“dada is for nature and against ‘art.’”

—Jean (Hans) Arp

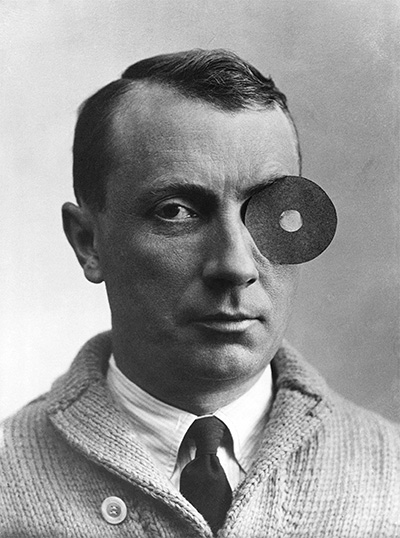

Photo courtesy Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth.

At Dallas’s Nasher Sculpture Center through Jan. 6, The Nature of Arp considers Jean (Hans) Arp’s diverse production through his processes, linking them to the processes of the natural world. That is, while we could easily think about Arp’s biomorphic forms as visual parallels for natural things we recognize—this sculpture looks like a leaf or a stone or a hill or an animal, we might say—the show insists instead on seeing Arp’s creative process in relation to the verbs of the natural world: “the way a stone breaks off from a mountain, a flower blossoms, or an animal perpetuates itself.”

One of the founding members of Zürich Dada, Arp was an artist whose sculptures, works on paper, collages, and poetry grew from each other, metamorphosed, and wrapped around each other in a mélange that remains difficult to divide out into its various parts.

Add to that his interest in collaborative practices and it becomes very difficult to make a retrospective exhibition that trumpets his individual genius. Here, instead, the Nasher does what it does best: The Nature of Arp is a thoroughly researched yet approachable exhibition installed to perfection with an innovative take on an historic artist who we thought we knew. It’s a creative and generous curatorial approach that makes Arp’s body of work visually fresh and conceptually relevant again.

While any intro art history text will explain that Dada was about exploring absurdity and the unconscious, The Nature of Arp connects Dada artists’ playful unpredictability into other and ongoing conversations. Among other things, the exhibition considers how Arp saw the movement as a challenge to broader social constructs of artist-as-genius: “Against the ego-centered rationality of Western culture, Arp placed the critical absurdity of Dada, which he came to identify with nature itself,” notes one wall text.

Painted wood

24 ½ x 19 ½ x 3 1/8 in. (62 x 50 x 8 cm)

Collection of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo courtesy Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

That is to say, what happens if we re-write an art history in which the artistic process is in dialog with other worlds and processes external to art communities? What if we understood artistic movements such as Dada through the ways in which trees communicate with one another, for example, or with how seedlings grow? In the calmly elegant space of the Nasher, one might almost miss how radical this proposition is.

The Nature of Arp includes remarkable sculptures: Classical Sculpture (1960), for example, is absolutely brilliant in its form, moving the viewer around it in an ever-changing figure constituted by the most seemingly simple, smoothly rounded gestures. From every direction, the figure morphs unexpectedly, amply rewarding the viewer’s repeated circling. Arp’s cut-out wall relief sculptures are also shown to lovely advantage, as are his explorations of textile, book and zine production, and collage.

But alongside his brilliant formal explorations, there are also moments of real hilarity here, showing Arp’s sensitivity to the strangeness of the human condition. Three Disagreeable Objects on a Face (1930), for example, and Two Thoughts on a Navel (Sculpture in Three Forms) (1932) take Arp’s signature biomorphic forms and make them fantastically weird. The absurdity of Disagreeable emerged, ostensibly, from a dream, and Arp writes:

“i awoke from a deep and dreamless sleep

with disagreeable objects on my face

sophie said they were a big fly a mustache

and a little mandolin

i had no intention whatsoever of removing them

quite the opposite

i remained motionless so that they wouldn’t fall

from my face”

And Sculpture to be Lost in the Forest (Sculpture in Three Forms) (1932) signaled something Arp actually did with his friend Camille Bryen: the two would make and abandon sculptures in the woods, leaving them to chance encounter.

Plaster

Overall, 7 1/2 x 14 1/2 x 11 5/8 in. (19 x 37 x 29.5 cm)

Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, Denmark

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo courtesy of Museum Jorn, Silkeborg.

Apart from making a compelling case for Arp’s lifelong interest in the processes of nature, the exhibition also gives serious attention to Arp’s place within a broader community of artists and collaborators, most notably Sophie Taeuber-Arp, to whom Arp was married for 21 years until her untimely death. “Arp’s impact on his fellow artists surpassed influences based on the use of a shared visual language to encompass concepts that radically redefined the practice of sculpture,” notes one wall text.

And Arp himself would write about the singular importance of community when he described his entrance into Dada in the 19-teens: “It was… like having waited for a long time in the dark and then having been aroused by a loud signal. I stepped forward, and I thought there would be nothing but catcalls. But there were all of you, friends, interested and full of praise.”

In this long-overdue retrospective, it is refreshing to see Arp’s work in new light and to reconsider the way we’ve perhaps been taught to think about him. Here, we find a proposal about art-making as a collective activity, one that grows and flourishes depending upon one’s surroundings, one that is invested in humor and generous engagement with one another, one that is less about the world of art and more about learning from the human and non-human worlds around us. Indeed, we find a whole, rich ecosystem.

—LAURA AUGUST