Houston Ballet will return to the Wortham Theater Center this September for their 2021-2022 season. If you’re compelled at this moment to warn the universe, “No take backs,” you aren’t alone. Making plans while just beginning to shake off the dust of a pandemic still feels dubious. However, since when has dust, disaster or deluge deterred Houston Ballet from continuing to plan, make and do?

“It’s unique to Houston Ballet, I think,” says the company’s artistic director Stanton Welch of the organization’s ability to pivot quickly. “We are very much a choreographic, creative company, so the second we realized that this period was not going to be a rest, but a continuation of creation for dance in a non-live performance format, everyone switched focus.”

Foreshadowing their eagerly-awaited reemergence, the company performed recently for hundreds of performance enthusiasts at Miller Outdoor Theatre on May 7 and 8. A mix of live and video performance, Houston Ballet Reignited was the first live performance for the company in more than a year.

The last was their final performance of Ben Stevenson’s The Sleeping Beauty on March 8, 2020. The company was poised to open its next event Forged in Houston, during which they’d unveil a new premiere by Trey McIntyre, when the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic and the United States entered a state of emergency.

At that moment, it might have been difficult to imagine that the outbreak would halt not only the remainder of Houston Ballet’s 50th anniversary season but precipitate the cancelation of their entire 2020-2021 program as well.

“Normally in our cycle of planning we are discussing one-act ballets and full-length ballets with people three to five years in advance.” Welch explains.

“We have a very strong relationship with Houston Methodist and met almost monthly with a panel of doctors, including the head of infectious disease, who is a ballet fan,” Welch adds. “So, when we talked about group work or stretching, we didn’t have to explain and they made a very strict protocol for us to follow.”

As vaccines began to roll out and infection numbers improved, Houston Ballet knew they wanted to have a season and thought they could do it successfully by pushing its start to the latter part of 2021. Including works the company had already planned, invested in or prepared felt important to Welch so that the company and its audience could slip into comfortable familiarity after being apart for so long.

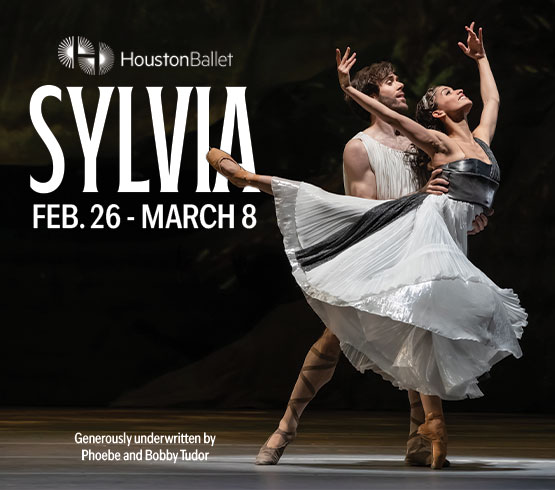

The upcoming season’s full-length ballets, Welch’s own productions of Madame Butterfly, Sylvia and The Nutcracker, as well as George Balanchine’s Jewels, are ballets that are ingrained in the dancers’ bodies either because they are original cast members or because they’ve been performing the roles for years. Reprising a role that is special to her, principal Yuriko Kajiya will appear as Cio Cio San in Butterly, and the cast of Sylvia, which premiered just two years ago in 2019, returns to their roles as well.

The 2021-2022 lineup will also include the premiere (finally!) of Pretty Things by Trey McIntyre, placed again amidst two other works forged in Houston: Jorma Elo’s ONE/end/ONE and Hush by Christopher Bruce. A new ballet by principal dancer Melody Mennite, which was interrupted when it was already quite far along in the creation process, as well as new choreography by fellow principal Connor Walsh, will also debut.

“When you’re a choreographer and you have all the excitement, and there’s momentum that’s suddenly just gone for a year, it’s tough,” says Welch, who was committed to bringing these works to the stage.

Opening the season with the annual Margaret Alkek Williams Jubilee of Dance serves as a celebration, both of the company’s return to the Wortham and Mennite’s 20th anniversary with the company. The mixed program is also a calculated choice to retain some flexibility in the event that circumstances change in the fall.

1 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principal Jessica Collado. Photo by Claire McAdams (2021), Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

2 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principal Jessica Collado. Photo by Claire McAdams (2021), Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

3 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principal Jessica Collado. Photo by Claire McAdams (2021), Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

4 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principals Karina González and Connor Walsh in Stanton Welch’s Sylvia.

Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2019), Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

5 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principal Karina González in Stanton Welch’s Sylvia.

Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2019), Courtesy of Houston Ballet

6 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principals Yuriko Kajiya and Connor Walsh in Stanton Welch’s Madame Butterfly.

Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2016), Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

7 ⁄7

Houston Ballet artists in Rubies, from Jewels, Choreography by George Balanchine, © The George Balanchine Trust.

Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2010), Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

“Every single time you make a plan, it shifts, and the harder you try to hang on to that first plan, you chafe your hands. It’s better to surf it as the problems arise.”

The dancers in a ballet, Welch notes, are only one part of a production that includes orchestra members, stage crew, dressers, ushers and others. Any piece of the puzzle could instigate a wave but Welch stays focused on and encouraged by the positives.

The pleasant job of selecting dancers to travel this summer to Jacob’s Pillow, a National Historical Landmark in Massachusetts that is home to America’s longest-running international dance festival is uplifting. With consideration of American ballet across the continent, The Pillow invited Pacific Northwest Ballet, Boston Ballet and Houston Ballet to send three dancers each to perform work from their own companies, as well as to learn a new ballet to be danced collectively by the nine.

“I like to think if things stay on track, by the time we all come back from summer we’ll be so much further along. Returning to normal classes by August is not what I imagined. To me, that’s much further ahead than I thought we’d be,” says Welch.

As for what the upcoming season will look like for the audience, he expects that things like masks and social distancing are likely still to be part of the experience. Welch also anticipates discussions with costume designers about mask considerations for the children, who may not be eligible for vaccination by the time they’ll be performing on stage during The Nutcracker.

For any regular theatre-goer, the thought is an exhilarating one. For Welch and others, who know deep in their bones that dancers are historically the storytellers of their communities, and have felt an ache for gathering before the fourth wall like pain from a lost appendage, the reconnection of artist and audience cannot come soon enough.

“Our art form is a shared experience,” says Welch. “Seeing the audience’s faces, people you recognize, hearing children giggle, all the gasps and claps — it gives me goosebumps thinking about it.”

Welch even hints at high hopes for the years to come.

“If you think about after the last [1918] plague, it was the Roaring Twenties, an amazing time for architecture, art and food. So, hopefully in a year or two, we can put this in the past and there will be a new renaissance of coming together.”

—NICHELLE SUZANNE