As Blue Star Gentrifies, viagra Artistic Energy Branches Out Across Town

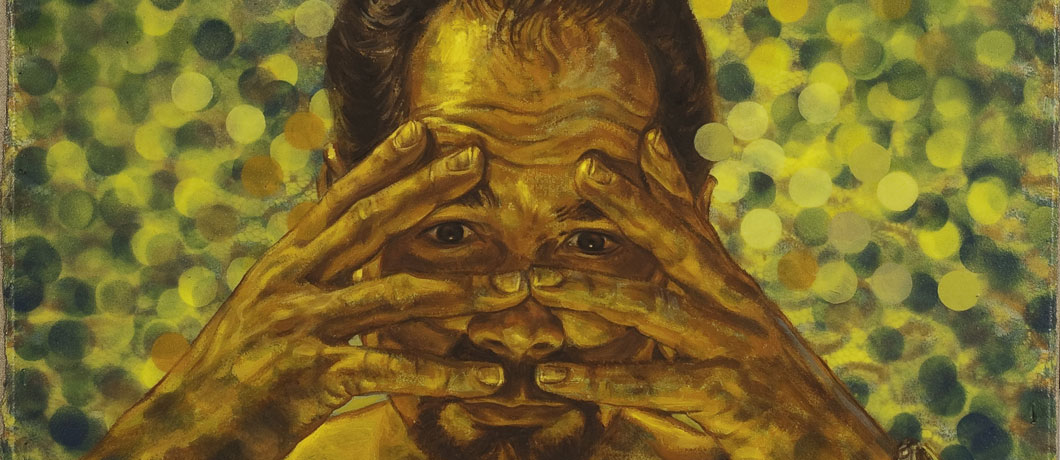

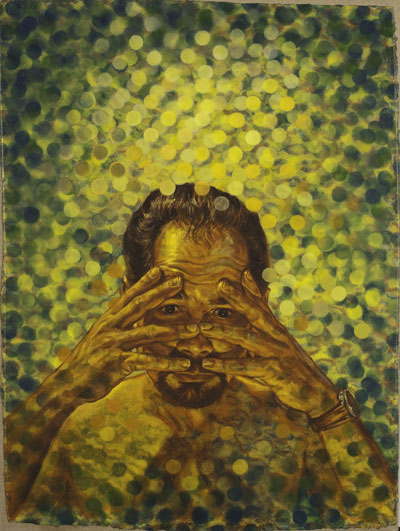

IMAGE ABOVE: Angel Rodriguez-Diaz, American, born 1955, Circulos de Confusion (Circles of Confusion), 1993. Oil on paper on linen. San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by Edward A. Fest, by exchange, 95.16. Photography by Peggy Tenison.

After nearly 30 years, gentrification has finally taken over the Blue Star Arts Complex, long the center of San Antonio’s contemporary art scene. Though busier than ever as a launching point for runners and bicyclists headed to the newly opened Mission Reach of the San Antonio River, the Blue Star has pushed out smaller, artist-run spaces and theaters in favor of bars, restaurants, a hair salon, bike rentals and upscale apartments.

On the bright side, the contemporary art diaspora has spread the city’s creative energy to other long-neglected neighborhoods.

In 1986, artists rolled up their sleeves and provided the sweat equity to clean up a long-abandoned 1920s warehouse to create the Blue Star Art Space. At the time, it was hard to find the work of local artists in local museums, and less than a handful of spaces showed contemporary art. But a lot has changed in the past three decades.

The old warehouse that didn’t have air conditioning until the advent of the 21st century has evolved into the Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum. The University of Texas at San Antonio, just getting going in the early 1980s, now produces a steady supply of MFAs, who often take a DIY approach to their careers, transforming other areas of the city such as South Flores, Tobin Hill, Beacon Hill and Fredericksburg Road into havens for artists. A major advantage San Antonio has over other Texas cities is lots of relatively affordable real estate — especially old, neglected commercial spaces and warehouses.

Long-time Blue Star director Bill FitzGibbons stepped down last summer to devote more time to his public art projects with LED lights, such as the popular Light Channels that illuminate two underpasses at Commerce and Houston Streets, reconnecting downtown to the East Side, which was cut off when the city surrounded its core with elevated expressways in the 1960s.

Although the city had to disguise “public art” as “design enhancement” when it adopted a percent-for-art ordinance in the 1990s, civic art has earned popular support, FitzGibbons says.

Photography by Peggy Tenison

“Though city council was not supportive, really hostile at first, public art has become something that the public wants,” he says. “With projects like Light Channels and the Donald Lipski sunfish along the Mission Reach, people finally have the chance to see how public art can transform a neighborhood.”

Artpace, the international artist residency program founded by Linda Pace in 1993, attracts big-name curators and artists to South Texas and has launched several San Antonio artists into the national spotlight. Both the San Antonio Museum of Art and the McNay Art Museum have contemporary curators and avidly collect work made by Texas, national and international artists. The Southwest School of Art, known for its community art classes, is on the verge of offering a BFA.

Franco Mondini-Ruiz, a former lawyer whose art career took off when he was selected for the Whitney Biennial in 2000, says the city’s art scene is still reeling from the death of Linda Pace in 2007.

“The millions she invested in elevating San Antonio art and her prestige in the global art scene put us on the map for about ten golden years,” Mondini-Ruiz says. “The great accomplishment of my generation, of which I was a fortunate beneficiary along with artists such as Dario Robleto, Jesse Amado and Chuck Ramirez, has for the most part atrophied. The capital investment, professional promotion and internationally-connected infrastructure are no longer in place to create future San Antonio Rome Prize winners and Whitney biennial alums like me.”

Artist Nate Cassie says the city is a attracting a lot of young artists, but the question is how long they will stay when commercial and vocational opportunities are so limited.

“I think the draw is multiple – strong artist community, low cost of living, interesting artist-run spaces, though these are always in flux, and institutions like Artpace, Blue Star and the Southwest School of Art,” Cassie says. “The downside of the grassroots scene is money, a small collector base and small cultural investments relative to the impact of the arts on the larger community and economy.”

Linda Pace and then-director Kathryn Kanjo infused Artpace with vision and energy that garnered international acclaim while bringing more recognition to San Antonio artists. However, under a succession of short-term directors, Artpace has opened up its local residency space to Dallas, Houston and Austin artists, who probably don’t need as much career-building assistance.

Like the rest of the globe, the San Antonio art scene is still trying to recover from the effects of the Great Recession. Artists everywhere seem to have given up trying to change the world in favor of trying to pay the rent.

“There is a very grassroots return to nature, good food, low art productivity, homesteading and pioneer spirit in the current San Antonio art scene,” Mondini-Ruiz says. “The pursuit of fame, glamour and fortune is passé.”

David Rubin, the San Antonio Museum of Art’s contemporary curator, sees San Antonio artists “pursuing many of the same interests as elsewhere, such as abstract painting, social and political art, and digital and new media explorations,” he says. “Among some artists there is a strong conceptual bent, while others prefer emotional and visceral approaches.”

In the contemporary galleries at SAMA, Rubin says works by San Antonio artists reveal shared interests in found-object assemblage, portraiture and manipulation of images. Some 22 works by San Antonio artists can be seen in TX 13: Spotlight on Texas Artists in the Contemporary Collection through Nov. 9 at SAMA, and about 20 of Rubin’s conversations with local artists are on YouTube. (Ironically, SAMA sparked the Blue Star uprising when it canceled a show of San Antonio artists in 1986.)

Paula Owen, the Southwest School of Art’s president, says the San Antonio art scene is eclectic, energetic and in many ways still emerging, though in others it’s quite sophisticated. San Antonio’s rich history and the blending of Spanish and German cultures give the city a cosmopolitan character.

“Due to our proximity to Mexico and demographic makeup, we enjoy a unique environment in which to think and create,” Owen says. “It’s still very grassroots-y and open to newcomers and new ideas even as it shifts into slightly higher gear.”

The Russell Hill Rogers Galleries at the Navarro Campus of the SSA, under the direction of Kathy Armstrong, consistently mount some of the city’s best contemporary art shows. The McNay Art Museum’s Stieren Wing has given the state’s first private modern art museum a world-class facility for mostly traveling exhibits, though the focus is on local artists in Artists Looking at Art lectures and on contemporary exhibits in the ArtMatters series. UTSA presents contemporary shows at its 1604 Campus gallery in the art building and downtown at the Institute of Texan Cultures. But the UTSA Satellite Space has moved out of its long-time home in the Blue Star Arts Complex into a new, 4,000-square-foot space in the nearby Say Si building at 1518 S. Alamo.

While the Blue Star has lost several galleries, new spaces have opened. Mockingbird Handprints specializes in textile art and is operated by artists Jane Bishop and Paula Cox. Susan Oliver Heard opened The Cinnabar. Robert Hughes has taken over the space vacated by Joan Grona. The venerable San Angel Folk Art remains at Blue Star along with some artist-run spaces such as Hello Studio and Kevin Saunders Photography.

The Blue Star is still the center of First Friday, but other nearby galleries are worth seeking out. Sala Diaz, an artist-directed non-profit space in one-half of an old duplex, and Unit B, are as much local artist community centers as galleries on Stieren Street. Two local artists using the non de plumes Margaret L. Honeytruffle and Alice Thud have opened the tartly tongue-in-cheek Epitome Institute at 222 Roosevelt Ave. in Southtown.

However, the South Flores Arts District, aka the Lone Star Arts District, is on the rise with its Second Saturday extravaganza. South Flores is anchored by the Gallista Gallery, the city’s primary Chicano art gallery, and Andy Benavides’ One9Zero6 Gallery in the same building with the Fl!ght Gallery. Around the corner is FitzGibbons’ Lone Star Studios. Also in the area are the Lady Base Gallery, 3rd Space Art Gallery and Comminos Art Studio Gallery.

Executive Director Patti Ortiz explores the cutting edge in exhibits at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, which also presents movies, performing arts and other events. Texas A&M University-San Antonio has taken over the city’s failed attempt to establish a national Hispanic art museum, Museo Alameda, though the university promises to continue emphasizing Latino art at the venue in Market Square.

In the Deco District on Fredericksburg Road, Centro Cultural Aztlan is one of the city’s oldest Latino art organizations, sponsor of the Lowrider Festival. Down the road tucked away in a retirement complex is Bihl Haus Arts, which emphasizes local Hispanic artists in its exhibits and sponsors the On and Off Fredericksburg Road Studio Tour in February.

“Prices going up at the Blue Star have been good for us because the artists can still find affordable spaces in this neighborhood,” says Bihl Haus executive director Kellen Kee McIntyre. “We’ve been seeing a lot of new spaces popping up, such as all the artists at the Clamp Light Studios and Gallery.”

Another cluster of artist-run spaces to the northwest of the Pearl Brewery foodie mecca is featured during the Tobin Hill Second Friday Art Walk, including High Wire, Dewey Art Space and Art by Bjorn.

Rather than cluster, the city’s high-end galleries are spread out in pricier neighborhoods and suburbs. Dana Read’s first-class REM Gallery presents shows by mostly local and regional artists on the ground floor of a two-story renovated mansion near San Antonio College. Along Broadway, not far from Alamo Heights, are two of the city’s oldest contemporary art galleries, AnArte and Parchman Stremmel. Lawrence Markey near downtown on Sixth Street has a New York pedigree. Bismarck Studios Contemporary Fine Art Gallery is near Stone Oak outside Loop 1604. Easily the city’s biggest and best-designed gallery is Gallery Nord in Castle Hills. Owner Carina Gors shows local and Texas artists along with presenting music concerts and other events.

As welcome as all this activity is, FitzGibbons says San Antonio’s low income levels relative to Dallas or Houston mean developing a collector base to support it continues to be a struggle. Still, he says, the number of artist-run spaces remains the city’s greatest strength.

“Not many people thought San Antonio had a contemporary art scene when the Blue Star began,” FitzGibbons says. “But the Texas Biennial’s TX 13 exhibit has gotten notices in The New York Times and Art in America, so we’ve come a long way.”

—DAN R. GODDARD