It is a crisp, chilly night in January. I am standing in front of the Meyerson Symphony Center, I.M. Pei’s modernist masterpiece of soaring limestone and curving glass, to admire for a moment its precise geometry and sculptural grandeur, before stepping into the warm, welcoming interior for an evening with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra.

It’s the start of my whirlwind tour of the Dallas Arts District, now celebrating 40 years. (Congrats to Lily Cabatu Weiss and her team.) Improbably, in all the years I have lived in Houston (23) and all the time I have been an arts writer in Texas (5), I had never been to Dallas. I am here now as a first time arts tourist, eager to absorb the wonders of a new place, open to every experience that might come my way.

Back in the Meyerson, I walk the entire span of the building on each level, admiring a new perspective from every angle. Other than Ellsworth Kelly’s striking Dallas Panels (Blue, Green, Black, Red) (1989) which boldly scale the full height of the atrium wall, the pure forms of the architecture need no adornment.

I am here for the music. The Meyerson has been the beloved home of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra since its opening in 1989. I have long heard about the golden acoustics of the hall, designed by Russell Johnson with meticulous, scientific precision. The first thing I notice is the enormous acoustical canopy suspended from the ceiling, bearing an uncanny likeness to the Starship Enterprise, and just as complex in its functions. The space feels both intimate and energetic. On this night the orchestra unleashed the elemental power of Finnish composer Jean Sibelius’s Symphony No. 2. The quietest pizzicati resonated, tender melodic lines were warm and round, the scherzo sparkled, the brass swelled with clarity and presence, and the finale soared to a glorious climax. How exhilarating it is to hear great orchestral music in this inimitable hall.

I’m staying at Hall Arts Hotel, which opened in the heart of the arts district at the end of 2019, right before the global pandemic. Its sleek, contemporary design fits in neatly with two of the newest venues (2009) in the district – Rem Koolhaas’s ultra-cool Wyly Theatre across the hotel entrance and Norman Foster’s gleaming Winspear Opera House nearby. Hall Arts is the brainchild of Craig and Kathryn Hall, Dallas’s leading entrepreneurial power couple, who also happen to be avid art collectors. They wanted to create a hub for people to gather while visiting the surrounding arts venues, and showcase their personal art collection in a spacious, luxurious setting.

Lava Thomas’s Resistance Reverb: Movement 1 (2018), a dazzling symphony of pink tambourines dangling from the lobby ceiling, references the historical use of tambourines by protestors and activists during marches and demonstrations, particularly highlighting voices from women’s movements, with fragments of historical speeches inscribed on the instruments.

Scottish painter Alison Watt transfigures a simple knot in the fabric into a monumental painting in four panels. Volvere (2019) alludes to the mysteries of the feminine and the power of intimacy. By the elevator, Beirut-based artist Najla el Zein has turned spoons into a sculptural wall lamp in 6302 Spoons (2012), transforming a utilitarian, everyday object into a strange, reptile-like material that reflects light and movement.

Nekisha Durrett’s whimsical, pop art inflected Couple No. 1 (2019) addresses ideas of gender and sexuality, while her text-based installation Then I Wish That I Could Come Back as a Flower (2018), conjures layers of meaning. Composed in part of cotton balls, Spanish moss, lotus pods, cedar cones, eucalyptus, and burlap, the piece ponders existential questions as it evokes the sufferings of enslaved people who worked in the cotton fields as well as the aesthetics of the South.

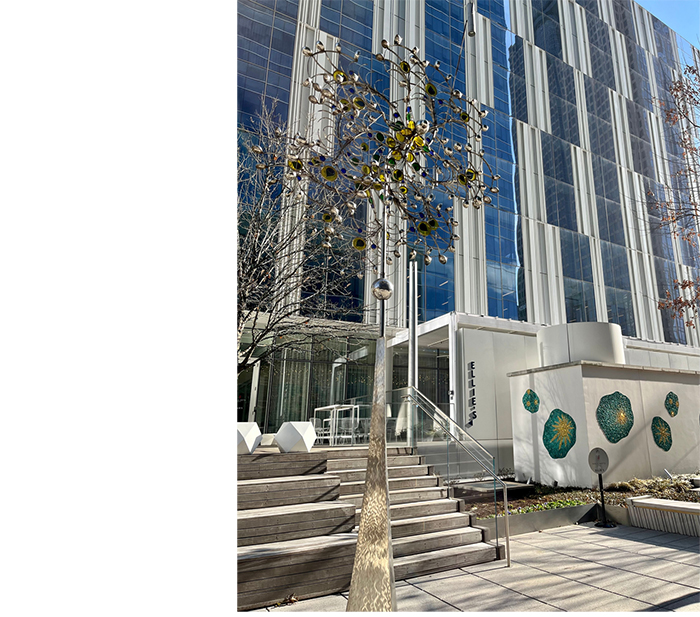

At Ellie’s, the restaurant located within Hall Arts, Spencer Finch’s light installation Asteroid (2019) forms a starry canopy above while Kristin Baker’s expansive and layered landscape Spangled Ramparts (2019) unfolds along the wall from sea to shining sea. Art flows naturally from the interior to the exterior. From the terrace, where a dreamlike mosaic of swirling blue and white danced before my eyes, I could step down to the Texas Sculpture Walk and have a fun stroll among a dozen contemporary sculptures by James Surls, Jesús Moroles, Jim LaPaso, Joseph Havel, Deborah Ballard, and others.

1 ⁄10

Sherry Cheng overlooking the lobby at Hall Arts Hotel. In view are Linda Šormová Melichová 's Bird's Nest and Lava Thomas's Resistance Reverb: Movement 1. Photo by Dmitry Bazykin.

2 ⁄10

Jim LaPaso’s Nefertiti Rising, with views of Hall Arts Hotel and Ellie’s. On the wall is Sonia King’s mosaic installation VisionShift. Photo by Sherry Cheng.

3 ⁄10

Sherry Cheng standing beside Deborah Ballard's Reflection Series XI, Texas Sculpture Walk in the Dallas Arts District. Photo by Dmitry Bazykin.

4 ⁄10

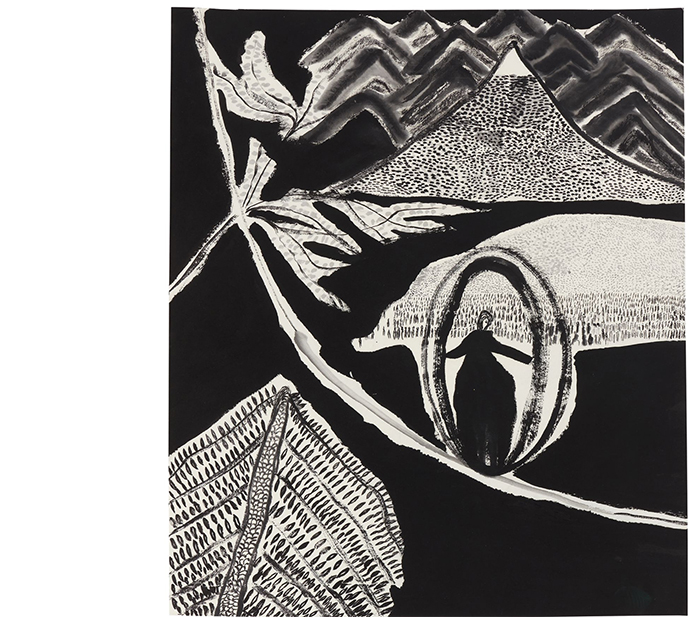

Matthew Wong, The Performance, 2017. Ink on rice paper. Matthew Wong Foundation. Image credit: © 2022 Matthew Wong Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

5 ⁄10

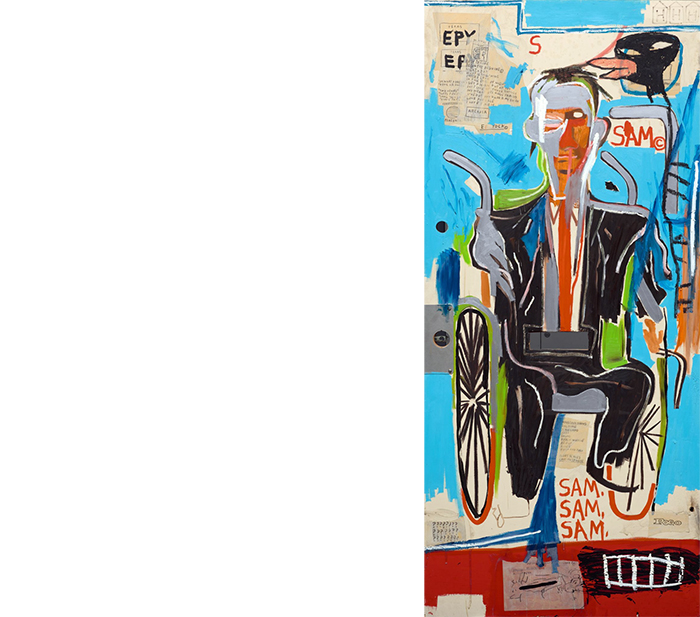

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sam F, 1985, oil on door, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Samuel N. and Helga A. Feldman, 2019.31, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

6 ⁄10

Octavio Medellín, Genoveva of Brabante, 1949, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr.

7 ⁄10

Hamid Rahmanian’s Song of the North, presented by TITAS. Photo courtesy of the Artist.

8 ⁄10

Willem de Kooning's Seated Woman in Nasher Garden. Photo by Tim Hursley.

9 ⁄10

Meyerson Symphony Hall. Photo courtesy of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra.

10 ⁄10

Sherry Cheng in front of the Nancy Best Fountain, Klyde Warren Park. Photo by Dmitry Bazykin.

The DMA, established in 1903, was the first arts institution to relocate to the Dallas Arts District back in 1984. The building, designed by renowned architect Edward Larrabee Barnes, takes advantage of the natural incline of the street. The deceptively low, quiet structure opens up inside to reveal a wide hallway leading to architectural surprises like a high barrel-vaulted room that branches into four quadrant galleries.

Right now this central space is activated by the temporary exhibition Movement: A Legacy of Kineticism (Sept. 18, 2022-July 16, 2023), featuring 80 works drawn from the museum’s own collection of Kinetic art. I especially appreciated the section tracing the historical context of Kineticism, which included a view of Suprematism and Constructivism in Russia circa 1910s-1920s. A lithograph under a glass case caught my eye, an energetic and graceful abstract illustration called Gardeners over the Vines (1913) by Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova. She founded the Rayonist movement which emphasized rays of light and its reflections. The most captivating piece in the exhibit for me was Olafur Eliasson’s The outside of in (2008), a 12-minutes-long light projection that plays with colors and shapes as they assemble, morph, or deconstruct, confounding the viewer’s mind with overlapping forms and illusory afterimages.

I was thrilled to catch Matthew Wong’s posthumous solo exhibition The Realm of Appearances (through Feb. 19, 2023). It’s a stunningly beautiful and poignant tribute to this singular artist’s creative vision. Assimilating a wide range of influences from Chinese ink painting to Van Gogh, the self-taught Wong died by suicide at the age of 35 in 2019. What moved me deeply is the way his paintings communicate emotion, whether through a feverishly dotted night sky or footprints in a snowy forest, a solitary flower or an enchanted kingdom, a Rothko-esque horizon or a lone figure in a strange landscape.

Upstairs in the Tower gallery, it was the last weekend of Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form, a long overdue retrospective for the Mexican-born sculptor whose six decade career in Texas leaves a rich artistic legacy. It’s a deep and well-curated exhibition, featuring 80 works in a variety of materials including wood, terra cotta, stone, metal, and ceramics, as well as examining the artist’s numerous public commissions. If I had to pick one favorite, it would have to be Genoveva of Brabante (1948-49), a direct carving from a 500-pound log of Honduras red mahogany. Inspired by the medieval legend of a woman wrongfully accused of adultery, banished, then saved by a deer, the graceful female figure with gentle curves holds a small deer closely against her body, a lyrical expression of gratitude.

Stepping into the sunshine, I was ready for some nourishment, preferably al fresco. Luckily, Klyde Warren Park, which just celebrated its 10th anniversary, is nearby and provides plenty of options for food as well as gentle respite from art overdose. The newest addition to the park is the artsy and splashy Nancy Best Fountain, composed of three stainless steel sculptural “trees” surrounded by a chorus of dancing water.

The Nasher Sculpture Center galleries were closed for installations during my visit, which was just as well because all I wanted to do was relax with a stroll through its beautifully landscaped sculpture garden. Renzo Piano envisioned the Nasher as a “museum without a roof.” The vaulted glass ceiling floats above the travertine stone walls, continuing into the exterior seamlessly. The garden extends the lines of the architecture, giving the whole a sense of perfect proportion and harmony.

My favorite sculptures are ones with which I can interact. I imagine myself as one of the group of headless figures in Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Bronze Crowd (1991). I walk between the bending steel plates of Richard Serra’s imposing My Curves Are Not Mad (1987), literally the heaviest sculpture in the Nasher collection at over 100,000 pounds. Nicole Eisenman created an ensemble of larger-than-life bronze figures for Fountain (2017). These make me smile, especially the one holding a beer and another possibly sleeping off a hangover on the grass.

A completely unique and epic experience awaited me at the Moody Performance Hall (completed in 2012), the newest venue in the Dallas Arts District. Built as a multi-disciplinary performance space, the hall is perfectly suited for the diverse offerings of mid-sized arts organizations like TITAS/DANCE UNBOUND.

I am here to see Iranian director Hamid Rahmanian’s cinematic shadow puppet theater Song of the North (presented by TITAS), based on the love story of Bijan and Manijeh from the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, versified by the Persian poet Ferdowsi in the tenth century. It’s the second installment of a trilogy that began with Feathers of Fire (premiered in 2016). 483 handmade puppets come alive against projected animation of exquisite imagery, accompanied by dramatic music, and realized through precise, skilled movement. I was completely immersed in the theatrical experience which transported me to the beguiling world of ancient Persia. I was equally stunned by the sheer talent, hard work, skill, and imagination it must have taken to create a work of such magnificence.

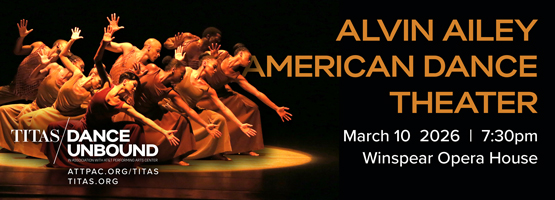

The remainder of the TITAS season features a wide range of dance offerings from Trinity Irish Dance Company, Alan Lake Factori(e), Greg Maqoma’s Vuyani Dance Theatre, and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. When Charles Santos, the long time Executive Director of TITAS, took to the stage to introduce Rahmanian, he gave a great reason for why a dance presenter is bringing this show, which defies genre and category, to Dallas. “A lot of people asked why we are doing this particular show that’s centered around puppetry, and the answer is because we can,” he said to the clamorous applause of a full house. “It’s just too special not to bring.”

I have barely scratched the surface in my 42 hours in the Dallas Arts District. There is so much more to experience. I imagine a return trip to see presentations by the Dallas Theater Center, Dallas Black Dance Theatre, and all the diverse happenings on the campus of the AT&T Performing Arts Center. Now if they can just build that Houston to Dallas high-speed train, I would hop on it this weekend to catch Dallas Opera’s Das Rheingold at the Winspear.

—SHERRY CHENG