Driving alone through the middle of the country, spanning nine states and more than 4,000 miles, Dallas-based artist, cultural critic, and social activist Colette Copeland spent three summers visiting the numerous sites where Jesse James lived and outlawed, filming on location throughout her performative journey. The result is a 22-channel video installation which will be on view June 4-August 20 at the Old Jail Art Center (OJAC) in Albany, TX as part of its Cell Series, a long-standing series of exhibitions featuring the works of contemporary Texas artists.

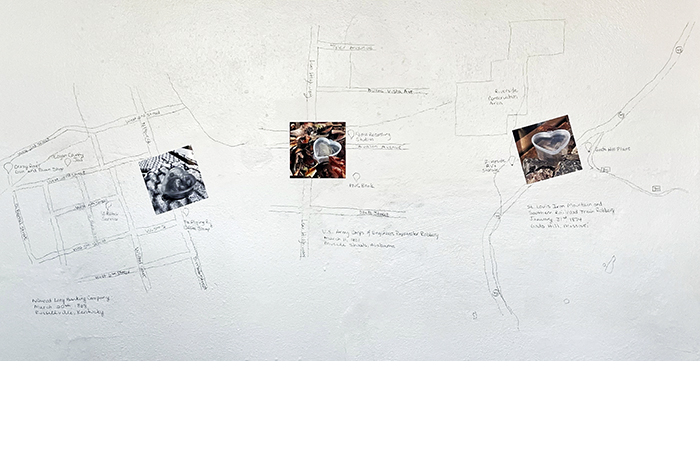

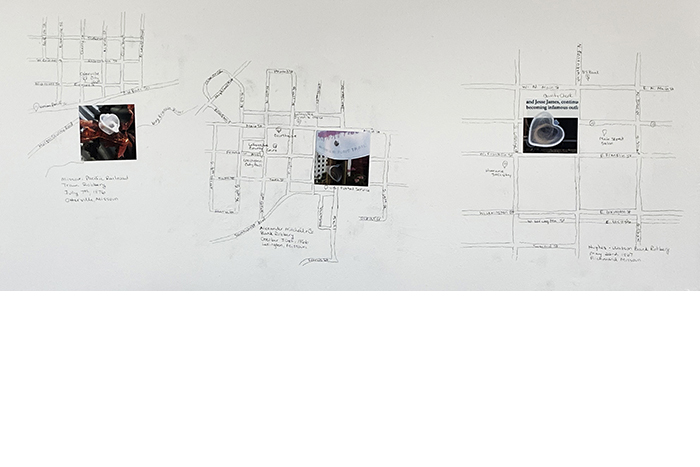

The family connection to the legendary criminal is convoluted. Copeland’s great- great-grandmother’s second husband was a first cousin to Jesse James. Then her great grandmother (daughter of the third husband) married her stepbrother (son of the second husband), continuing the James lineage. Copeland left a lock of her hair in a clear, heart-shaped box at each of the sites James outlawed. Photos documenting these DNA offerings will be displayed along the walls of the cell, mapped out in its actual geographic location.

Meanwhile, at Jody Klotz Fine Art (June 7-August 31) in Abilene, TX, viewers can contemplate another aspect of Copeland’s My Jesse James Adventure through two series of etchings that reflect the sheer volume and depth of the research the artist undertook for this project. The solar plate etchings include images from various sites of interest on Copeland’s pilgrimage, as well as images of vintage movie posters and other kitsch the artist discovered down this or that rabbit hole of Jesse James pop lore. As part of her research, Copeland watched movies with titles such as Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter and Jesse James’ Women. “As you can imagine,” she chuckles, “they were horrific.”

“One of the things I was interested in was how James has become commodified and is still commodified today.” Copeland cites the Jesse James Wax Museum in Stanton, MO as another example. “It’s a bizarre place where you can see lots of James memorabilia, and it was dedicated to the theory that James faked his death and moved to Granbury, TX where he lived to be over 100 years old.”

Despite the overt references to her blood connection with Jesse James, Copeland’s project is not really about her personal connection with the man. “It’s my origin point,” says Copeland. “But the piece is really about so many other things—how we mythologize criminals, having conversations about how history is recorded, having conversations about contemporary issues of gun violence, race, and fake news.”

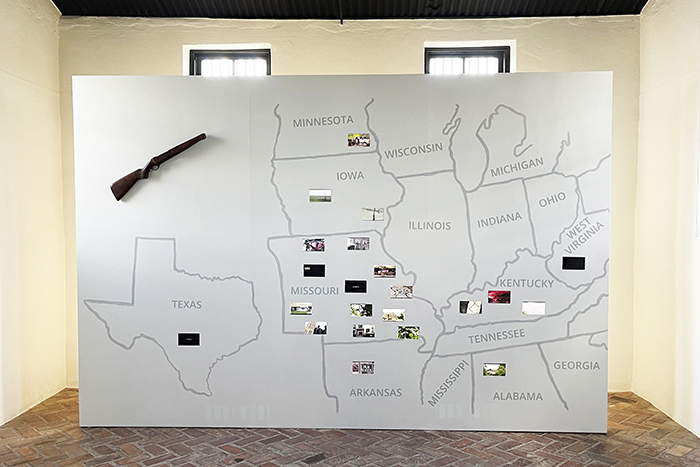

Viewers glimpse potent parallels between the past and the present throughout the various installations in both exhibits. In the 22-channel video installation, laid out on a somewhat skewed map of the United States, silent moving images are often layered or composited. Long dissolves and subtle effects shift the viewer’s visual plane. “In my works that deal with history, I’m looking at collapsing time,” explains Copeland. She is filming in the present, but referencing history through this visual strategy of layering. “I want the viewer to enter into that world of both the past and the present, and glimpse the possibility for what the future may hold.”

A palimpsest of memory, a play on time, a questioning of history as truth—Copeland invites the viewer to contemplate historical and contemporary issues through a different lens. And sometimes current events have a way of providing new perspectives in unexpected ways.

Copeland did not think her project was about race until she went to Cabela’s to look for a gun scope right around the time George Floyd was murdered. She had wanted visitors to be able to look at the videos through a gun scope. “When you look through a gun scope, you have tunnel vision and you are looking at your subject through crosshairs. I wanted people to think about their relationship with firearms and what it means to literally target something. And beyond that, what happens when our peripheral vision has been erased and we can no longer see something from a full perspective.” When she stepped into Cabela’s, there were huge lines all around the store of people waiting to buy guns. “That was when the issue of race became salient for me,” recalls Copeland, “seeing white men waiting to buy guns as a response to the George Floyd protests.”

1 ⁄10

Installation view, Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Jody Klotz Fine Art.

2 ⁄10

Installation view, Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Jody Klotz Fine Art.

3 ⁄10

Installation view, Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Jody Klotz Fine Art.

4 ⁄10

Installation view, Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Jody Klotz Fine Art.

5 ⁄10

Installation view, Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Jody Klotz Fine Art.

6 ⁄10

Installation view, Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Jody Klotz Fine Art.

7 ⁄10

Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, 22 channel video installation with an audio guide featuring Ike Duncan and original musical score by Dallin B. Peacock. Photo courtesy of the artist.

8 ⁄10

Detail, Cell 3: Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, photographs of hair offerings and wall drawings mapping geographic locations of James' Gang robberies. Russellville, MO, Muscle Shoals, AL & Gads Hill, MO. Photo courtesy of the artist.

9 ⁄10

Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, photographs of hair offerings and wall drawings mapping geographic locations of James' Gang robberies. Otterville, Lexington & Richmond, Missouri. Photo courtesy of the artist.

10 ⁄10

Colette Copeland, My Jesse James Adventure, Lock of Hair. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jesse James fought for the Confederacy and outlawed in the years immediately following the Civil War. Through her research, Copeland began to understand the motivation that drove James to his crimes. “I’m not condoning his actions,” Copeland asserts. “James was 16 when he joined the guerilla army in the swing state of Missouri. He and his brother knew how to do two things well, shoot and ride.” After the Civil War, many former Confederate soldiers were unable to find work or get a loan from the bank in Union-controlled Missouri. James turned to the things he knew how to do best when he couldn’t make it as a farmer.

Always looking for parallels between the past and present, Copeland thought of the many veterans who had been her students at Collin College. She has seen first-hand how difficult it is for these veterans to assimilate back into civilian life, especially if they had been in a war zone. “Those students who had been part of the Iraq War came back feeling like they’re not qualified to do anything. They are trained to protect themselves and protect us, but finding a regular job doesn’t usually work out very well.”

There are two components of the project that will be part of both sites of the Jesse James exhibition. “I wanted to create some synergy and also have something tangible that would carry through besides the subject of James,” says Copeland. While the Ike Duncan audio guide gives visitors access to the history of what happened at each site, the original music score by composer Dallin D. Peacock plays an integral part in Copeland’s conceptual vision of the installations.

The performative journey took Copeland to many places she would have never visited otherwise. “Some were a little scary,” admits Copeland. She found out Huntington, WV was the drug death capital of the U.S. and had the highest per capita rate of opioid addicts. In St. Joseph, MO, she unknowingly booked an Airbnb next to a park where the meth addicts congregated. Despite the hard times some of these towns face, Copeland notes that the sense of pride to keep their history in place is strong.

There are no defining statements here. My Jesse James Adventure poses questions that prompt conversations. “I had a student ask me if I was proud to be related to Jesse James and why I would spend all this time to show this,” recalls Copeland. “I think about the legacy of prejudice and injustice on both a personal and collective level, questioning my own family and cultural inheritance. I can’t fix things, but as an artist I can engage the public and bring about awareness. By presenting my story through the lens of an artist, I can bear witness and hopefully be a catalyst for dialogue about uncomfortable subjects. It’s important we don’t hide things away and we don’t shy away from difficult conversations.”

—SHERRY CHENG