Stories first live in the body. They prickle across the skin as goosebumps, catch in the throat as a gasp, and move along a family line, changing slightly with each retelling. A good story lingers, reshaping memory and place so that a river, a vacant lot, or a patch of brush never feels quite the same again.

Those stories begin in Laredo, Texas, in a large extended family of primos and primas, tías and tíos. Oral storytelling was a favorite ritual, especially at carne asadas when everyone drifted toward the fire and the sky turned dark blue. Relatives who had passed returned in anecdotes about dreams, apparitions, and uncanny encounters; nothing was written down, the stories lived in voices and gestures. Later, as Raquel left for graduate school in San Antonio and her grandfather’s health declined, that world felt both close and distant. She turned her practice toward her family to “reconnect with it and celebrate it,” and found that the more specific she became, the more viewers recognized their own families’ legends and sleepover scares.

Raquel grew up in a family of hunters, where deer in the backyard were a familiar sight at gatherings. One day, as a small child, she walked outside to find her grandfather cleaning a doe, blood pouring into a bucket, organs and skin laid out nearby. Instead of shooing her away, he drew her in. “He said, ‘This deer lost its life because of us. We’re going to take its meat and its skin and we’re going to eat because this deer died. So say thank you to the deer,’” she recalled. “He told me, ‘Everything we don’t use, we bury and give back to the earth.’” The memory is visceral, but it never hardened into horror. It became an early lesson that taking requires acknowledgment, that life and death are bound together.

1 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel in her studio. Photo by Olga Maya, Courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

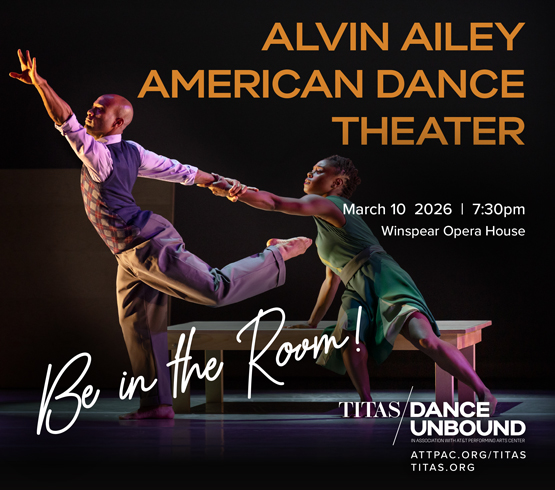

2 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel, Grandpa’s Magic, 2025. Yarn, ribbon, felt, vintage beads, and charms on monks cloth and felt, 72 x 59 in. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

3 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel, Dad’s Lantern, 2025. Wool, polyfiber, felt, polyfill, cotton, buttons and fabric trim, 33 x 11 x 5 in. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

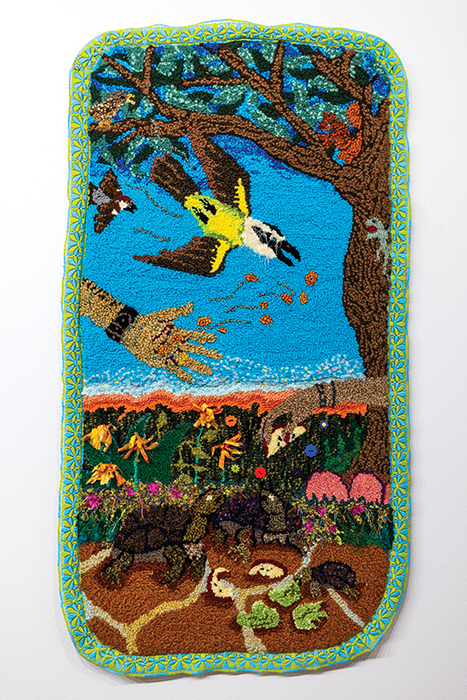

4 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel, Mom and Dad’s Morning Prayers, 2024. Yarn, ribbon, and silk on monks cloth with fabric trim, thread, buttons and felt, 56 x 30. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

5 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel, Estúpida’s Wisdom, 2025. Yarn, felt, ribbon, secondhand charms, thread, and buttons on monks cloth, 33 x 24 in. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

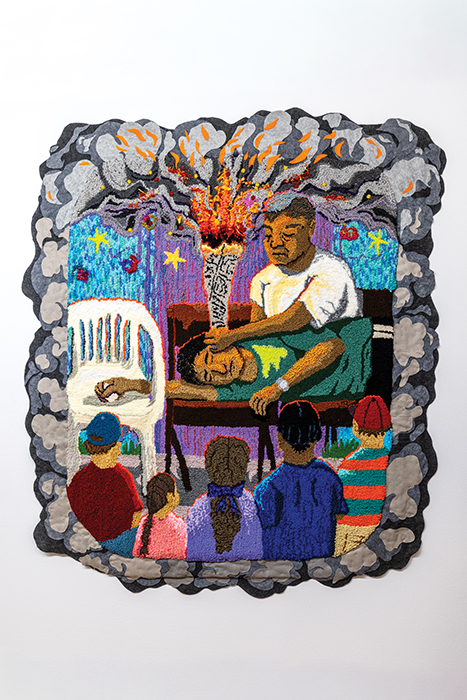

6 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel, Psalms of My Youth, 2023. Yarn, embroidery thread, and glass beads on monks cloth and felt, 72 x 59 in. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

7 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

8 ⁄8

Angelica Raquel, Howl Together, 2025. Wool, polyfiber, felt, thread, and vintage charms (Activated with needle - felt imagery from community workshops to be held in tandem with the exhibition). Dimensions variable. Photo by Chris Stolze, courtesy of McNay Art Museum.

Years later, that memory returned with new force. Raquel wanted to make it into an artwork, but painting alone felt too flat. Around 2018–2019 she discovered needle felting and rug-hooking and taught herself both in order to realize a single vision: “a large three-dimensional deer that was as white as a ghost, because it needed to be a ghost. It was a memory.” The sculpture she created shows the animal in two states. On one side, the deer lies on a tall rug-hooked pasture, head proudly lifted, forcing viewers to look up. Walking around it, they encounter a second head resting softly, the flank opened to reveal felted innards. “Though visceral and intense, it taught me that life and death are one and the same.” That ghost-deer became the hinge of her practice and opened the path for fiber to become her primary language.

Mystic Threads spreads outward into familial stories, regional legends, and invented myths. Many of the narratives draw from borderland folklore pressed gently but firmly into contemporary shape. La Llorona, whose wail trails along rivers and roads from Texas to California, is one of the more daunting figures Raquel has taken on. In a recent tapestry, she approaches La Llorona as a lens on abandonment, mental illness, and social neglect. “I wanted to explore abandonment, mental illness, and the lack of societal or cultural resources for women in horrible situations,” she explained, “and how that affects someone. I wanted to shift the narrative so it becomes a reflection of us as a society and culture, focusing on the sadness and tragedy of it, rather than ‘you must be a good wife or a good woman no matter what.’” The ghost becomes less a monster than a mirror.

These pieces fold in materials associated with friendship and play—bracelet cords, beads, small charms—alongside felt and textile. Across the show, certain symbols repeat: stars, hands, eyes, sometimes hidden, sometimes overt. “The star and the hand are really potent symbols in my work,” Raquel noted. “The hand can be like a curse or a spirit that’s on you, even if it’s not actually there. The eye shows up too.” She pushes this symbolism to the edges of her works, into handmade trims and engraved frames that hold extra fragments of narrative. A single piece about a linear story can only depict one moment; the borders become space for everything that spills over, like a story bleeding into the margins.

Animals move through this universe as emotional proxies and guardians. In recent years, Raquel has given them an even more overt emotional charge. “They come from a knee-jerk emotional reaction to hearing about so much pain and sadness from incredible women I know, their experiences with partners, families, all of that,” she stated. The resulting works imagine ways of holding that pain: a doe wrapped protectively around a body, an owl watching with almost uncomfortable vigilance, foxes and jackrabbits caught between flight and stillness. “The animals can stand in for us, people I’m thinking about individually, or for parts of ourselves,” she explained. “I connect with what each animal can offer: toughness, strength in struggle, aloofness, mystery. Those qualities can become strengths we harness.” Underneath, a quiet conviction hums: gentle and tender never die.

Angelica Raquel: Mystic Threads, organized by Liz Paris, Curator of Collections/Collections Manager, and Lauren Thompson, Curator of Exhibitions, unfolds as a constellation of such presences—deer, coyotes, owls, girls at sleepovers, grandparents by the fire. The stories they carry do not resolve into a single moral. They hang in the space the way a good tale does after the flames burn low: a warning not to whistle at night, the memory of saying thank you to a deer, the sight of a blue coyote cloaked in many people’s symbols. At its core, the exhibition offers an invitation to notice the stories that have quietly shaped one’s own life, and to imagine how they might look if given the weight of wool and thread, held in the open, and shared in the circle of a communal, mystic fire.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN