From a self-portrait worth $55 million to hand-painted shoes on Etsy, from egg cups to a biographical ballet and lookalike festivals across the globe, very few artists have ever inspired and driven the world’s imagination like Frida Kahlo.

Such a rare artist deserves an exhibition also unlike anything seen before, so several years ago when called on to organize a new show of Kahlo’s work, Ramírez, who is the MFAH’s Curator of Latin American Art and founding director of its International Center for the Arts of the Americas, knew that after the multitude of retrospectives over the decades, this Frida Phenomenon called for a different perspective. Frida: The Making of an Icon features Kahlo’s art and examines her ability to turn her own life into artistic expression, but it also explores Frida as a cultural, and sometimes even spiritual, icon and her influence on so many generations of activists, thinkers, and fellow artists.

“At the time of her death in 1954, Kahlo was known to intellectual and artistic circles in Mexico and the United States. She had a devout series of collectors who followed her, but she was not a mainstream name,” explains Ramírez.

In the 1960s, students and artists in Mexico began to have a new appreciation of Kahlo and with the publication of important biographies of Kahlo, first in Spanish and later English, waves of appreciation of her art and life began to spread until she became the cultural phenomenon she is today.

1 ⁄8

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait (in a Velvet Dress), 1926, oil on canvas, private collection. © 2025 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, Mexico, D.F./ Artists Rights Society, New York.

2 ⁄8

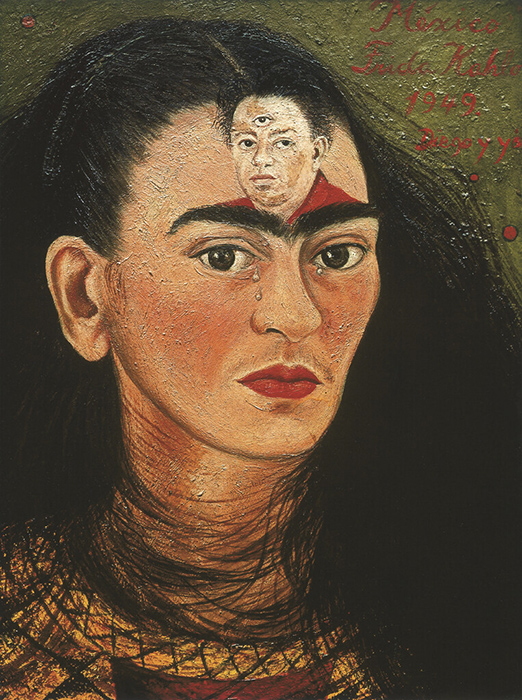

Frida Kahlo, Diego and I, 1949, oil on canvas, Collection of Eduardo F. Costantini. © 2025 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, Mexico, D.F./ Artists Rights Society, New York

3 ⁄8

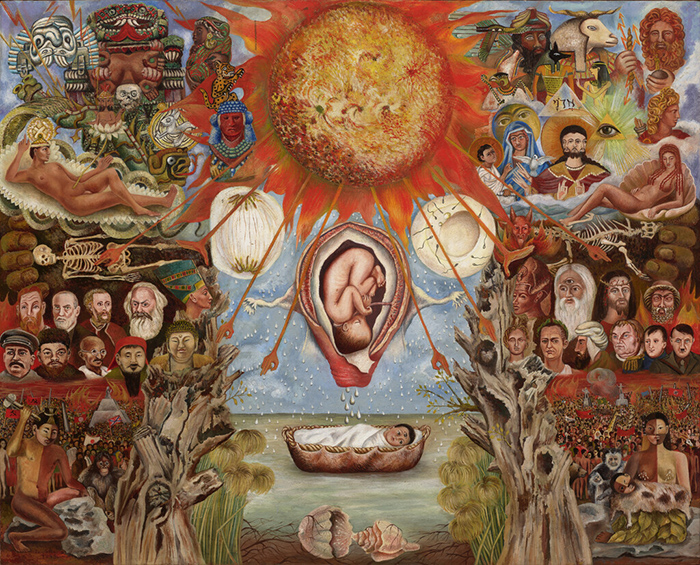

Frida Kahlo, Moses, 1945, oil on Masonite, private collection. © 2025 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, Mexico, D.F./ Artists Rights Society, New York.

4 ⁄8

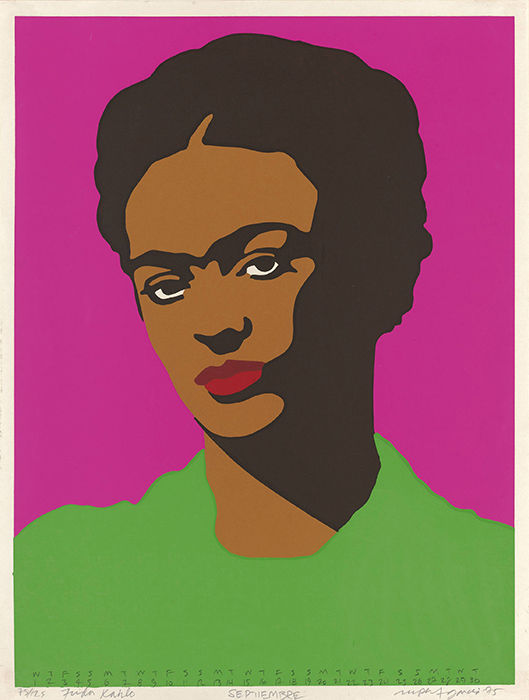

Rupert Garcia, Frida Kahlo (September), from Galeria de la Raza 1975 Calendario, 1975, screenprint on paper, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, De Young Museum, museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment. © Rupert García, courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco. Image © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

5 ⁄8

Mary McCartney, Being Frida, London, 2000, giclée print, courtesy Mary McCartney Studio. © Mary McCartney.

6 ⁄8

Martine Gutierrez, Demons, Tlazoteotl ‘Eather of Filth,' p92 from Indigenous Woman, 2018, c-print with hand-painted artist frame, RYAN LEE Gallery. © Martine Gutierrez, courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

7 ⁄8

Yasumasa Morimura, An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (Hand-Shaped Earring), color photograph on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Art, gift of funds from Beverly Grossman, 2010.25. ©Yasumasa Morimura, courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

8 ⁄8

Nickolas Muray, Frida with her Pet Eagle, Coyoacán, 1939, printed 2024, inkjet print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

“The exhibition is not a retrospective exhibition, even though we’re presenting about 35 works of Frida. But it is an investigation of how she became transformed into this global icon through the impact she exerted on these generations of artists.”

Ramírez has organized the exhibition around seven thematic sections: Construction/Self-Construction, Surrealist Affinities, On the Other Side of the Border, Gendered Dialogues, Neo-Mexicanism, Fridamania, and Pro-Activist Legacy. These concentrations also become a chronological exploration of the generations of artists and communities who embraced Kahlo, finding aspects of her life and work that resonated with their own.

Ramírez says being able to witness this expansion of Kahlo’s influence over the decades is what inspired her to organize the exhibition this way.

“I was able to observe throughout the years how this process unfolded, in the 1970s starting with the feminist and the Chicanos, and then in the ’80s, with the New Mexicanist and the LGBQT community, and then how it unfolded into the present,” she describes. “I thought it would be a far more interesting way to look at Frida through the lens of these five generations of artists. So this exhibition is the first of its kind to really look at that in a comprehensive way.”

The journey begins long before Frida became that icon with a focus on Kahlo’s “Construction/Self-Construction” of her image and identity in her own art.

“The starting point for the exhibition is the notion that everything in Frida was self-constructed. Every self-portrait, every gesture that she portrays in the self-portraits, every image, the way that she composes herself, everything is deliberate,” explains Ramírez, noting that Frida’s self is also very multifaceted, as painter, intellectual, avant garde artist, and devoted wife to Diego Rivera.

She is the narrator and creator of her own story, and in some ways becomes her own muse.

And this ability to lay herself bare in front of the viewer on her own terms would inspire generations of artists but also act as a kind of “template that other people can inhabit.”

This first section along with the second “Surrealist Affinities” examines Kahlo’s own artwork as well as those contemporary artists who influenced her and were working in some of the same cultural circles.

The middle of the exhibition explores how Kahlo was “reborn” in the 1970s and into the 90s as different communities including Chicano, feminist, LGBT, and disability artists and activists referenced her, pushing her closer to icon status.

“All of the artists in the exhibition have acknowledged their relationship to her work, and to her,” describes Ramírez of the approximately 80 artists presented along with Kahlo’s work. “They recognize her as an interlocutor and a core reference for their work.”

Later in the exhibition viewers might find themselves overwhelmed by just what iconography means in the contemporary, global world, as the section “Fridamania” unleashes all that our Frida love has wrought with popular culture depictions, a kind of universe of Frida. Ramírez charged Dr. Arden Decker, ICAA associate director, with amassing a gallery-sized collection of Frida commercial merchandise and handmade pieces. For all the mass-produced t-shirts, mugs, and dolls, “Fridamania” also offers pieces of hand-made folk art that illustrate the real, emotional connection each creator has with Frida’s art and life.

“She continues to be Frida, and the values that she stands for continue to be alive,” muses Ramírez, adding that it’s not just artists. “Whether I’m talking to the guard at the museum or the woman who sells the tickets, or a friend or a relative, when I bring up Frida, some people start crying. It’s amazing, the emotional connection that they have to her.”

—TARRA GAINES