The objects in Gil Rocha’s work—beer cans, hand-painted signs, plastic bags, sun-faded photographs—arrive with their own stories. Once handled, discarded, and left in the margins of daily life, they gather a new weight in his hands. He treats objects like old acquaintances, recognized by their scars, their sun-faded temper, the way they hold a corner of a room. The materials cohere into precise yet provisional constellations.

Back in Laredo, where childhood meant crossing into Nuevo Laredo as casually as moving from one neighborhood to the next, materials arrive charged. Selection follows texture, form, and especially color: the saturated collisions typical of Mexican streets conversing with the American appetite for grays and neutrals.

“Sometimes an object sits with me for years,” Rocha noted. “Other times I know immediately where it belongs.” Family histories thread through these choices, childhood forts made from chairs and towels; a father’s makeshift repairs; a grandfather’s crafts sold to tourists. While training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago braided those instincts with art-historical fluency. What once read as “just trash” becomes, through placement and care, a second chance. The shift in perception is part of the work.

Rocha’s earlier projects placed politics on the surface: Border Patrol as green wolves, migrants as gasping fish, coyotes as shadow figures. The new work turns the political into method and ethic: refuse to discard what society wants to erase; attend to what has been overused; choreograph coexistence among parts that seldom share space.

He spoke of globalized borders, thresholds that shape movement everywhere. The pieces operate at that register. Viewers may first sense a separation, a journey, an inventory of what must be carried or left behind; only later does the geography narrow to the U.S.–Mexico line. Even arrangement becomes metaphor: things that “belong outside” and those that “belong inside” often face each other across a window. What happens when they trade places?

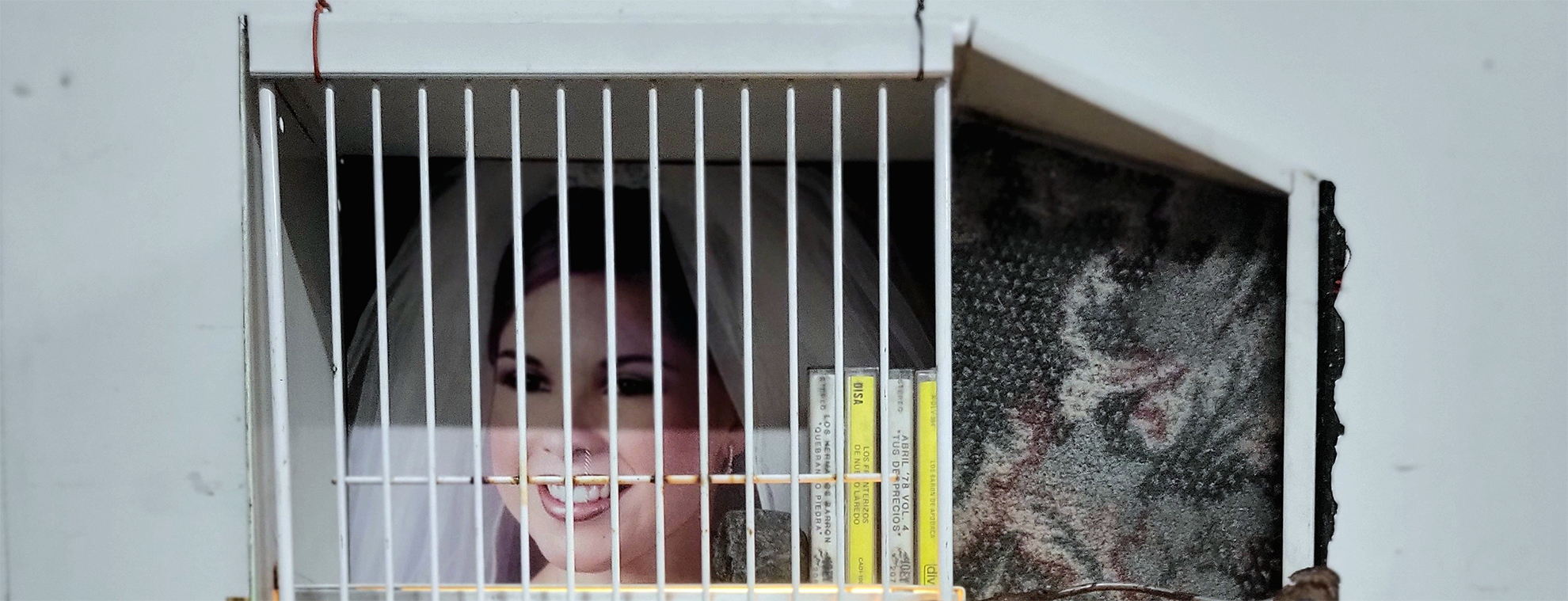

1 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

Between Two Worlds, 2025

Found objects

29” x 28.5” x 7”

Courtesy of the artist.

2 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

Dime, No Te Vayas / Tell Me, Don’t Leave, 2025

Found objects

14.5” x 6.5” x 3”

Courtesy of the artist.

3 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

Casa de Cambio / House of Change or Exchange House, 2024

Found objects

Courtesy of the artist.

4 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

REPARA / REPAIR, 2024

Found objects

46” x 35”

Courtesy of the artist.

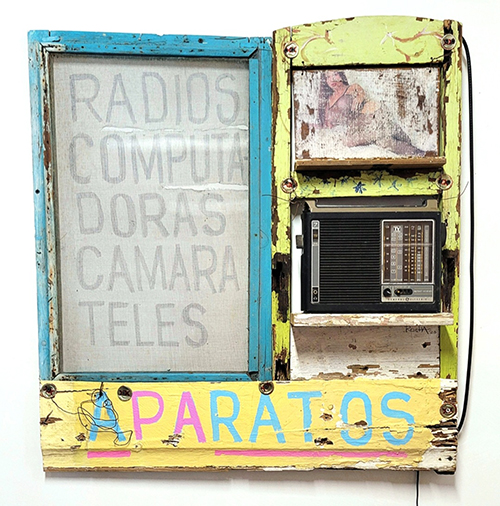

5 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

PA RATOS / FOR MOMENTS, 2023

Found objects

Courtesy of the artist.

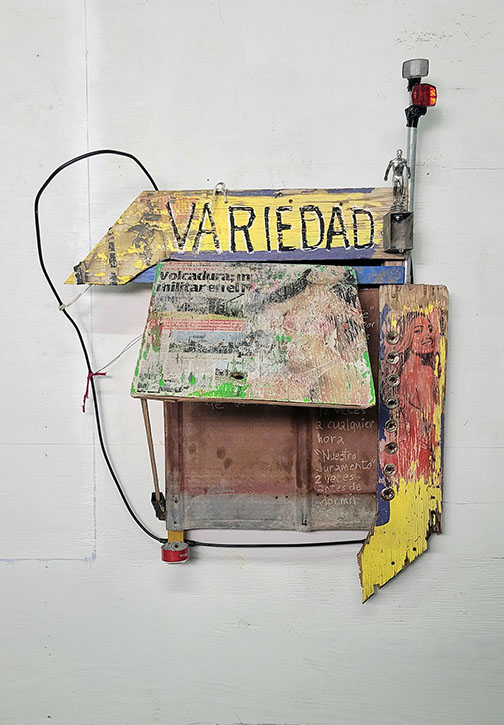

6 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

Variedad / Variety, 2023

Found objects

44” x 34” x 14”

Courtesy of the artist.

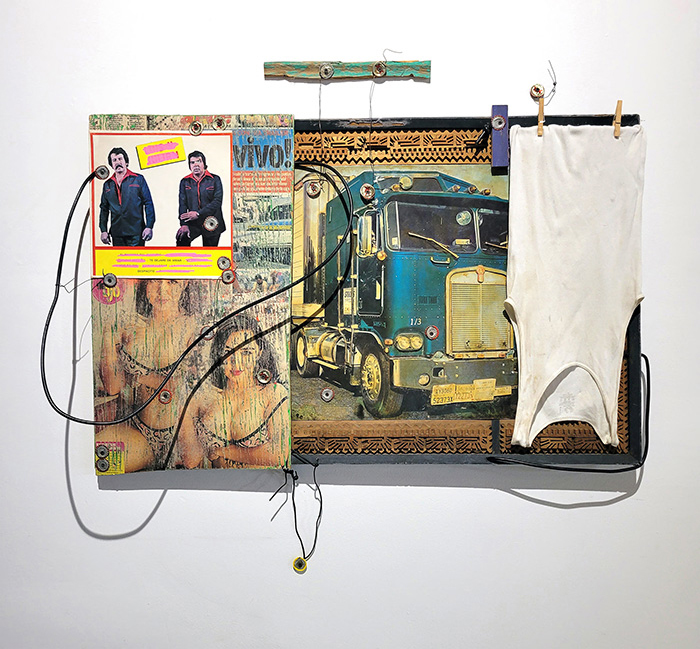

7 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

Te Dejare de Amar - Despacito / I’ll Stop Loving You – Slowly, 2023

Found objects

33” x 51” x 8”

Courtesy of the artist.

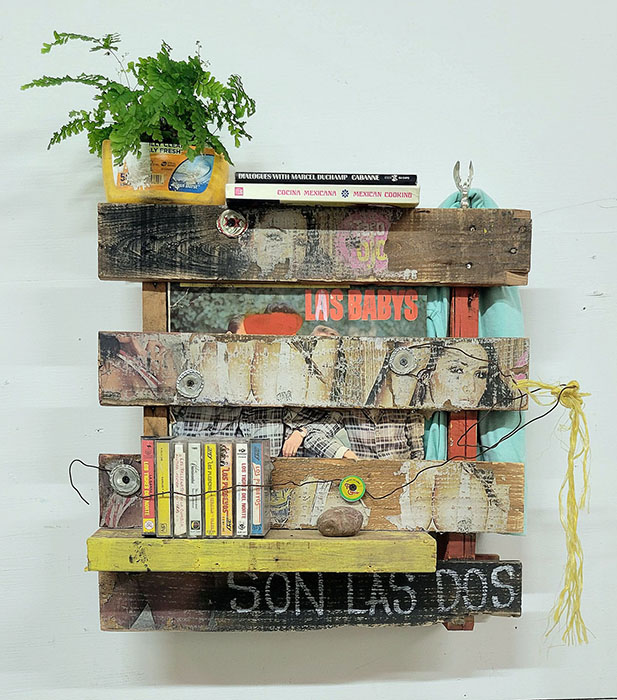

8 ⁄8

Gil Rocha

Son Las Dos / It’s Two or It’s Both of Them, 2023

Found objects

22” x 22” x 10”

Courtesy of the artist.

Language enters as a mischievous current. English, Spanish, and Spanglish ripple through surfaces in short phrases and stray numbers, meaning held open like a door on a windy day. A single underlined tu teases an English ear into hearing “today” while a Spanish speaker reads “you.” Neither reading is wrong; both are invitations.

Formal choices echo this looseness. After noticing too many machined straight lines creeping into constructions, Rocha began cutting angles by hand, an instinct borrowed from earlier collages and, as he joked, “a little Matisse.” One recent piece started as a plant vessel; a salvaged trophy eagle later crowned it, recasting the object as a prize. The question follows: what is being valued: utility, survival, grace under pressure?

Rasquache, an aesthetic rooted in resourcefulness extends beyond aesthetics into psychology in Rocha’s hands. A fixed table leg propped with a napkin works, for a while. “Are we being rasquaches internally?” he asked.

Quick fixes keep the furniture upright but defer the repair. The exhibition’s title points there: mapping memories so tomorrow can be more than a perpetual workaround. Generational time frames the proposition. Bracero-era labor left little room for art beyond song and saleable craft; subsequent decades stabilized conditions; a third generation studies art for its thinking as much as its market.

Rocha describes the past as a scab, evidence of healing that ought not be picked. The artwork becomes a map and a marker. “What is the next generation going to do with it?” he wondered. “That’s the tomorrow I can’t control.”

Curatorial work—exhibitions curated by Rocha such as Picking at Scabs or The Border is a Weapon—loops back into the studio, sharpening the sense of how individual parts speak together as a chorus. The artist still considers backyard shows where sculptures mingle with hoses, grills, and lawn chairs, leaving viewers to decide what is art and what is neighbor.

What emerges is not an argument about the border but a lived grammar of it. Objects once discarded learn to hold themselves differently. They make room for one another. They breathe. In that breathing lies the map: a way from what was carried to what might yet be possible, drawn in the stubborn, generous line of materials given a second chance.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN