In 1992, two young local artists, Robert Herrera and Oscar Cortez, began transforming a 700-square foot wall section around the Holly Street Power Plant in East Austin into a spray-painted story of identity, pride, and community. Though that enormous commissioned painting, For La Raza, would begin to fade within its first few years of existence, the mural easily became an art icon of the neighborhood and city. Now 26 years later, this celebration of Chicano heritage has received a composition and color resurrection. Restored to Austin in all its glory, the mural has also brought one of its creators full circle in his artistic life.

I recently talked with Herrera about the process of restoring this visual staple of the Holly Shores neighborhood, but also about how the work helped bring him back to his artistic calling. Originally commissioned by Austin Energy, For La Raza depicts images of a Spanish-mustached Aztec sun god, the Earth, American and Mexican flags and a stone fist becoming flesh, all bordered by two symbols of power and beauty, the faces of an Aztec man and woman.

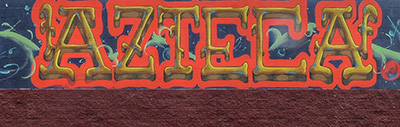

Of all the images and the graffiti-style lettering of the word “Azteca,” it is the fist that seems to represent one of the essential messages of the mural for Herrera.

“The fist is an actual thought in stone coming to life and it turns to flesh,” describes Herrera. “The fist was self-awareness, learning your heritage, realizing self-worth and self-determination, trying to paint something positive. When we painted it the first time there was still a lot of gang-banging going on. The whole deal with the mural was trying to show a positive image of being Mexican-American.”

Even though the images and meaning of the mural continued to resonate, the paint itself did not stand the test of time. As the power plant was taken over by the city and then shut down, the mural faded while some of its sections painted over and “tagged” with graffiti. Perhaps the mural became an example of artist and creation changing together because For La Raza was also one of the last works Herrera painted before putting aside his brush and spray can for two decades.

“Every now and then I would look at it, but it was kind of a chapter that I closed. I stopped painting to raise a family,” explains the licensed electrician. Years later, his younger children didn’t even know much of Herrera’s life as an artist.

“The first times we drove by the little ones didn’t realize I had painted it. They just saw an old faded painting. They kept playing on their phones.”

After the city decommissioned the power plant and turned the area turned into parkland, there also came a call to save some of the neighborhood art. As a phase of the Holly Shores Master Plan, the Parks and Recreation Department worked with Art in Public Places and the community to identify historic murals at the power plant in need of restoration. Arte Texas, an organization of artists including Herrera and Cortez was founded by Bertha Delgado to save the mural; it was commissioned to develop a restoration plan. With so much wear and damage done to the mural over the decades, the plan called for the original artists to repaint the entire mural, this time using acrylic paint, so the vivid colors might easily last beyond another 30 years.

“We didn’t see this far down the road,” says Herrera looking back at the mural’s first incarnation. “We didn’t see almost 30 years later. We didn’t think the mural would last this long or the wall be there that long. That was a surprise.”

The artists reworked several of the images, making the faces and lettering more distinct and giving “Azteca” the Earth, flags, and sun a vibrant and almost kinetic cosmic background. Though Herrera says it wasn’t entirely intentional, that fist changing from rock to flesh now also resembles an asteroid or comet floating through space.

“It’s an eternal struggle, that’s why it’s in motion like that,” describes Herrera. “This is reasserting the dominance of where you come from. We don’t need to go across the border. We don’t need to leave our land. This was Mexico for my great, great grandfather. I literally don’t come from anywhere else.”

For La Raza also brought Herrera back to his art, and he’s now working on canvas paintings and planning other mural projects.

“I find myself 360 degrees. I went off to do something different, leaving politics and murals behind. Now I find myself engaged with some of the same people that I stopped talking to almost 30 years ago. What’s sad is finding a lot of the same problems still exist.”

Beyond his personal artistic rejuvenation, the restoration also became a celebration for the community and a chance to educate the next generation. Early in the process, Arte Texas reached out to area schools and soon high school, middle and even a few elementary school students were enlisted to contribute to the project.

The students learned about culture, history, Aztec self-determination, and a lot about painting.

“I would like to think they learned a little bit about their culture and the joy of painting, being creative. You have to be creative. It opens doors in the mind,” explains Herrera. “I hope by working on the mural, it becomes part of their life. It’s part of their history and they hold on to it. I hope they watch over it after I’m gone.”

—TARRA GAINES