In 1966, Gordon Parks, one of the most acclaimed photographers of the 20th century, set out to profile rising civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael for Life magazine. After four months of following Carmichael and capturing him as speaker, organizer and leader but also as a young family man carrying enormous responsibilities and burdens, Parks’s Life feature revealed through photos and words a truer vision of Carmichael than the news headlines portrayed.

“These two major figures, Stokely Carmichael and Gordon Parks, with their different backgrounds, different generations were different as could be, but they meet at this pivotal moment within the Civil Rights movement and then go off on their separate ways again,” observes exhibition curator Lisa Volpe. “For me it’s that moment that’s so interesting: how Stokely got there; how Parks got there; how Parks viewed Stokely at that moment and what happened next.”

When artist and subject first met, Parks was already known as a pioneering photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and Office of War Information (OWI) in the 40s. The first full-time Black photographer for Life, Parks was also a writer and composer of music. Only a few years after his profile of Carmichael, Parks would become the first Black director to helm a major Hollywood film with The Learning Tree and the genre-defining Shaft.

While the Life profile featured five photos, and Parks’s powerful essay profile of Carmichael, the artist had taken over 700 photos as he traveled with Carmichael on and off from the fall of 1966 to the spring of 1967.

Along with those five published photos and the now elusive Life essay, Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power will feature 50 photographs and contact sheets never before published or exhibited, as well as footage of Carmichael’s speeches and interviews.

Volpe organized the exhibition after an invitation from the Gordon Parks Foundation to look through their vast collection of Parks’ work for a possible show. Volpe quickly focused on this moment in civil rights history when artist and subject intersected.

“It just felt very of-the-now. I was consistently shocked when reading Carmichael’s definition of Black Power or when I was reading of the movement from 1966 to ’67,” says Volpe. “It felt like reading a newspaper today. So much has not changed. Our vocabulary, our language has changed, but the core ideas have not.”

1 ⁄8

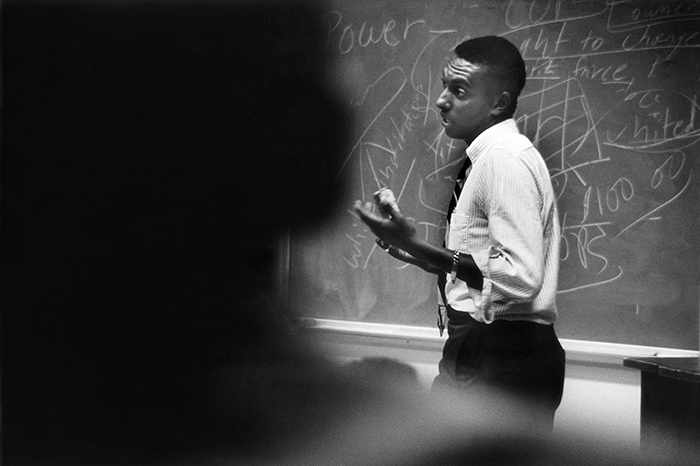

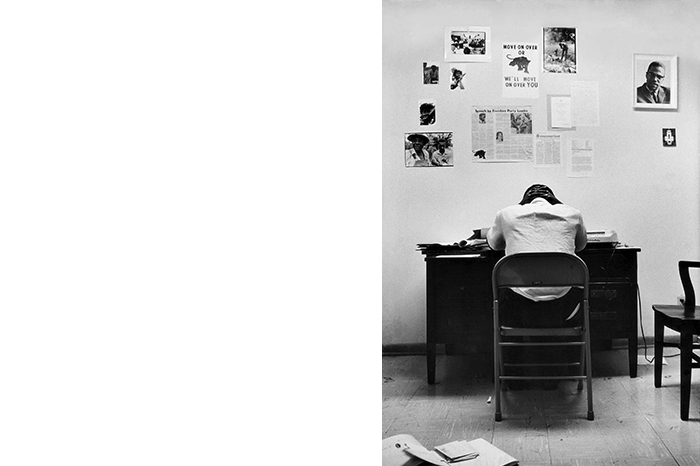

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Los Angeles, California, 1967, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

2 ⁄8

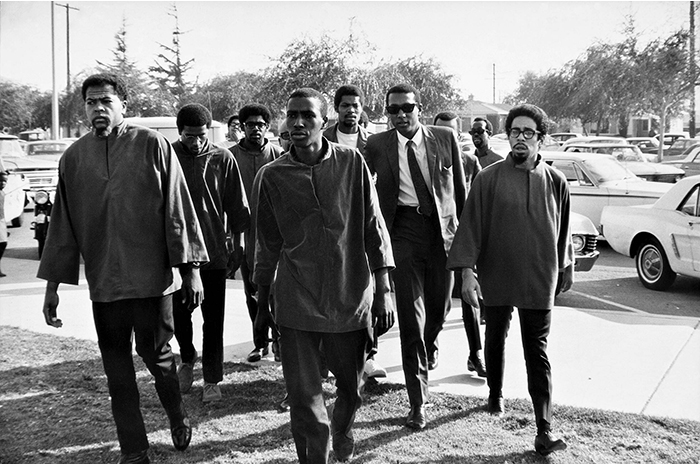

Gordon Parks, Untitled, 1967, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

3 ⁄8

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Watts, California, 1967, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

4 ⁄8

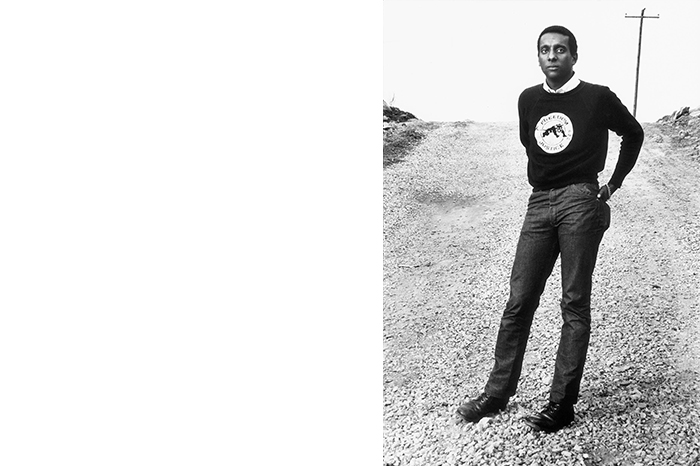

Gordon Parks, Stokely Carmichael, Lowndes County, Alabama, 1966, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Carmichael on the road in Lowndes County, Alabama, 1966.

5 ⁄8

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Atlanta, Georgia, 1966, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Carmichael at his desk at SNCC’s Atlanta headquarters, 1966.

6 ⁄8

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Los Angeles, California, 1966, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Carmichael addresses the Watts crowd from a truck bed, Los Angeles 1966.

7 ⁄8

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Bronx, New York, 1967, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Mary Charles Carmichael serving her children Lynette and Stokely at Lynette’s wedding dinner in the Bronx, 1966.

8 ⁄8

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Watts, California, 1967, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Members of the US Organization, including James Doss-Tayari (left), Tommy Jaquette-Mfikiri (behind Carmichael), and Ken Seaton-Msemaji (right), walking with Carmichael to the Watts rally, Los Angeles, 1966.

“There’s something about how close he gets to people that you really feel like you’re there. There’s no distance between the subject and you. He really became a fly on the wall trying to capture this in the most honest way possible,” Volpe explains, but also notes, “This is how he writes, too. All his essays for Life he writes in first person. He is letting you experience exactly what he experienced and exactly how he experienced it.”

When selecting photos for the exhibition, Volpe put on her curating detective hat to decipher why Parks took so many shots of certain activities. She also spoke to everyone in the photos she could find to “understand the moment, the tenor and the emotion of the time.”

“I’m trying to recreate his thoughts, as much as that is possible in any way. So many of the photos are about Stokely being young and having this huge responsibility on his shoulders for such a young man.”

“It’s this amazing mix that now I can recognize of him being responsible, taking responsibility for people’s lives but also finding some joy in it,” explains Volpe, adding that this was the kind of story Parks tells with the photographs, even if the white Life editors didn’t recognize that story.

Volpe believes the exhibition will show the many different facets of Carmichael that Parks captured but the Life editors did not necessarily present.

“What they don’t include are his moments of joy. There are so many moments in here of him just laughing or having a good time and finding joy,” says Volpe. “Parks writes one line about it in Life, but the photo editors didn’t pick up on that. But because Parks gives it to us in the images, it seemed like it was something really important to include in the exhibition.”

Yet, by focusing on Parks’ exploration of one subject—four months in the life of Carmichael—the exhibit also gives us new behind-the-lens insights into the mind and process of one of America’s most visionary photographers.

—TARRA GAINES