A ramp bisects the gallery like a soft fault line. Visitors are asked to sit, to lean, to lay and listen. Sound gathers there, breath, strings, a low thrum emanating, as if the floor itself were remembering. In Zalika Azim: Blood Memories (or a going to ground), the ground is never just ground; it is a witness and a griot, a surface that keeps score of what passes over it and what takes root.

The show, on view at UT’s Visual Arts Center from Oct. 23, 2025 through March 7, 2026, circles those questions through photographs, sound, sculptural forms, a score for performance, and a set of texts that insist on the power of what can’t be seen.

Her pivot from documentary work toward landscape wasn’t about scenery; it was about movement: who gets to move, what movement leaves behind, and how the land records it.

“I’ve been sitting with the idea that the ‘unseen’ experiences of migration might enliven our imaginative possibilities around space,” she said. “How does that inform what it means to belong here and sustain community, especially as so many communities are being disrupted or displaced?”

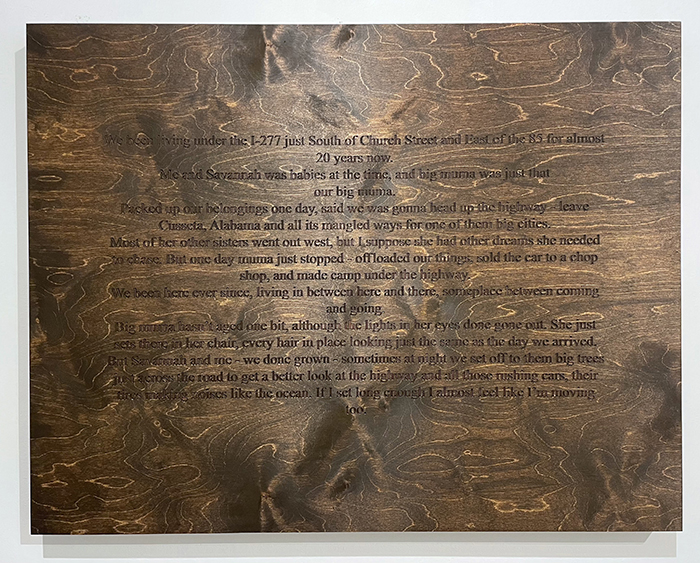

For Azim, the answer is more choreography than map. This logic animates Photographs Not Taken (2021 ongoing), a sequence of text vignettes that stand in for pictures that never were.

“I started to worry my family archive was being read too literally, as autobiography, when I was trying to speak to a larger Black experience,” she explained. “So I sat with the landscapes and the archive together, and these non-linear narratives started to come.”

Early on, she fused text to images via photopolymer plates. “It’s like developing film,” she said. “You expose the plate to light, wash it, and what remains is raised text. We inked the plates and pressed those sentences into the photograph, often in gold.”

1 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Blood Memories (or a going to ground), 2023

Single-channel video, 17:07 minutes

Courtesy of the artist

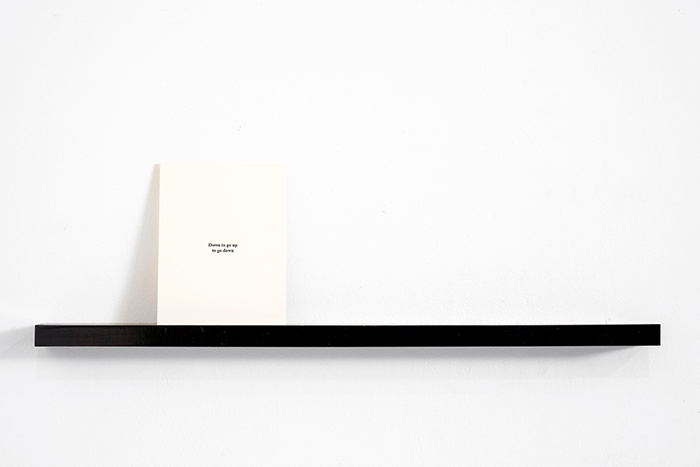

2 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Score I (Studies for Gravity), 2022

Letterpress prints

Courtesy of the artist

3 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Score I (Studies for Gravity) (detail), 2022

Letterpress prints

Courtesy of the artist

4 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Photographs Not Taken (I-277), 2022

Engraved wooden text panels, wood finish, car oil

Courtesy of the artist

5 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Untitled (Austin, Texas), 2025

For the exhibition “Blood Memories (or a going to ground” at the Visual Arts Center, 2025

Courtesy of the artist

Commissioned by the Visual Arts Center and St. Elmo Arts Residency Fellowship, 2023–25

6 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Untitled (Austin, Texas), 2025

For the exhibition “Blood Memories (or a going to ground” at the Visual Arts Center, 2025

Courtesy of the artist

Commissioned by the Visual Arts Center and St. Elmo Arts Residency Fellowship, 2023–25

7 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Untitled (Austin, Texas), 2025

For the exhibition “Blood Memories (or a going to ground” at the Visual Arts Center, 2025

Courtesy of the artist

Commissioned by the Visual Arts Center and St. Elmo Arts Residency Fellowship, 2023–25

8 ⁄8

Zalika Azim

Blood Memories (or a going to ground), 2023

Single-channel video, 17:07 minutes

Courtesy of the artist

The point wasn’t ornament. It was a way to acknowledge gaps between where an event might have happened and the present. Speculation became a tool. Her title nods to Will Steacy’s anthology of the same name.

“I internalized his prompt,” she added. “What about the images families don’t hang in the living room because they’re too hard to talk about?”

The exhibition’s title work, Blood Memories (or a going to ground) (2023-25), stretches that ethic into space and time. A quiet video unfolds at the speed of weather, while Score I (Studies for Gravity) (2022) lays out letterpress instructions that read like mantras: down to go up, up to go down.

“I was talking to a ballet instructor about how you can use force to gain buoyancy,” Azim recalled. “That idea of spending gravity instead of submitting to it became a score, an invitation to think about repetition, endurance, ritual.”

If gravity is the rule, double Dutch is the counter-rule. During lockdown, when gathering could only happen outdoors, she watched jump ropes cut rhythms into public parks.

“It rewired how I was thinking,” she said. “Migration opened up to movement, and movement opened to embodied knowledge. The gesture of the jump became a metaphor for this moment; why return to the ground when you know you will? What does that say about endurance?”

Out of that came kinetic rope sculptures and works on paper that index motion without depicting it, pieces that listen as much as they loop. Austin itself becomes a score in newly commissioned photographs and site-responsive sculptures tracing Black placemaking in the city’s freedmen towns.

“Texas has a robust database,” she noted, “but there’s still so much unknown. I’ve been going to the sites where communities once existed, making pictures, reading the landscape for what the archive doesn’t show.”

“They invite a particular kind of bodily engagement,” she said. “Not a spectacle, more like breath work. A way of grounding.”

Throughout, the body is implied rather than centered.

“Moving away from documentary, I’ve stayed with landscape,” she said. “You might see evidence of presence, but not people. The body is suggested, through voice, or a kind of embodied movement.”

That stance opens the work to collective time. Azim spoke of how she grew up in Brooklyn’s Bed-Stuy neighborhood and moved around the U.S., explaining that she could see how government policy disrupts communities, but you also see regeneration. People endure, pick up, build anew. Each time, there’s something learned.

Collaboration is one of her methods for learning. The gallery’s ramp doubles as a stage for a new performance crafted with UT students, staff, and faculty near the close of the run; when it isn’t a stage, it’s a listening station for a sound work conceived with Black and brown improvisers in Omaha.

“We spent hours sharing research, personal histories,” Azim said. “I asked: if we made something intended to be heard fifty or a hundred years from now, what would it sound like? How would we talk to those listeners about the places that made us?”

Earlier, in Los Angeles, she worked with movement artist Jennifer Harge while reading Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive. Thinking from a future in which she is already an ancestor changed how she approached land and place she said. The future here isn’t chrome; it’s a mode of attention.

“That discovery shifted me,” she said. “I spent three years with those photographs, sequencing them, sitting with family members as they told stories that sometimes negated one another.”

It brought up tensions of time and remembrance, and she continues to sort it all out. But it taught her to enter a photograph knowing how much exists outside the frame. That lesson reverberates in Blood Memories. The texts speak in fragments; the rope’s shadow stands in for a crowd; a footpath becomes a ledger.

“The viewer is a collaborator,” she added. “You complete the circuit.”

The show’s title marries inheritance to tactic. “Blood memory feels like what we carry without being told,” Azim said. “Going to ground is both protection and practice. I’m asking whether an artwork can hold both—whether a score or a text can be a place to regroup.” The ramp answers by gathering bodies at rest and at the edge of motion. The score answers by teaching lift through descent. The photographs answer by listening for what lingers in the grass.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN