Who, or what, makes a life? Artist Kinji Akagawa has built his by collaborating with others.

Art Making as Life Making: Kinji Akagawa at Tamarind, on view April 23 through Oct. 30 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, showcases the meaning and impact of collaboration in this renowned artist’s life. The show includes Akagawa’s own lithographs and those he printed for artists in residence at Tamarind Institute (then Tamarind Workshop) including Ruth Asawa, Herbert Bayer, and Jose Luis Cueva. All in all, the show features over 40 works from the Carter’s collection of more than 2,500 Tamarind prints.

Born in Tokyo, Akagawa came to the US in 1953 and in 1965, at 25 years old, he embarked on a fellowship to train as a printer at Tamarind when the workshop was still in Los Angeles (in 1970, Tamarind moved to its current location in Albuquerque at the University of New Mexico). Akagawa was the workshop’s first international printer, collaborating with more than a dozen leading artists of the time. Printing for resident artists during the day, he would work on his own prints at night, creating his Black Rainbow series, among others.

Prints on view in Art Making as Life Making include Asawa’s Aiko, a portrait of a girl in profile wearing a delicate headscarf; selections from Bayer’s Monochromes series, geometric gradients that play with color and light; and impressions of Asawa’s own exploratory marks, tone, texture, and text.

He explains that as a young person, “a young punk,” his ideas of America came from his experiences with the culture, the language, and the major political events of the time, such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Jr., and Martin Luther King, Jr. And through his experiences at Tamarind with new critics and new intellectuals, as well as artists, philosophers, and poets, Akagawa came to understand American democracy through the democratic nature of printmaking which impressed upon him the importance of aesthetic practice in a community.

The communal environment at Tamarind has had a profound impact on Akagawa’s philosophies of art and life, and his generosity in the collaborative process is evident through his spirited conversations, humor, and cherished relationships.

1 ⁄6

Kengiro Azuma (b. 1926), printed by Kinji

Akagawa (b. 1940), Nothingness, 1965, lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1965.223, © Kengiro Azuma.

2 ⁄6

George Sugarman (1912–1999), printed by Kinji Akagawa (b. 1940), Red, White, and Blue, 1965, lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1965.329, © Estate of George Sugarman/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

3⁄ 6

Herbert Bayer (1900–1985), printed by Kinji Akagawa (b. 1940), Untitled (8 Monochromes VIII), 1965, lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1965.354.9, © Estate of Herbert Bayer /Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

4 ⁄6

Herbert Bayer (1900–1985), printed by Kinji Akagawa (b. 1940), Untitled (8 Monochromes V), 1965, lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1965.354.6, © Estate of Herbert Bayer / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

5 ⁄6

George Earl Ortman (1926–2015), printed by Kinji Akagawa (b. 1940), Two (Oaxaca XIV), 1966, lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1966.203.14, © George Ortman

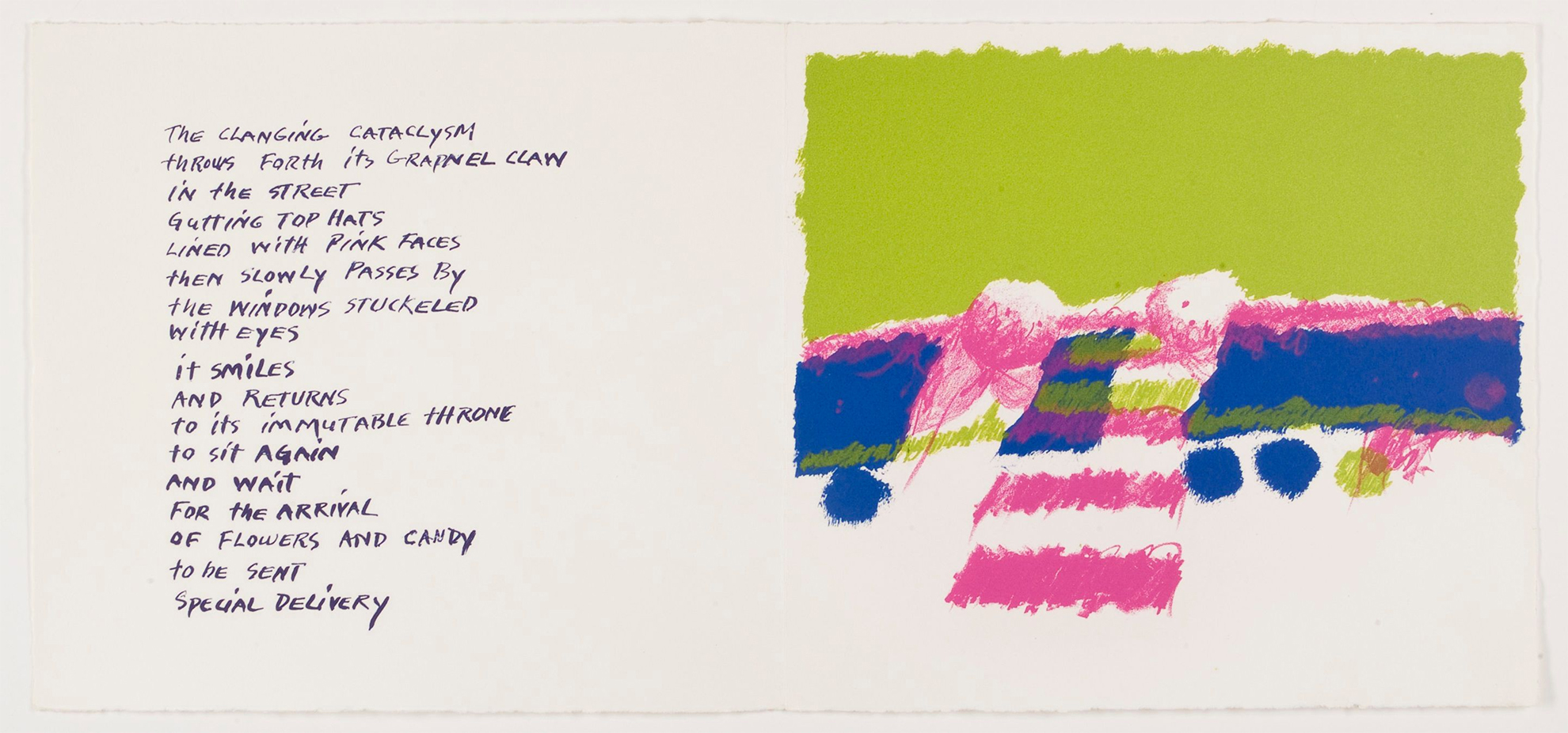

6 ⁄6

Kinji Akagawa (b. 1940), The Clanging Cataclysm (Pink Jelly II), 1966, lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1966.198.3, © 1965 Kinji Akagawa.

Akagawa also trained at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, went on to earn his MFA from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and taught sculpture, printmaking, photography, video, installation, and conceptual art at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD). He found that he loved Midwestern life and soon learned that it loves him.

He moved away from the gallery and museum scene and today is recognized as a pioneer of public art, which he finds to be much more open and socially oriented; some readers may be familiar with his “Bayou Sculpture” (1985) in Houston. He received the McKnight Foundation Distinguished Artist Award in 2007 and continues to acquire knowledge by remaining curious.

“Without reviewing and reexamining our everyday life, art is impossible,” he says.

—NANCY ZASTUDIL