Salvador Dali, The Accommodations of Desire, 1929

oil and cut-and-pasted printed paper on cardboard

8 3/4 x 13 3/4 in (22.2 x 34.9 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sometimes artists dream of success and fame. And, sometimes, it’s the dreams themselves that make the artist famous.

“Salvador Dalí was an incredibly talented painter, revealing from a young age his ability to successfully adopt the styles of his predecessors, including Impressionism, Cubism, and Neoclassicism,” says Shelley DeMaria, curatorial assistant at the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University who, with the Linda P. and William A. Custard Director of the Meadows Museum Dr. Mark Roglán, co-curated Dalí: Poetics of the Small, on view Sept. 9–Dec. 9. “The challenge for him, as I see it, was to find the hook that would set him apart from others and ensure his lasting fame.”

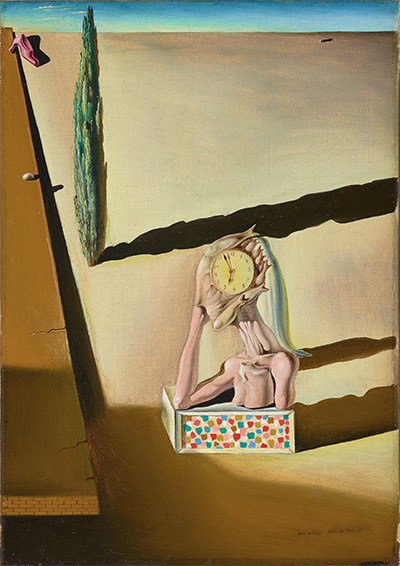

oil on canvas

10 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (26.15 x 18.5 cm)

Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas

That hook turned out to be his involvement with Surrealism. From 1929 to 1939, Dalí completed nearly two hundred paintings, developing and mastering his now signature style of incorporating elements of photography and collage in his paintings. Early in his life, he faced tragedy when his brother died and, later, his mother. These and other formative experiences, whether artistic, sexual, or political, impacted the artist’s dreams and subconscious activity, allowing him to create his most intriguing—and often disturbing—art works.

In the mainstream world, Dalí is perhaps best known for his eccentric personal style, including his long, pencil thin, curved moustache, and “weird” paintings, such as his 1931 work, The Persistence of Memory (often incorrectly referred to as Melting Clocks), but many may not be aware of his skill as a draftsman or his classical influences. Dalí died in 1989, at the age of 84. Throughout his life, he worked with a range of other artists, filmmakers, and cultural creatives from Man Ray to Walt Disney. Numerous modern and contemporary artists cite Dalí as a major inspiration.

Plans for Poetics of the Small, which showcases almost two dozen paintings created by Dalí between 1929-1936, began after the Meadows acquired the small-scale 1930 painting The Fish Man (L’homme poisson) in 2014, filling a gap in the museum’s collection. The painting, just 10 1⁄2 x 7 1⁄2 inches, depicts the bust of a sinewy figure, whose head is made of stacked fish, in a dry, vast landscape. Shadows run dark and long off the edges of the canvas.

The painting has drawn interest in the popular and academic spheres. In near pristine condition when the Meadows acquired it, the Kimbell Art Museum conservation department conducted a technical analysis of the work, taking X-ray and infrared images as well as pigment samples.

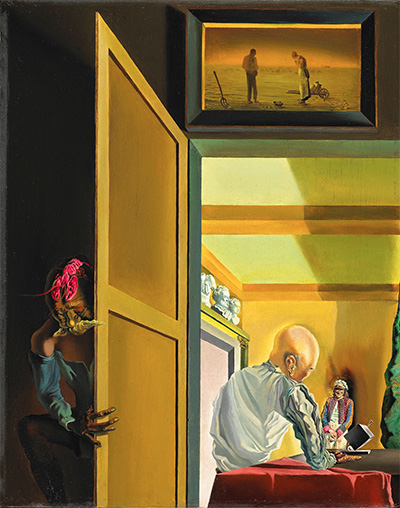

Gala and the Angelus of Millet Immediately Preceding the Arrival of the Conic Anamorphoses,

1933

oil on wood

9 1/2 x 7 1/2 inc. (24.2 x 19.2 cm)

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

“Our exhibition gives focus to the small scale of the paintings—the largest works on view will measure just over 13 inches and the smallest just 3 ½ x 2 ¾ inches,” says DeMaria. “The size of the paintings is a characteristic that is often overlooked, since many of us know the artist’s works primarily through reproductions, which can sometimes be larger than the works themselves. For example, Dalí’s most famous painting, The Persistence of Memory, falls within this small-scale category—I think this fact surprises many.” (Count me as one of them.)

Other works in the show are on loan from public institutions and private collections including the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida and the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres, Spain. A concurrent exhibition, Dalí’s Aliyah: A Moment in Jewish History, features a rare complete set of 25 lithographic prints, gifted to the Meadows Museum last year, created from Dalí’s mixed-media paintings which were commissioned in 1966 by Samuel Shore, head of Shorewood Publishers in New York.

Although it is difficult to explain exactly why Dalí painted so small, in her catalogue essay, DeMaria explains that “the artist’s employment of a small-scale format was inherently connected to his interest in collage, a medium traditionally small in proportion due to the customarily small size of the sourced materials” (think of various collaged texts cut from newspapers and books). By precisely painting elements of collage, juxtaposing seemingly unrelated images, playing with scale, and incorporating photographic visual “tricks,” Dalí mastered the effect of “destabilization of reality,” a main principle of the Surrealist movement—one he made all his own.

“I believe it was, in part, his desire to distinguish himself that led him to closely consider the merits and potentials of photography and collage,” she says.

Goldfinch (Cardinal, cardinal!), c. 1934

Oil and tempera on wood panel

6 1/4 x 8 1/2 in. (15.87 x 21.74 cm)

Munson William Proctor Institute, Utica

DeMaria also writes that Dalí was fascinated with photography because of its “anti-artistic characteristics” and because he was attracted to “the objectivity of mechanical instruments,” furthering explaining that his interest was more about borrowing from other mediums rather than fully adopting them. Roglán notes it may have been Dali’s admiration for Johannes Vermeer, the 17th-century Dutch painter, known for his use of light in his paintings, but who also worked small and in a photographic manner.

“By gathering together a group of these paintings, we aim to highlight how the artist employed a small scale to further advance his artistic language,” DeMaria explains. “I hope the exhibition will facilitate slow and thoughtful viewing of the works because, even though they can be tiny, they are full of rich iconography, fascinating narratives, and an impressively precise technique.”

—NANCY ZASTUDIL