“He’s a wanderer by nature and upbringing,” describes Ann Dumas, consulting curator for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s fall blockbuster exhibition, Gauguin in the World, on view Nov. 3, 2024-Feb. 16, 2025.

Originally organized by independent curator Henri Loyrette, former director of the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, the exhibition debuted at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra with a slightly different name: Gauguin’s World. Thanks in part to the MFAH and director Gary Tinterow’s previous collaborations with Loyrette and the NGA, Houston is the only U.S museum to present this expansive exhibition showcasing 150 Gauguin’s works, including paintings, sculptures, prints and writings.

“There have been many great Gauguin exhibitions in the past, particularly in the last 15 years or so, but for those exhibitions all these kinds of controversial, polemical sides to Gauguin weren’t really discussed,” says Dumas. “Since then we’ve had the MeToo movements and there’s a great deal of anti-colonialism feeling around. Gauguin is right in the storm of all these debates. You can’t really do anything on Gauguin now without at least acknowledging that side of him.”

Dumas finds it somewhat “daunting” to mount a Gauguin exhibition amidst the “storm,” but as controversial as we might find Gauguin now, not many will debate the richness of his work and his lasting influence on the art world.

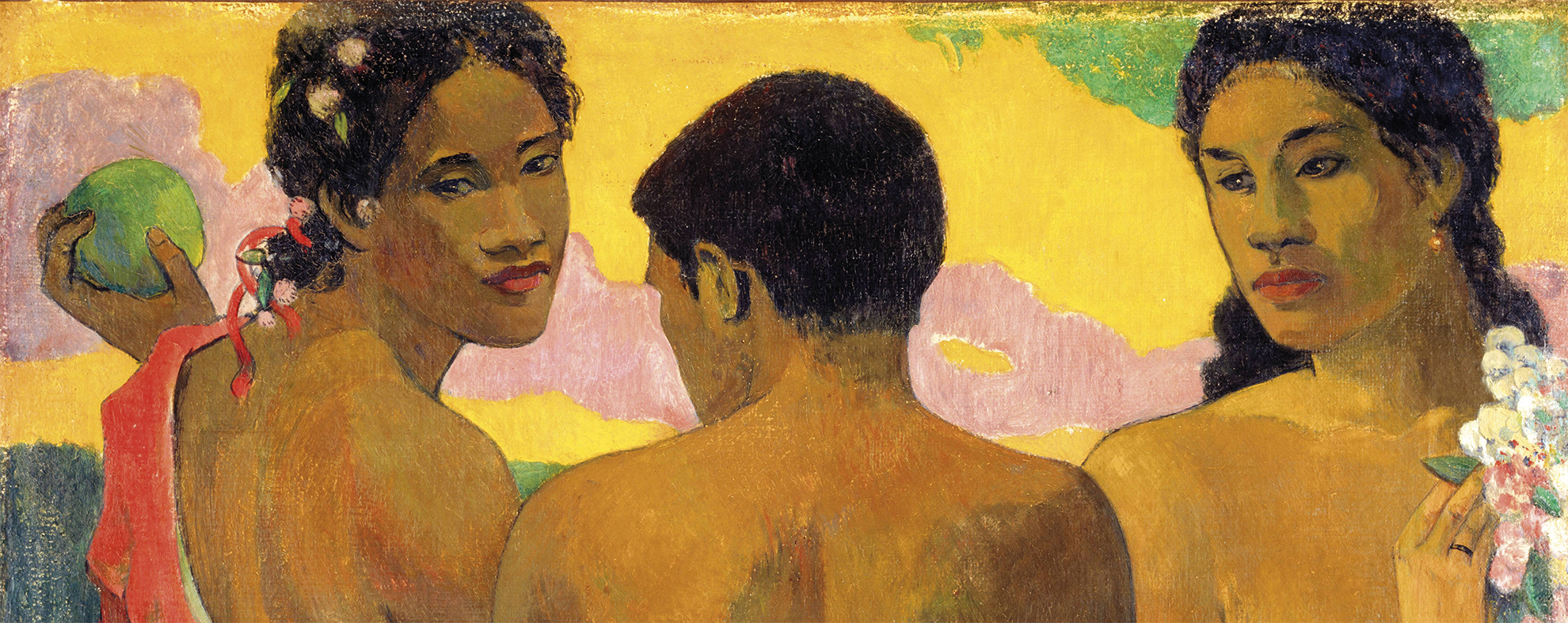

1 ⁄6

Paul Gauguin, Femmes de Tahiti (Tahitian Women), 1891, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo © TMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

2 ⁄6

Paul Gauguin, Vase Decorated with a Fishing Scene, 1886, coffee-colored unglazed stoneware, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource. NY

3 ⁄6

Paul Gauguin, Portrait de Madeleine Bernard (Portrait of Madeleine Bernard), 1888, oil on canvas, Musée de Peinture et de Scupture, Grenoble, France. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

4 ⁄6

Paul Gauguin, Nature morte au profil de Laval (Still Life with Profile of Laval), 1886, oil on canvas, Indianapolis Museum of Art.

5 ⁄6

Paul Gauguin, U‘u (Club), 19th century, wood and vegetable fiber, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 2008.

6 ⁄6

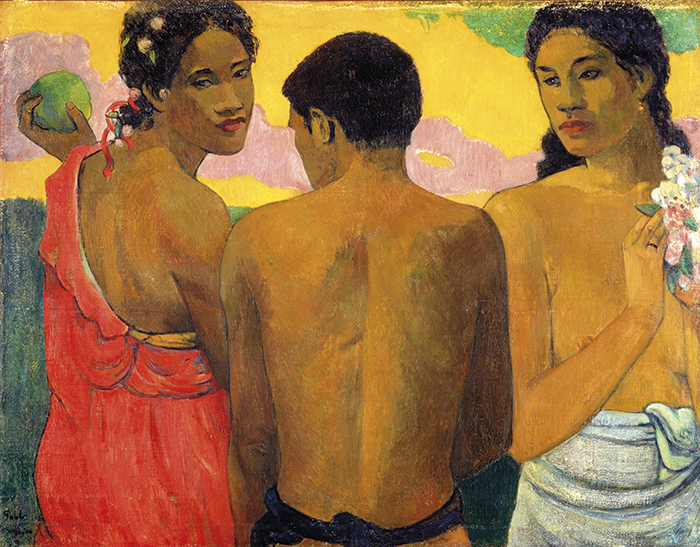

Paul Gauguin, Trois tahitiens (Three Tahitians), 1899, oil on canvas, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, presented by Sir Alexander Maitland in memory of his wife Rosalind 1960.

Dumas is organizing the galleries mostly chronologically, but speaking with her it becomes apparent arranging the art by years also necessitates arranging the art by place.

The exhibition begins with an early self-portrait, one of about half a dozen that collectively give us Gauguin’s changing views on Gauguin. Along the way, we wander with him from the beginning of his career in Paris heavily influenced by Impressionism. We follow him to Brittany, and see his breaking with Impressionism’s ideals and its focus on direct observation and capturing the fleeting moment. His colors brighten and he becomes much more interested in imagination and trying to catch the spirit of a place.

“He’s not a storyteller. He’s interested in creating a mood and a mystery,” describes Dumas of his work in Brittany and later in Tahiti, as he becomes influenced by the literary Symbolism movement.

The exhibition also includes two works he painted while living with Vincent Van Gogh in Arles, France. Dumas notes that while Van Gogh admired Gauguin, in the end, neither their painting philosophies nor personalities meshed very well.

“I think he’s completely bowled over by the beauty of the place, the landscape, these great mountains, the beautiful light and tropical vegetation,” explains Dumas, but notes he was also disappointed at how many French people had arrived before him.

These paintings and prints allow us to see what Gauguin saw, though filtered through his own obsessions and ideas. He became fascinated by Tahitian culture, particularly its religion and rituals, which he tried to depict in some of his paintings, like Mata mua (In Olden Times), and its scene of Tahitian women worshiping near a statue of a moon goddess.

“A lot of that kind of culture was stamped out by the Christian missionaries, and Gauguin very much resented it. He hated the way western missionaries had destroyed this incredibly vivid Polynesian culture. He tries to recapture that in his art and especially in the very vigorous wood cuts,” remarks Dumas, while referencing some of the prints and woodcuts included in the show.

In the Tahiti galleries, we can see superb examples of Gauguin’s interest in creating mood and mystery, as opposed to naturalistic renderings. One of Dumas’s favorite works from this period is, Te raau rahi (The Large Tree). The painting portrays a deep stillness as a scattering of Tahitian women rest in the shade of trees and in the entrance of a bamboo hut.

Dumas says he found a different reality in Tahiti and the Marquesas, but there was already a “different reality in his head.”

“His works are so rich because he folds all these traditions into them in such an interesting way. Also his incredible technical diversity and skill, his experimental approach to all sorts of material is amazing really.”

In the last galleries of Gauguin in the World we’ll find a final series of prints, a late, stripped-down self-portrait and a painting of a snowy landscape of Brittany, which he apparently painted in the heat of the Marquesas. Even at his own personal world’s end, Gauguin seemed to wander on.

—TARRA GAINES