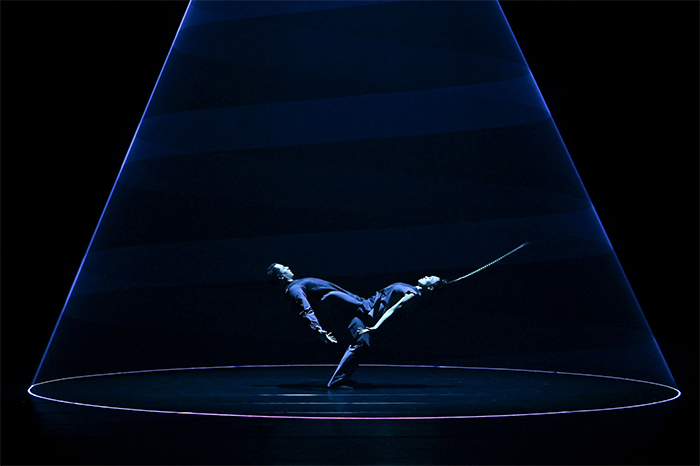

Choreographers, like artists of all mediums, find inspiration in both grand realizations and quiet moments. For the young Taiwanese choreographer Lai Hung-Chung, his hallmark work Birdy came from a little seen 1984 Alan Parker film of the same name, and his own stirring desire to take flight. Texas audiences will be able to see this dynamo of a work in Houston courtesy of Performing Arts Houston on Nov. 21 and 22, and then on Dec.13 in Dallas as part of the TITAS/DANCE UNBOUND series.

The imagery of the dance, as well as its precise movements and billowing arm sequences, suggests the world of birds. The work’s signature costume prop is a pheasant feather, but the dance is rooted in human traditions and physical practices. For example, tai-chi plays an integral part of the aesthetics of the work, especially its use of spiraling and the discharge of energy.

“Imagine you have a spine,” says Hung-Chung. “This spine is expressed through the feather prop in the work. Imagine you are throwing a ball. When you throw it, the force continues outward, but where does the power go?” The combination of tai-chi and the pheasant feather prop allow Hung-Chung to demonstrate the results of this scenario, which creates a spiraling effect onstage that’s quite gorgeous.

1 ⁄6

Hung Dance in Birdy. Photo by LIU Ren-haur.

2 ⁄6

Hung Dance in Birdy. Photo by LIU Ren-haur.

3 ⁄6

Hung Dance in Birdy. Photo by LIU Ren-haur.

4 ⁄6

Hung Dance in Birdy. Photo by LIU Ren-haur.

5 ⁄6

Hung Dance in Birdy. Photo by LIU Ren-haur.

6 ⁄6

Hung Dance in Birdy. Photo by LIU Ren-haur.

For Hung-Chung, this spiral has larger metaphorical implications. “Everything affects the next point of action, and the next event. It’s a continuum, like history and literature. They go on and on.”

Birdy has been performed more than 250 times throughout the world, and wherever it travels, it’s greeted with much acclaim from critics and enthusiasm from audiences, including its US premiere in June of last year at the American Dance Festival. For Hung-Chung, the dance is not thematic, but conceptual, and it’s the central concept and the aesthetics that it produces that makes the work so popular. “Without the training of tai chi and Taiwanese traditional dance, it would be hard to express,” he says. “Audiences enjoy the unique choreography and the top technique—you might see some quite dangerous movements.”

The style of Hung Dance is lush and dramatic, but different from other contemporary dance companies from the region. Audiences might be more familiar with Taiwan’s Cloud Gather Dance Theatre, but Hung Dance has developed a new system that is quite different. Hung-Chung explains that his company’s training is in tai chi and contemporary dance, but “the audience can expect it to be more subtle and not as explicit.”

The title character of Alan Parker’s 1984 film yearns to fly like his beloved birds, but like the dancers of Hung-Chung’s work, finds himself grounded by the physical constraints of the human world. At one point in the dance, rattan poles form a cage. Another prop taken from Chinese opera, the rawness of the rattan poles symbolizes, for Hung-Chung, our original form or a return to self. He adds, “Aside from the props, the lighting and the movement create a symmetry that will break through inside people’s hearts and minds.”

—ADAM CASTAÑEDA