The Dallas Museum of Art seemed to have known that Matthew Wong was on the cusp of fame before most of the world’s other leading art museums. At the Dallas Art Fair in 2017, they acquired Wong’s oil painting, The West, on a hunch that the emerging artist’s career was on the brink of international recognition. They were right. They were also the only museum that collected the artist’s work during his short lifetime.

This fall, the DMA is presenting Matthew Wong: The Realm of Appearances, the first museum retrospective and US museum exhibition devoted to the late artist, on view Oct. 16 through Feb. 5, 2023.

Wong was in his late 20s and living in Hong Kong when he began experimenting with painting in 2012, then began to pursue it more earnestly the following year. He had no formal art training and took to social media as his “classroom,” connecting and engaging with artists he admired, sharing his works on Facebook, and asking for advice. He was endearingly regarded as the self-professed “newcomer,” not afraid to ask questions as basic as whether he could mix oil and acrylic paint. “Matthew really stood out because he started out not knowing anything and he progressed so quickly every day,” Li says. “He had all these great advisors right at his fingertips.”

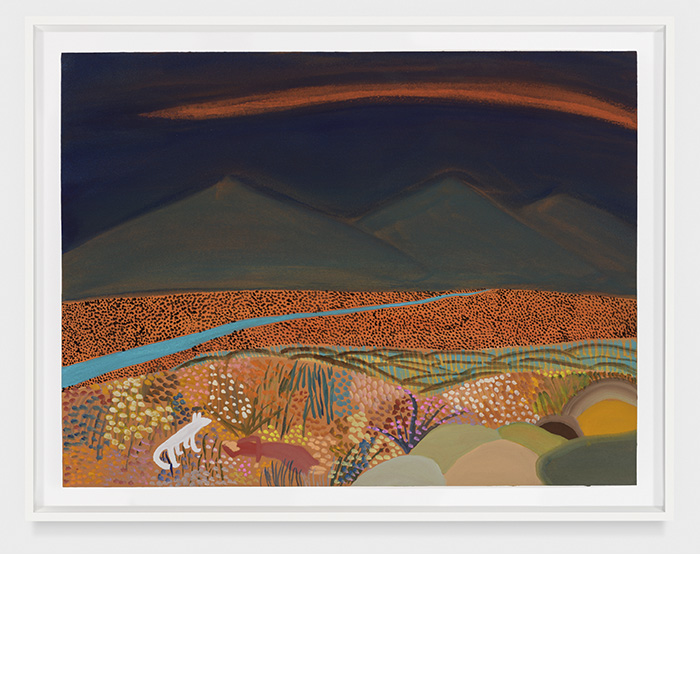

The show then turns to Wong’s return to Canada in 2016, when he begins including human figures in his works before hitting his stride in 2017-2018 by incorporating dense brushstrokes, painted patterns and what he described as “obsessive mark-making.” Some of Wong’s most well-known paintings are contained here, including The West from the DMA’s own collection.

It was in the last two years of his life that Wong began focusing more on seriality, color, and time. “I think in many ways, that’s when he really starts connecting even more with the viewer, where it really resonates with everybody,” Li says. “Everybody has a home or has an idea of home and a lot of his paintings during that time depict the home or interiors of home.” This section of the show includes Wong’s celebrated Blue Series, a collection of monochrome paintings in different tones of blue.

Though the first five galleries are chronological, Li has chosen to make the sixth and final gallery thematic, addressing Wong’s connections with other creative practices. Poetry, for example, was one of his biggest muses. “I think that learning more about his poetry—and his approach to poetry—really helped make sense of a lot of his paintings,” Li says. “How he tried to distill to just the feeling, rather than some place or representation of something.”

1 ⁄6

Matthew Wong, Blue Rain, 2018. Oil on canvas. Collection of KAWS, Promised Gift of KAWS inspired by Julia Chiang to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

2 ⁄6

Matthew Wong, The Performance, 2017. Ink on rice paper. Matthew Wong Foundation. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

3⁄ 6

Matthew Wong, The West, 2017. Oil on canvas. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Fair Foundation Acquisition Fund, 2017.28. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

4 ⁄6

Matthew Wong, Once Upon a Time in the West, 2018. Gouache on paper. Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

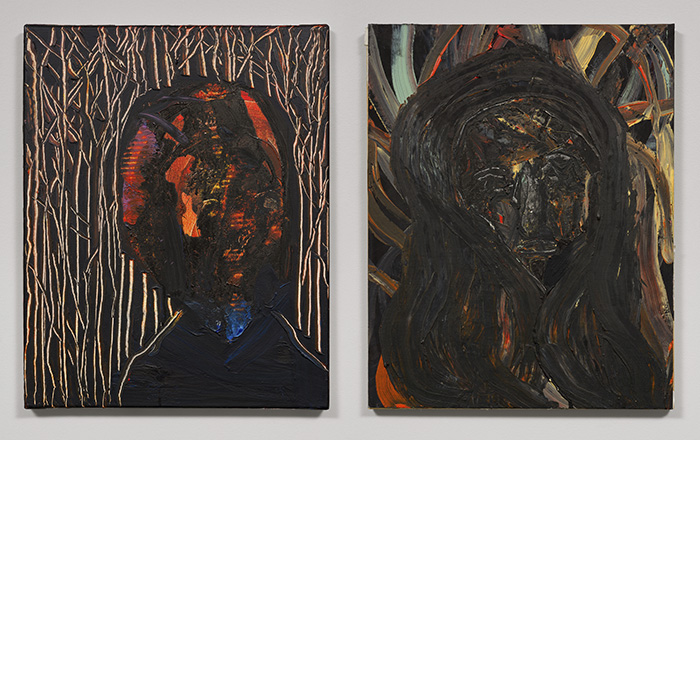

5 ⁄6

Matthew Wong, Banishment from the Garden, 2015. Oil on canvas (left panel), oil on panel (right panel). Matthew Wong Foundation. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

6 ⁄6

Matthew Wong, The Realm of Appearances, 2018. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

—AMY BISHOP