If there’s one thing Louis XIV was known for, it was opulence. The Sun King transformed Versailles into a gilded palace, adorning it inside and out in gold leaf and filling the rooms with silver furnishings. So when he and other 17th and 18th century European Catholic monarchs decided to send offerings to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, it’s no surprise that these treasures were masterfully crafted from gold and silver, woven with rare silks and damask, and encrusted with precious gems.

Kimbell deputy director George Shackelford arranged its Fort Worth finale, and he says the rarity of these objects cannot be overstated.

“Many of these items survived only because they were in Jerusalem,” he says. “For example, a lot of French silver from that time was melted down—Versailles used to have these eight-foot-tall candelabras that ran the length of the Hall of Mirrors, but they were all repurposed into coins. So many contemporary items were damaged or lost entirely.”

1 ⁄5

Monstrance, Naples, 1746, gold, rubies, emeralds and diamonds. Terra Sancta Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

2 ⁄5

Antonio de Laurentiis, Throne of Eucharistic Exposition, Naples, 1754, gold, gilt copper, almandine garnets, amethysts, rock crystal, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, carnelians, peridots, smoky quartzes, glass, and doublets. Terra Sancta Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

3 ⁄5

Crozier (detail), Naples, 1756, gold, rubies, diamonds, emeralds, almandine garnets, quartzes, and glass. Terra Sancta Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

4 ⁄5

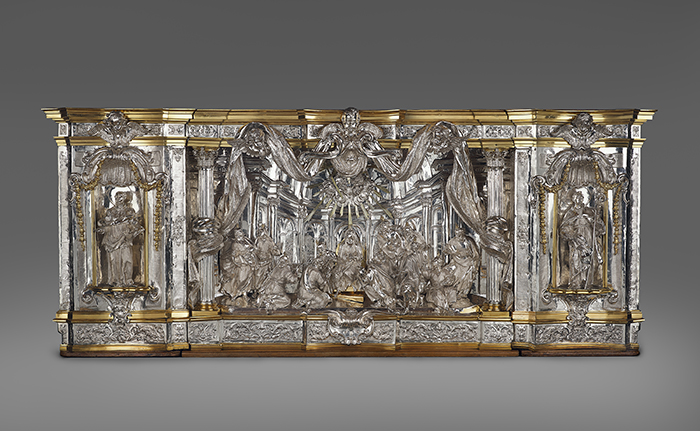

Gennaro De Blasio, Altar Frontal or Antependium, Naples, 1731, cast, chased, and repoussé silver with gilded details. Terra Sancta Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

5 ⁄5

Probably workshop of Domenico Piola, Cope of the Red Pontifical Set of Vestments of Genoa, Genoa, 1686–97, satin ground, silk thread, and painting on silk. Terra Sancta Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

The liturgical objects, conversely, were safeguarded for centuries and used by the Franciscan friars who maintain the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, built on the presumed site of Jesus of Nazareth’s death, burial, and resurrection. The collection includes dazzling reliquaries, crosses, candlesticks, chalices, and vestments representing the pinnacle of European goldsmithing and textile design, ordered by rulers such as King Philip IV of Spain, the Holy Roman Emperors, and the Doges of Venice and Genoa.

“All these powerful commissioners from Paris, Lisbon, Messina, and more were sending these exquisitely crafted items as an act of faith to the other end of the Mediterranean, a place they would probably never go to,” says Shackelford. “The act of donation was their pilgrimage.”

Though Shackelford points out that the Kimbell is secular, he stresses that it’s important to recognize the power of faith that infused the making of these treasures, the provenance of which spans the 1580s to the 1760s.

“We have to back up and put ourselves in the mindset of the people of the time,” he says. “This was like building a cathedral or a church, except you were sending it off to this holy site. The dazzling quality of it can seem almost kind of kitschy to our modernist taste, but to them it was a prayer in gold.”

Coming on the heels of Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection, another extremely rare exhibition, The Holy Sepulcher might feel like whiplash. Instead of cool, creamy marble, visitors will be surrounded by dazzling gold, shimmering silver, richly embroidered fabrics, a riot of colorful enamel, and sparkling rubies, emeralds, sapphires, and diamonds.

Torchères—tall, ornamental stands for candlesticks built of approximately 60 pieces each—are also featured in the exhibition. They hail from Venice in 1765, though the metal is much older. In 1757, Greek Orthodox clergy ransacked the Holy Sepulcher, damaging a number of silver liturgical objects. Some of that silver was reclaimed and melted down to create new objects before returning to Jerusalem in its transformed state.

A full tableau of liturgical items, sacred vestments, and other textiles used in a Mass makes it easy to see how these artifacts were more than decorative.

And Shackelford insists that to be fully understood, that magnificence needs to be experienced in person.

“This is the height of European craftsmanship through just shy of 200 years, and it’s a wonderful thing to compare and contrast over time the changes in style, the royal individuals and their different tastes, and the influence of art,” he says. “The photographs do give a sense of how wonderful these items are, but you need to be in front of them to see how the light catches the jewels, the brilliance of the silver, the glint of the gold. These objects have no equivalent anywhere else in the world.”

—LINDSEY WILSON