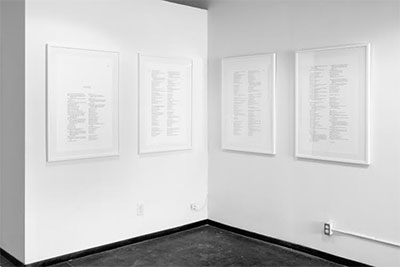

Sherwin Rivera Tibayan, Index. Courtesy the artist and Reading Room.

Sherwin Rivera Tibayan at the Reading Room

Photographer and conceptual artist Sherwin Rivera Tibayan’s practice takes photography as both its subject and its medium, but the small, contemplative exhibition Index, which recently closed at Dallas’ Reading Room, resonates far beyond his primary medium.

The exhibition was simple, consisting of just four framed pages of an index of Susan Sontag’s canonical text, On Photography. The piece was born out of need: an index to Sontag’s reference-laden collection did not previously exist so, as Tibayan was reading, he created a Chicago Manual of Style-approved index of the work’s contents. The piece was presented at the Reading Room as a conceptual artwork, framed and hung on a gallery wall, consisting of text, which amounted to a history (albeit reductive) of photography and 20th century critical and popular thought and, more importantly, an opportunity to critically reconsider both.

Tibayan, an Austin-based artist, is interested in photography, yes, but less in photography as a medium than in our relationship to images and how we culturally conceive of the role of the photograph. His work has ranged from a photographic exploration of wires, in particular, our ubiquitous apple earbuds (in a 21st century spin on Stieglitz’s symbolist work of the 20s and 30s); to “Marks of Indifference,” in which Tibayan photocopied and marked through the text of Jeff Wall’s widely read essay on photography, before printing the marked-up copies again as an art book, critiquing the desirability and fetishization of both images and critical writing on photography as he did so, in an effort to, in the words of Tibayan, “locate a space between the legible and the obscured, between reverence and refusal.”

With much of his work Tibayan is plumbing the depths of over a century of photographic history and theory and attempting to forge an understanding of what it all means today, specifically how theory as well as new technologies have affected our relationship to the image.

With much of his work Tibayan is plumbing the depths of over a century of photographic history and theory and attempting to forge an understanding of what it all means today, specifically how theory as well as new technologies have affected our relationship to the image.

He’s one of a number of artists working today who have realized photography’s potential, in particular, to serve as a tool for exploring how our conceptualizations of history and time have changed in the postmodern world; utilizing it and its paradoxical ability to capture and create history at the same time as it obscures and clouds it, to invite viewers to critically reexamine the position of authority we’ve collectively granted to the photograph.

Tibayan’s work is predominantly consumed with the history of photography and photography students and scholars are of course the natural audience for Tibayan’s reference-laden work, but in Index, Tibayan is (in large part as a result of the work he chose to index) engaging more broadly with the history of modernism and the modernist canon; exploring what a systematic, serial documentation of a seminal work of photographic criticism can reveal both to the photographically inclined, as well as to those generally familiar with the great titans of modernist thought and art.

By presenting the index as a piece of art, framed and hung like a photograph, Tibayan somehow manages both to confirm and question the great creators and minds of the 20th century; Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Barthes, De Kooning, and the validity of their position on the gallery wall. He also invites, as he states in his artist statement, a critique of canon-building and “the nature of structured knowledge.”

I’ve spent some time in recent months attempting to develop a working knowledge of the canon’s of those educated outside of the West and the limits of our knowledge, something which becomes quickly apparent after perusing Tibayan’s Index, and its documentation of the predominantly white male canon which informed the writing and thinking of Susan Sontag, one of the 20th century’s most important cultural critics, becomes quickly apparent.

I was reminded of the work of Andrea Geyer, another contemporary artist interested in the potential of photography to re-conceptualize our relationship with recorded history, using images to unite thinkers and artists across geographical and time-based boundaries. Imagine to be here, right now (comrades of time) and Insistence, two pieces the artist recently showed in Houston at the Blaffer Art Museum, challenge the primacy of the image and of history by creating new histories, both the real but undocumented, as well as the imaginary.

Tibayan, by indexing the cultural context of Susan Sontag, allows us to consider a wealth of historical figures from Ansel Adams to Bertolt Brecht to Elvis Presley side by side, inviting an occasionally confusing, often inspiring opportunity to consider a diverse array of “historically important” figures and thinkers side by side, while prompting viewers to reconsider what “historically important” means in the increasingly globalized, and as a result, increasingly diversified intellectual world of the 21st century. Who have we left out? And what are the consequences?

JENNIFER SMART