Time is a precious commodity, and as we move further away from the standstill of the pandemic years, many of us are finding that we have far less than we would like. This reality is one of several entry points Houston dance leader Karen Stokes is taking to mine the concept of liminality in her latest work, 4 Corners, which runs Jan. 30-Feb. 8, 2026 at the Midtown Arts and Theater Center Houston.

Stokes is a research-based dancemaker. Her last work, Mapping and Glaciers, an examination of literal and figurative landscapes, was a multi-year endeavor. 4 Corners is proving to be more a reflection of a specific period of Stokes’ life, and even though there is not a central research topic, her signature process hasn’t shifted all that much. The piece started with six rehearsal sessions with three dancers in fall 2023, and has expanded to four dancers through the three-year development arc. “The piece itself is attempting something that feels different to me,” she says, before also noting that this is the smallest cast of dancers she has used in her company format.

The challenge of this work has been attempting to describe conceptual material that doesn’t have a tangible form. “I chose to work on something that deals with the in-between spaces of life,” she says. “We always focus on the idea that transition is something between two places, but is there something primary about transition? What is that groundless, uncertain liminal space?”

1 ⁄4

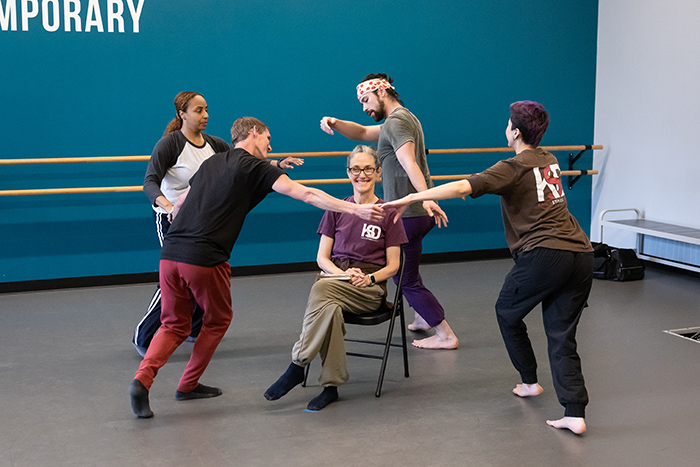

Karen Stokes Dance rehearsing 4 Corners. Photo by Lynn Lane and courtesy of Karen Stokes Dance.

2 ⁄4

Karen Stokes Dance rehearsing 4 Corners. Photo by Lynn Lane and courtesy of Karen Stokes Dance.

3 ⁄4

Karen Stokes Dance rehearsing 4 Corners. Photo by Lynn Lane and courtesy of Karen Stokes Dance.

4 ⁄4

Karen Stokes Dance rehearsing 4 Corners. Photo by Lynn Lane and courtesy of Karen Stokes Dance.

Stokes has always had an interest in time and space in her work, but this time she made the decision to create a four-sided work early on in the process. The way dance is currently being disseminated in the culture was one of the primary motivations for the decision. “One of the things that’s aggravating me is how much we are looking at flat dance now,” she says. “On YouTube, Tik Tok, and that’s not something I’m interested in.”

Stokes prefers to think of dancers as three-dimensional sculptures moving through space, heightened with moments of interaction and dissipation. To keep the focal point on these living sculptures, there won’t be projections on their bodies as in Mapping and Glaciers, another example of how this work is a much more stripped-down iteration of Stokes’ choreography.

The better part of a year was spent creating movement in a completely new way. “I would create some material, often in silence to start,” she says. “And then I would look at it from each side and make changes.” Once she realized that she was in the habit of stationing herself next to the music speaker, she forced herself to move to different vantage points in the room. It was then that she was able to experience her work in new ways.

Her movement is being brought to life by Houston-based talents Brittany Bass, Bryan Peck, Michelle Reyes, and Donald Sayre. Each dancer is a distinct performer, but under Stokes direction, they move like a community. While there are not many improvisational contributions in Stoke’s process, they shape the movement through their individual nuances.

The two have never met, with all of their interactions being through email, phone, and Zoom. The process has been a good one, and she describes it almost like film scorning, as she was able to give Morris a great deal of material once he entered the project. Bringing in Morris later was part of the strategy to keep the rehearsal process as quiet as possible.

“Our world is too crowded,” she says. “I feel overwhelmed by how we’re pushed by the clock, with everything coming at us. I need something that gives me some stretching room.”

—ADAM CASTAÑEDA