Renowned Himalayan artist Tsherin Sherpa created the first work of his provocative Spirits series in 2009. In the painting, a wrathful three-eyed deity with fanged teeth stares out at the viewer with a bewildered expression. He squats against a gold background, wearing a crown adorned with skulls and a pair of tighty-whities. Even deities have to don underwear in this strange new world. Looking closer, the viewer will see that the spirit’s body is a mosaic of tiny little photographs of Tibetan people dispersed around the world.

Referring to the first work in the series, Spirit (2009), Owen Duffy, the Nancy C. Allen Curator and Director of Exhibitions at Asia Society, explains that it is around this time that Sherpa made a transition from being a traditional painter to being a contemporary artist. Born in Nepal to an ethnically Tibetan family, Sherpa apprenticed with his father, a master thangka painter, from the age of 13 in Kathmandu. He learned all the techniques one needed to know to execute a traditional religious painting, with its schematic rendering of spaces and its myriad symbolic representations. Two works by Sherpa’s father are included in this exhibition to give context to the artist’s starting point. Sherpa moved to California in 1998 and began working on religious paintings for monasteries in the Bay Area. “Eventually he realized there is a possibility of being rooted in tradition but exploring something that’s more of a unique artistic voice,” says Duffy. “Around 2009 he developed this idea of the ‘Spirit’ character and that is what this exhibition really focuses on.”

In the tongue-in-cheek painting Shambhala (2013), a gray-hued Spirit, drained of all color and power, holds a placard with a number and the Tibetan word for Shangri-La. He is posing for a mugshot. A few vivid butterflies and small flickering flames only serve to emphasize the colorlessness of the imprisoned Spirit. “It’s a work that directly suggests the daily occurrence of running into challenging situations where Tibetans’ movements are controlled,” says Duffy. “That’s something Sherpa very much feels and has seen, the different ways Tibet has been occupied, oppressed, and culturally repressed.”

An absurdist, occasionally irreverent, sense of humor pervades Sherpa’s works. Many of the Spirits prefer polka-dot underwear, a cheeky nod to Damien Hirst’s iconic spot paintings. In Oh My God-ness! (2009), the squatting Spirit is burdened with a large halo-like black disk filled with logos from pop culture and commerce, from McDonald’s golden arch to Snoopy, Bart Simpson, Coca-Cola, and CNN. The figure seems dwarfed by the weight of the disk. Sherpa revisits the same subject in OMG (2016), but this time the squatting figure, dripping purple and tattooed with cartoonish imagery, dominates the frame. His head is crowned with snakes, a symbol of power and authority. In Untitled (2012), the orb of logos reappears in gold, but this time the Spirit stands confidently in front, ready to take on the world. In the humorously titled Staying Alive (Too Sexy to Die) (2011), a monochromatic figure strikes John Travolta’s famous pose from Saturday Night Fever. The Spirit is having a bit of fun, but even as he thrusts one finger up to the sky, the other hand makes the gesture of the karana mudra, warding off the negative obstacles that might still stand in his way. In all four paintings, the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the polka-dot underwear, highlighting the underlying absurdity of the situations in which these spirits find themselves in the modern world.

1 ⁄6

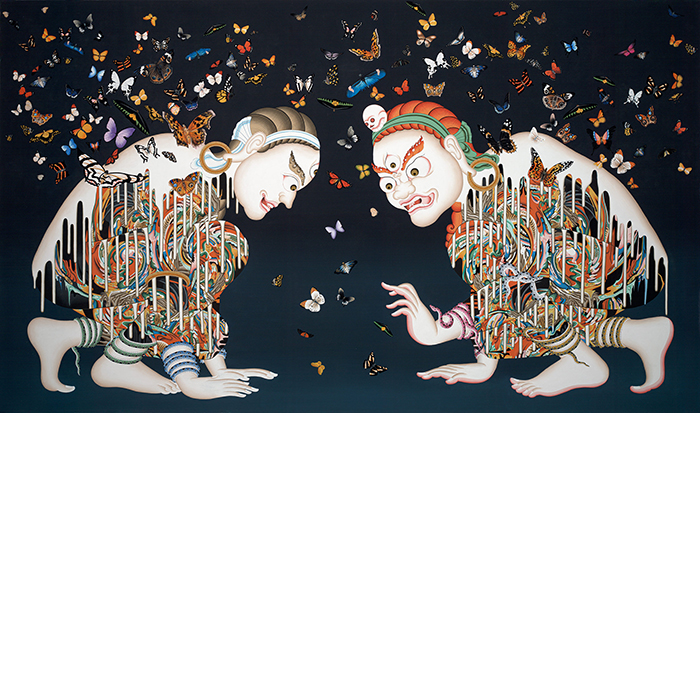

Spirits (Metamorphosis), 2019-20, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal, 1968), acrylic and ink on canvas. Collection of Dolma Chonzom Bhutia.

2 ⁄6

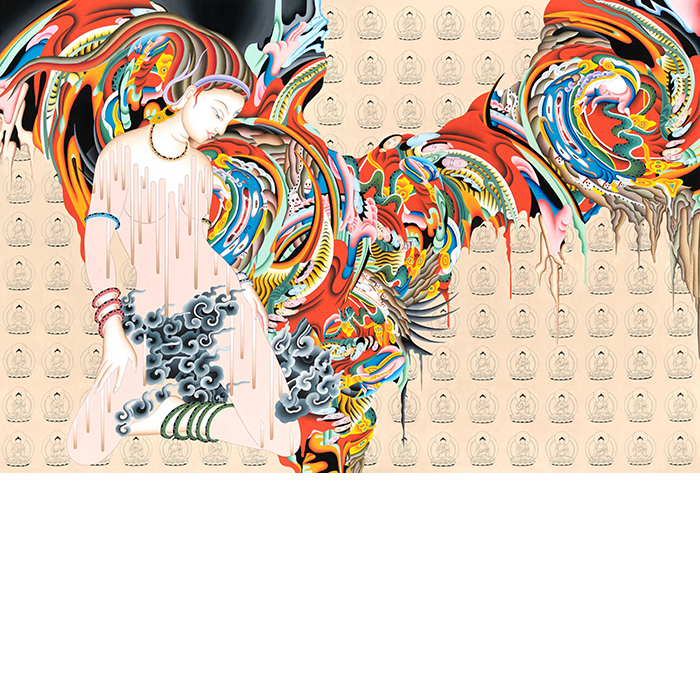

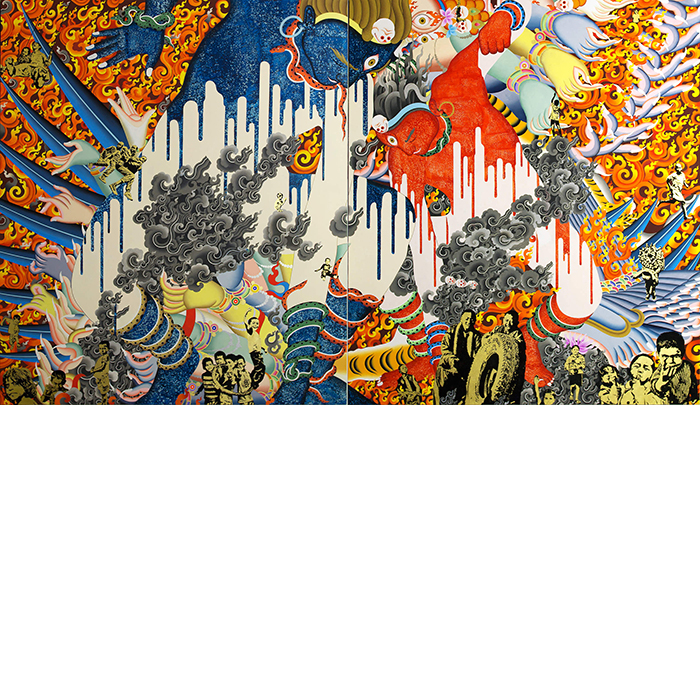

Spiritual Warrior, 2020, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal, 1968), acrylic and ink on two canvases. The Kao/Williams Family Collection

3⁄ 6

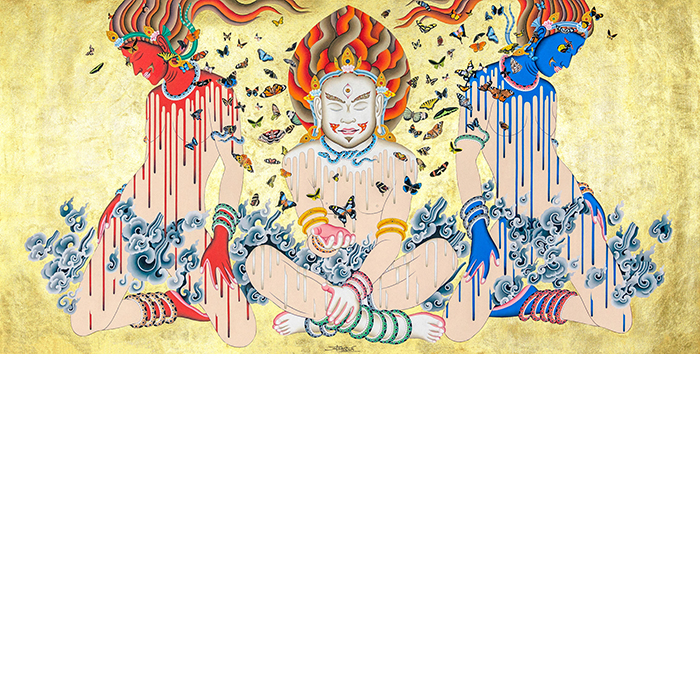

3 Wise Men, 2019, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal, 1968), gold leaf, acrylic, and ink on canvas. Collection of Seema Paul, California

4 ⁄6

Skippers (Kneedeep), 2019-20, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal, 1968), in collaboration with Regal Studios, Kathmandu, gold leaf, acrylic and ink on fiberglass. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2021.66, Photo by David Stover

5 ⁄6

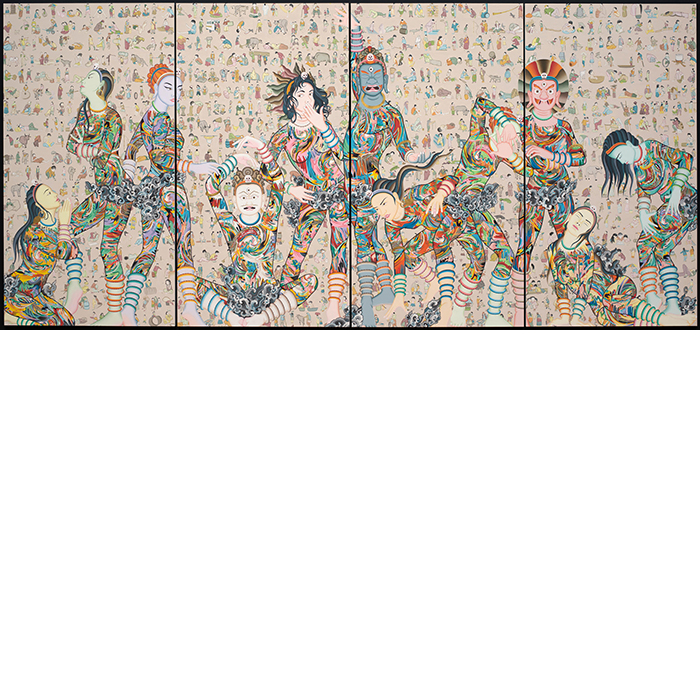

Himalayan Spirits, 2021, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal, 1968), gold, acrylic, and ink on four canvases. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2022.74a-d.

6 ⁄6

All Things Considered, 2014, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal, 1968), pale gold leaf, acrylic, and ink on two canvases. Elaine W. Ng and Fabio Rossi Collection

Sherpa worked with local metalsmiths skilled in repoussé to hammer out his designs. The animals of the Zodiac circle the bottom layer while Sherpa’s own Spirit characters flash the peace sign on the higher levels. The original work included debris from the earthquake. The Houston iteration uses locally salvaged material, including gravel from Asia Society’s garden. Visitors will be able to write their own wishes which will be inserted into the mandala’s tiers.

Duffy is also excited to show three large hand-weaved hanging carpets, collaborations between Sherpa and the traditional artisans of Mt. Refuge, a design studio in Kathmandu. “They make high-end carpets with traditional methods, very beautiful and exquisite,” says Duffy. “It’s a way of providing a platform, bringing the work of traditional artists to the forefront and ensuring they have a sense of community and economic income. Tsherin is really trying to use his stature as an international artist to create lots of visibility for artists in Nepal.”

In Spirits (Metamorphosis) (2019-20), the ever-present butterflies are now swarming in a kaleidoscopic array of colors. Two spirits, their liquifying pigmentation transformed into vibrant patterns and motifs that seem to invoke protective powers, look intently at the butterflies, contemplating this vital symbol of transformation as they go through their own.

The grand finale of the exhibition is one of Sherpa’s largest paintings to date. Himalayan Spirits (2021) represents a cast of Spirit characters as if they were in a Bollywood poster. Hundreds of nostalgic vignettes from daily life in Nepal form the background of the painting–a little boy in a bathtub, a man making tea, a mother braiding her daughter’s hair. The eleven Spirits, each with a distinct identity and personality, unite in a single composition. The diversity within this group of Spirits is unprecedented in Sherpa’s works. “In terms of their features, expressions, attitude, their clothing, hair, and skin color, there’s a real sense of variety baked into this painting,” observes Duffy. “The cast is meant to be rounded out. Sherpa imagined the group of eleven as an incomplete ensemble of twelve. The visitor becomes the twelfth Spirit.”

—SHERRY CHENG