Hiroyuki Doi, Untitled (detail), 1985, ink on paper, 42 7/8 × 31 1/4 in.

Collection of Paige and Todd Johnson.

© 2016 Hiroyuki Doi; all rights reserved.

On view at the Menil Collection through Oct. 16, As Essential As Dreams: Self-Taught Art from the Collection of Stephanie and John Smither borrows its title from the idea that the desire to create and collect is a deeply rooted human instinct. The exhibition taps into this idea by showcasing selections from the Smither collection that highlight artists whose desire to create led them to develop their practices outside of institutions.

Stephanie and John Smither started their collection in the early 1980s. From there, it grew into a thoughtful holding built upon relationships as much as research and personal aesthetic preferences. As the couple developed their collection, they seem to have been drawn to visionary and autodidactic (self-taught) artists. While these terms are somewhat loosely defined in the art world, the aesthetic practices on display shed light on the connections between the works and the artists.

In particular, viewers can tap into the Smithers’s interest in Surrealism and a form of art that is more raw and intuitive than it is refined. The autodidact might not have exposure to tenured professors who push the development of technical skills, but s/he works to find the most comfortable or accessible means of expression to bring ideas to fruition. This ability to work around tradition and transcend rational thought (particularly by moving beyond reality) was especially valued by the Surrealists.

Because of the self-taught nature of these artists’ practices, the visual aspects of the works in the exhibition vary quite drastically, ranging from drawings and paintings to sculptures and models, but they maintain their connection to one another, each belonging in the space as much as the next. They build from the imagination, the artists’ thoughts or dreams.

21 × 15 1/2 in. Collection of Stephanie and John Smither. © Nek Chand. Photo: Paul Hester.

A trio of sculptural models by Oscar Hadwiger occupy the center of the front space in the gallery. Two are traditionally architectural, displaying a church and a building similar to Seattle’s space needle, while the third, a spiral staircase that ascends to nowhere, dwells more with the imaginary.

Sharing this space—both in the physical and ethereal sense—is a coupling of works by Solange Knopf. Her surreal drawings show the human figure intertwined with the natural world, the cosmos, and semi-mythological figures. Operating in a similar manner, Hiroyuki Doi’s drawings take on biological shapes that simultaneously appear to be drawn out and displaced sections of the Universe.

On the back wall of the gallery is a group of works hung salon-style which includes works by exhibited artists as well as additional artists featured in the Smither collection. The mix of two-dimensional and sculptural works acts as a summary of what the overall collection must be.

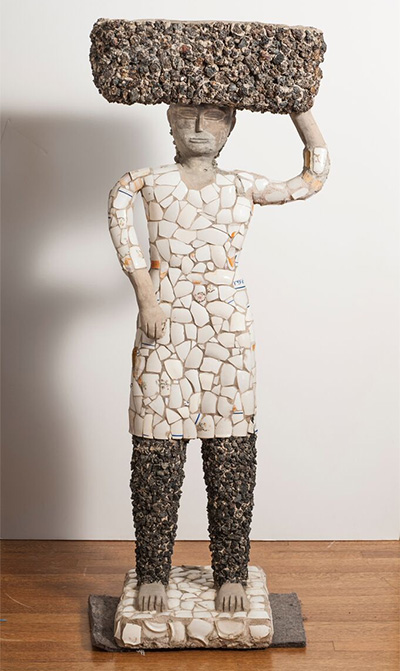

A tiled sculpture of a woman carrying a box on her head shares the space with Howard Finster’s Take Care of Your Body, a circular painting on metal roughly the size of a tire, reads “Take care of your body it is a house for you should take care of your body it will help take care of you life cannot stay here without a body.” Together, the two seem to hint at that underlying philosophy of creating and collecting that drove both the Smither family and the artists they collected.

The Smither collection shows the softer side of patronage, a passionate and intimate ethos less mired in the exploitation of artists for capital gain. By showcasing their approach, the exhibition serves as a strong example of how people, at least those with the money and means, can support artists and the arts.

—MICHAEL MCFADDEN