“I was thinking about young Native artists and what would be inspirational and important for them as a road map,” said Wendy Red Star, curator of Native America: In Translation. The lens-based exhibition she curated features nine contemporary Indigenous artists whose wide-ranging practices in photography, installation, performance art, collage, multi-media assemblage, and video contemplate Native existence past, present, and future.

It was important to Red Star to showcase intergenerational artists. Two of the artists, Alan Michelson and Rebecca Belmore, have been driving forces in Native American art for decades. Michelson draws upon historical memory and Indigenous philosophy, taking deep-dive archival research as a starting point to present an encompassing narrative that includes Indigenous histories.

In the six-panel work Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), Michelson takes French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon’s iconic bust of George Washington, who the Iroquois called “Town Destroyer,” and projects onto it historical maps, documents, site markers, and other materials that trace the course of Washington’s brutal scorched-earth campaign against the Iroquois in 1779. The story of invasion, forced eviction, and devastation plays out over Washington’s face, challenging what Michelson calls American amnesia and denial.

Youngest of the nine artists, Martine Gutierrez constructs a glamorous high-fashion world through her staged self-portraits. She famously said, “no one was going to put me on the cover of a Paris fashion magazine, so I thought, I’m going to make my own.” Her 2018 project Indigenous Woman took the form of a 124-page fashion magazine. It’s a humorously performative art book. “Every aspect of it was made by her,” says Klemm. The artist is producer, model, photographer, stylist, and creative director.

With style and panache, Gutierrez uses the masquerade to question ideas of gender and identity. In an advertisement for “Identity Boots,” she poses nude in go-go boots, gender symbols taped all over her body. The wild and fun set of images called “Queer Rage” is a perfect synthesis of teen angst and high fashion. Throw in her father’s Guatemalan Mayan fabrics, some wild jungle animals, and her collection of American Girl dolls, the fun DIY elements become beautiful expressions of self.

1 ⁄8

Rebecca Belmore, matriarch, 2018, from the series nindinawemaganidog (all of my relations), Photograph by Henri Robidea, archival pigment print, 56 x 42 in., Courtesy of the artist

2 ⁄8

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake Fishing, undated, 10-piece collage of digital prints, pencil, paint on paper, 18 x 29.7 in., Courtesy of the Kimowan Metchewais [McLain] Collection, National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution

3 ⁄8

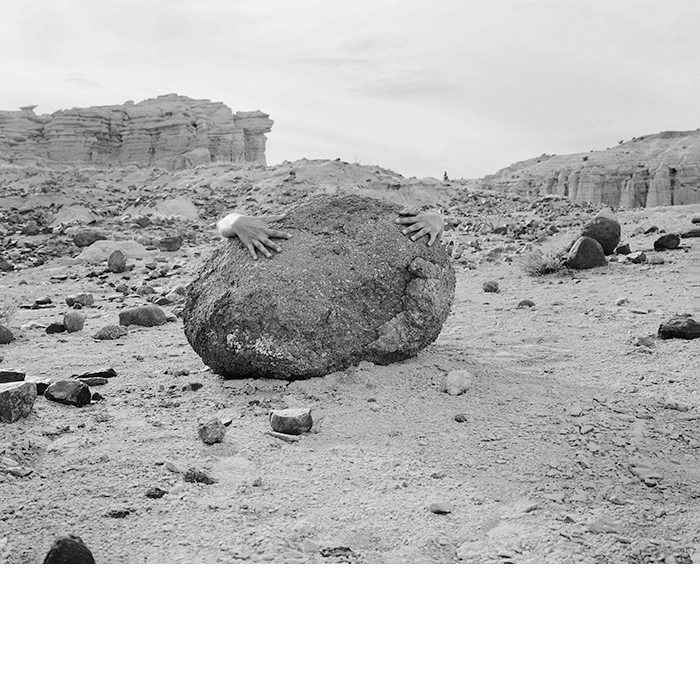

Koyoltzintli , Spider Woman Embrace, Abiquiu, New Mexico, 2019, from the series MEDA, 2017–19, archival pigment print, 24 x 30 in., Courtesy of the artist

4 ⁄8

Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland, Molly Alexie and her children after a harvest of beach greens in Quinhagak, Alaska, 2018, archival pigment print, 20 x 30 in., Courtesy of the artist

5 ⁄8

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, Imagine Life-Size, and I’m Tyra, p66–67 from the series Indigenous Woman, 2018, archival pigment print, 42 x 28 in., Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

6 ⁄8

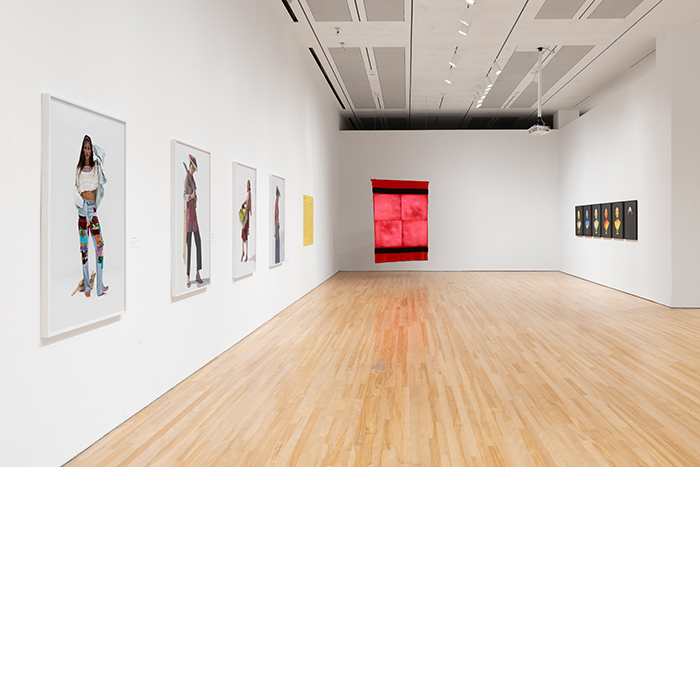

Installation view of Marianne Nicolson, Widzotłants gwayułalatł? Where Are We Going…What Is to Become of Us?, in Native America: In Translation at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, August 4, 2024–January 5, 2025

7 ⁄8

Installation view of Kimowan Metchewais, Indian Handsign, in Native America: In Translation at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, August 4, 2024–January 5, 2025

8 ⁄8

Installation view of works by Martine Gutierrez, from the series Indigenous Women and Alan Michelson, Pehin Hanska ktepi (They killed Long Hair) and Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), in Native America: In Translation at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, August 4, 2024–January 5, 2025

Throughout the exhibition there is a sense that history is present. “I think the artists are trying to show the everyday presence of histories on people, and how they are creating beautiful communities and art out of everyday life,” says Klemm.

This is true of Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland, who does not think of herself as an artist, but rather a subsistence hunter-fisher-gatherer. The photographs in this exhibition are part of an anthropological and documentary project funded by the National Science Foundation to study variations in the diets of native communities in the Bering Sea. She helps small, isolated communities in this area of Alaska to re-embrace foraging techniques to subsist and flourish. The photographs feel intimate and soulful. “That’s one of the things that’s so beautiful about it,” says Klemm. “It really is a portrait of contemporary Native life, and what’s important to Native people in thinking about the land, about subsistence, and about ways to use Native modes of being to propel cultures and societies forward.”

Marianne Nicolson considers herself a cultural researcher and historian as well as an advocate for Indigenous land rights. Her light and glass installation projects powerful archival images and symbols of the Kwakwaka’wakw people onto the gallery space. Meanwhile, the artist Koyoltzintli, descendant of the Manta people of Ecuador, uses myth to document endangered Indigenous oral traditions. Her black and white photos channel origin myths through Spider Woman and Sky Woman, using her body within nature to express lived understandings of memory.

Guadalupe Maravilla, who was part of the first wave of unaccompanied, undocumented children to cross the border during the Salvadoran Civil War, survived the trauma of 40 days of traveling and being passed from coyote to coyote when he was only 8 years old, and later on survived his fight with colon cancer. His retablos are a kind of protection and way of healing, devotional objects imbued with great power.

And finally, the first artist Red Star selected for this exhibition and the only artist who is no longer living, Kimowan Metchewais, “the artists’ artist,” encapsulates with his works all the enduring themes in this exhibition–land, language, memory, and healing. Metchewais died in 2011 after his decades long fight with a brain tumor. He gifted his enormous collection of polaroids to the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, some of which are shown in a video projection for the exhibition.

-SHERRY CHENG