what painting is than in asking where it begins and where it ends.

In the last decade, he’s built installations from cut paper, constructed linear forms from CNC-cut wood, layered vinyl gestures across gallery walls, and pulled painted canvas through sculptural grids. He works in both literal and conceptual layers, building a visual archive over time.

Still, the paintings remain at the core. Their aesthetic draws from abstraction, but not with the heroic mythology of mid-century gesture. Instead, Harding’s forms often begin in Adobe Illustrator, a digital sketchbook of parts he revisits and recombines: grids, loops, marks, structures.

Fragments from past works are stored, recalled, manipulated, and reconfigured. Once a composition starts to take shape, he sends the vectors to laser cutters, vinyl plotters, or CNC machines, generating stencils and forms to mask and layer paint, often in a process closer to screen-printing than traditional brushwork.

There’s an obvious risk to working this way: the art could feel cold, too clean. But Harding circumvents that by embracing disruption.

“I want to maintain some kind of conversation with the physicality of installation,” he said. In early works, he distorted the finished paintings by stretching them onto smaller subframes, forcing the canvas to warp and fold. Recent series, like Adjustments, reverse that impulse, flattening the surface while revealing the wooden grid beneath, like a skeleton pressing up from under the skin.

“I am interested in the challenge of making something on the computer and then trying to recreate that in physical form,” he said. “Using tools to aid along the way, I find it motivating to achieve a level of craft in the completed work that might cause a viewer to wonder how it was made. Many times, the digital imagery, whether it’s a wavy grid or gestural mark, has roots in something that at one point was a physical thing from the world made by my hand.”

The grid, too, plays a recurring role, not as strict logic but as a point of familiarity. “It’s universally recognizable,” he explained. “A way to engage the viewer without being overtly specific.” In some works, the grid wavers, warps, or disappears. In others, it provides the base structure from which everything else deviates.

In recent multi-panel paintings, the grid arrives not as rigid order but as fracture. The surface appears cut, spliced, and rearranged: a field of saturated shapes bending under their own geometry. There’s no single point of entry. Instead, you move through it, your eye caught in waves of green and violet, then jolted by the insistence of yellow and orange. The cut lines function both as compositional device and architectural strategy, fractures that pull the viewer in, then out, and back again.

Harding often spoke of “play” in the studio, but it’s not improvisation for its own sake. It’s a form of critical curiosity. How far can the painting go before it’s something else? How can precision contain ambiguity? How does space behave when it’s both rendered and real?

There’s a generosity in that gesture, an openness mirrored in Harding’s reflections on process. His influences are varied: Joan Mitchell’s color, Judd’s rigor, Irwin’s space, Stella’s refusal to stay still. But Harding’s voice is his own. He moves between minimalism and illusion, between sculptural form and chromatic depth, not to fuse them into a single language, but to keep the conversation open.

“I simply hope people find themselves looking at the world around them differently,” he said. “It can be something as simple as how light falls across a form to produce a shadow just so.”

In Harding’s work, that shadow might just be the painting itself.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN