When visitors step into New Horizons: The Western Landscape at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, they won’t find sagebrush clichés, cowboys in silhouette, or sweeping vistas painted to satisfy nostalgia. Instead, the Fort Worth museum invites audiences into a far more complicated, contemporary, and kaleidoscopic vision of the American West, one shaped by 14 living artists who approach the region as a place of memory, change, identity, and contradiction.

“This exhibition really comes from asking what the idea of the West means now,” says Andrew Eschelbacher, the museum’s director of collections & exhibitions and co-curator of New Horizons, along with junior curator Arianna Tejada. “We have this incredible historical collection that shapes how the West has been pictured, but it also gives us a jumping-off point to think about how artists are engaging with the landscape today. The West isn’t a monolith. It takes many forms, and we wanted to show just how varied and personal those perspectives are.”

Spanning painting and sculpture, New Horizons features the artists whose experiences stretch from Indigenous communities in the Southwest to the urban corridors of Los Angeles, to the hybrid cultural spaces where rural and metropolitan landscapes meet. The lineup includes Tony Abeyta, Bale Creek Allen, Sarah Ayala, Mick Doellinger, Craig George, Tiffany Huff, Dean Mitchell, Winter Rusiloski, Michael Scott, Kay WalkingStick, Don Stinson, Z.Z. Wei, Camille Woods, and Steven Yazzie.

1 ⁄8

Tiffany Huff (b. 1980), Cosmic Repose, 2025, oil on wood panel, Courtesy of Commerce Gallery, © Tiffany Huff

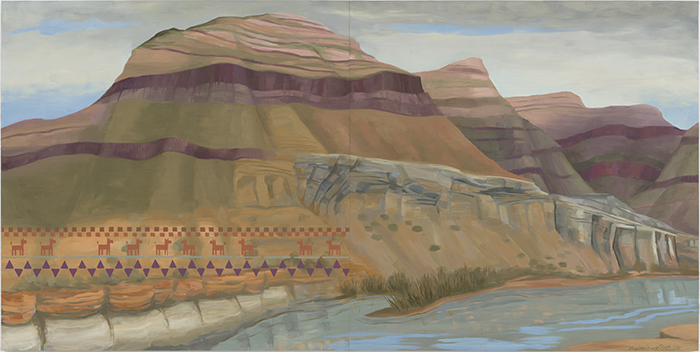

2 ⁄8

Kay WalkingStick (b. 1935), Salt River Canyon, 2016, oil on wood panels, William P Healey, © Kay WalkingStick, Photo by JSP Art Photography

3 ⁄8

Dean Mitchell (b. 1957), Pima-Maricopa Reservation, 2013, oil on panel, Dean Mitchell, © Dean Mitchell

4 ⁄8

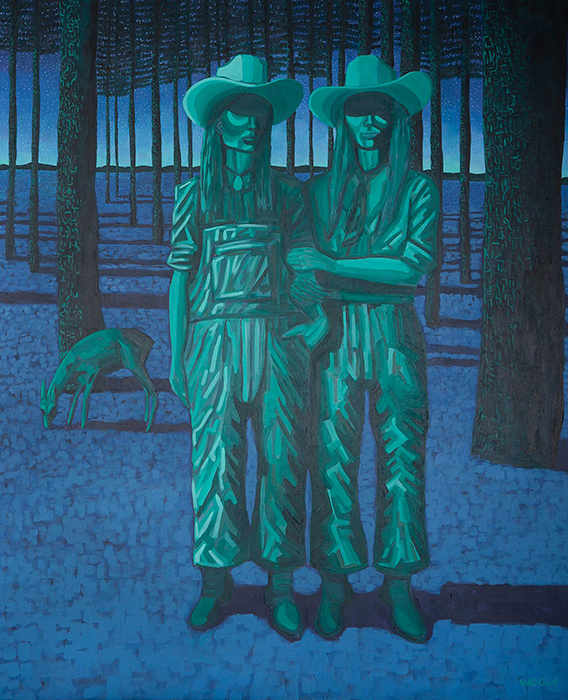

Camille Woods (b. 1984), To Have and To Hold, 2024, acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of Commerce Gallery, © Camille Woods

5 ⁄8

Winter Rusiloski (b. 1979), Anniversary Storm Over Orion's Ridge, 2024, oil on canvas, Artspace 111, © Winter Rusiloski

6 ⁄8

Steven Yazzie (b. 1970), Motifs in Pink, 2024, oil on canvas, Private Collection, © Steven Yazzie

7 ⁄8

Michael Scott (b. 1952), Ghost Owls at Mt. Ranier, 2016-19, oil on linen panel, Courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM, © Michael Scott

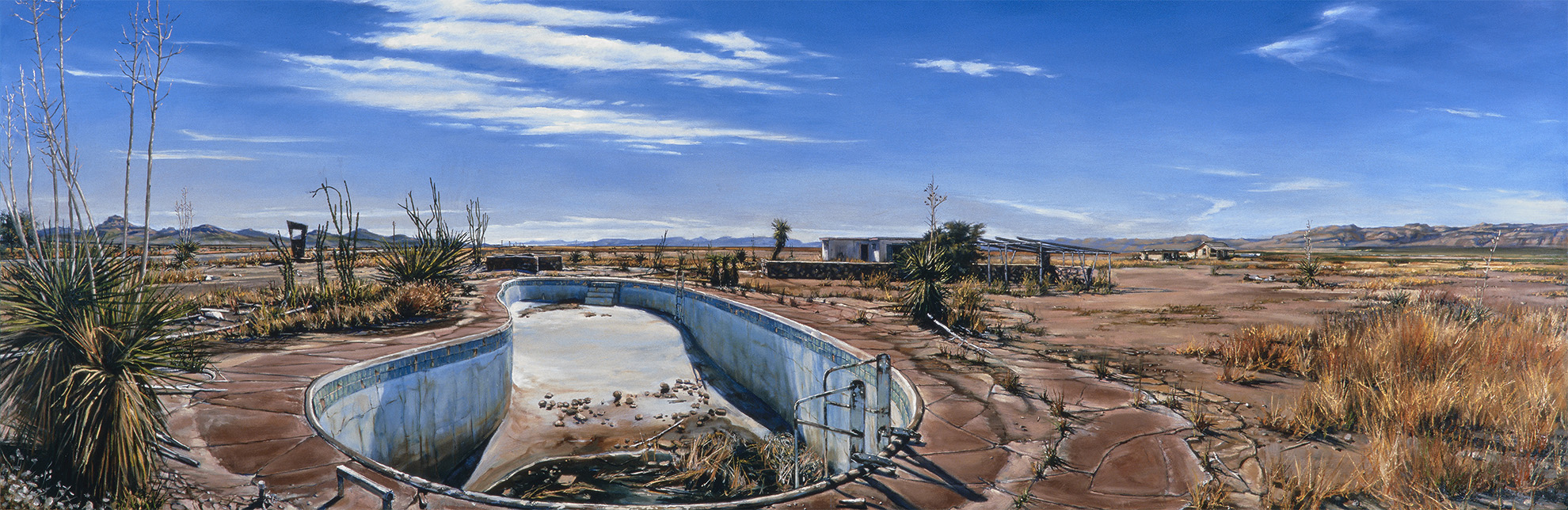

8 ⁄8

Don Stinson (b. 1956), Lone Star and Pool: Lobos, Texas, 2000, oil on wood panel, Don Stinson, Artist, © Don Stinson, Artist

In a departure from traditional museum practice, the curators opted not to write wall labels. Instead, each artist was invited to describe in their own words how the West informs their work. “Who better to tell the story than the artist?” Eschelbacher says. “The temperament of the land—the sky, the light, the unpredictability—is constantly shifting. These artists respond to that firsthand. Their voices are essential.”

One of those voices belongs to Tony Abeyta, the acclaimed Diné artist whose work is represented both in the show and as part of the curatorial team. Abeyta, who grew up in Gallup, New Mexico, is known for mixed media and oil paintings that combine modernist sensibilities with ancestral Navajo iconography and the atmospheric drama of the Southwest.

Abeyta says the invitation to co-curate felt like a natural extension of his own artistic inquiry. “I was honored to be asked,” he says. “This exhibition is right up my alley—the story of landscape, the sense of place, the emotional ties we have to the land. There’s the romantic perspective, the nostalgic Route 66 ideas. But there are also cultural perspectives, Indigenous perspectives, and contemporary urban perspectives. The West holds all of those.”

As he reviewed the works under consideration, a mood emerged, one he describes as “haunting.”

“There’s this sense of loneliness in the land,” Abeyta reflects. “Not in a sad way, but in a way that reminds you the land exists on its own. We’re its guests. We cultivate it, we use it, we connect with it, but it has its own permanence, its own memory.”

That sense of permanence versus ephemerality appears in many works, including Bale Creek Allen’s bronze tumbleweed. “Tumbleweeds are these roaming spirits,” Abeyta says. “But cast in bronze, suddenly there’s something eternal about it.”

Craig George’s paintings, meanwhile, reflect a life split between downtown Los Angeles and summers on his grandmother’s reservation. “He’s living in two realms,” Abeyta says. “Urban landscapes with coffee bars and streetlights, but also traditional elements that connect him to his Native identity. That coexistence is very real for many of us.”

Other works expand the emotional and imaginative terrain of the West: Michael Scott’s nightscape, which Abeyta describes as “tied to the dream realm,” and Don Stinson’s abandoned swimming pool, a symbol of developments that rose and fell with shifting economies and rerouted highways.

“It’s the story of what happens to land,” Abeyta says. “We develop it, then it reclaims itself.”

In the end, New Horizons is less about replacing one narrative of the West with another than about complicating the view.

“We see this as additive, not oppositional,” Eschelbacher explains. “Remington can be the West. Tony can be the West. And you—your lived experience—can be the West too.”

—LINDSEY WILSON