Pete Seeger wrote the protest song “If I had a Hammer” in 1949 in support of the progressive, pro-labor movement of that era. In the sixties it became a freedom song of the civil rights movement and an inspiration to the counterculture protests led by a new generation of young people. The song is a rallying cry for justice, equality, and action.

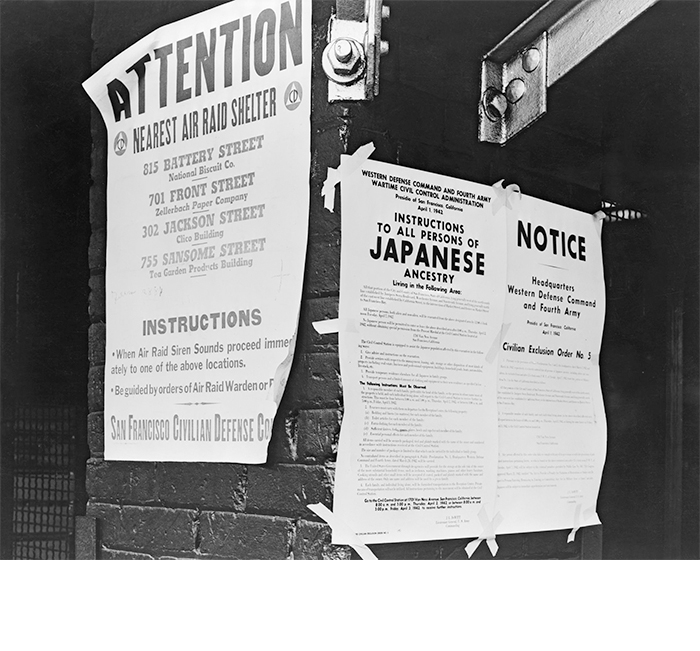

What can we still learn today from the dark episode in American history when the U.S. government forcibly incarcerated over 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry in internment camps? Two perspectives on life at Manzanar, a Japanese internment camp in California, emerge in the documentary photography of Dorothea Lange and Tōyō Miyatake. “We thought it was very important to show and contrast the very distinct perspectives of these two photographers,” says Evans. “We leave it to our viewers to consider how the bodies of work inform each other and our understanding of that historical moment.”

Lange, best-known for her searing portraits of Depression-era poverty, was hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to document the relocation experience. She struggled with both the assignment and the army authorities. A man followed her everywhere and she was not permitted to photograph the barbed wires or guard towers in the camp. The WRA took possession of Lange’s works and the majority of her photographs were impounded for the remainder of the war. One of the more than 30 images from Lange in the Fotofest exhibition shows a banner in front of a store in Oakland, CA, proclaiming “I AM AN AMERICAN.” The store’s owner had commissioned the sign the day after Pearl Harbor. He and his wife were incarcerated shortly after and never returned to Oakland.

Many of the artistic practices in this year’s FotoFest extend well beyond the photographic discipline. The works of Ho Rui An, Yazan Khalili, Ines Schaber, and Forensic Architecture move in the realms of critical art theory, philosophy, socioeconomics, data analysis, and political activism. “This is purposeful,” says Max Fields, Associate Curator and Director of Publishing at FotoFest. “Images circulate around the globe very differently than they did 50, 20, even 10 years ago. We really wanted to focus on artists who examine how the world is imaged today.”

Ho Rui An’s DASH project looks at the RAHS (Risk Assessment and Horizon Scanning) program in Singapore, a data collection program that relies on the capture of information and images from CCTV (closed-circuit television) and crowd-sourced social media clips to study and prepare for potential crises. The artist uses dash camera footage from a fatal car crash as a metaphor for the Singapore government’s use of technology to foresee dangers on the horizon, an interrogation of how photographic vision can be utilized today.

Ramallah-based artist and cultural producer Yazan Khalili considers the proliferation of images, its commodification, and its shifting meaning in his work Copy of a Copy of a Copy, an installation of a stack of 1000 posters of Suleiman Mansour’s Jamal Al Mahamel II (Camel of Burdens) is shown with a photograph of a room of iconic Palestinian posters. The original painting by Mansour featured an elderly Palestinian man carrying an eye-shaped bundle with an image of Jerusalem. The 1973 original was given to Muammar Gaddafi by the Libyan ambassador in London and thought to have been destroyed by American airstrikes on Libya in 1986. Mansour’s 2005 version (II) contains small changes in the imagery. It became one of the most iconic Palestinian paintings and a symbol of Palestinian identity. Reproductions can be seen in homes across Palestine.

1 ⁄8

Delilah Montoya, Casta 1, 2018. From the series Contemporary Casta Portraiture: Nuestra Calidad, 2018. Dye sublimation on metal, wooden curio box, laser-etching, sand, QR code. Courtesy of the artist.

2 ⁄8

Ines Schaber, Picture Mining, 2006. 9 C-prints, 6 Archival inkjet reproductions of images by Lewis Hine. Single channel video, 14 minutes 2006. Courtesy of the artist.

3 ⁄8

Dorothea Lange, “Civilian Exclusion Order Number 5, posted at First and Front streets, directing removal of persons of Japanese ancestry from San Francisco,” 1942. Archival inkjet print, Archival inkjet print, printed 2022. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, LC-USZ62-34565.

4 ⁄8

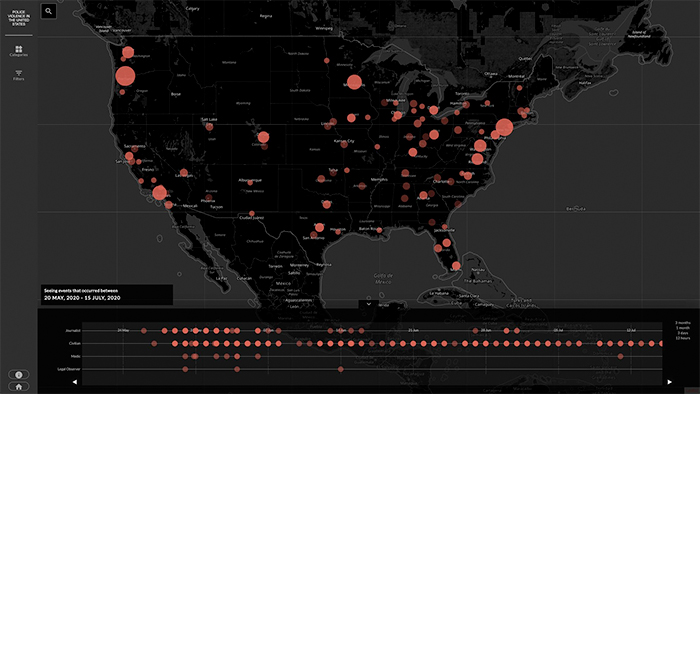

Forensic Architecture in collaboration with Bellingcat, Police Brutality at the Black Lives Matter Protests, 2020–. A view of the Police Brutality platform, Screenshot, www.forensic-architecture.org/investigation/police-brutality-at-the-black-lives-matter-protests Courtesy of Forensic Architecture © Forensic Architecture, 2022.

5 ⁄8

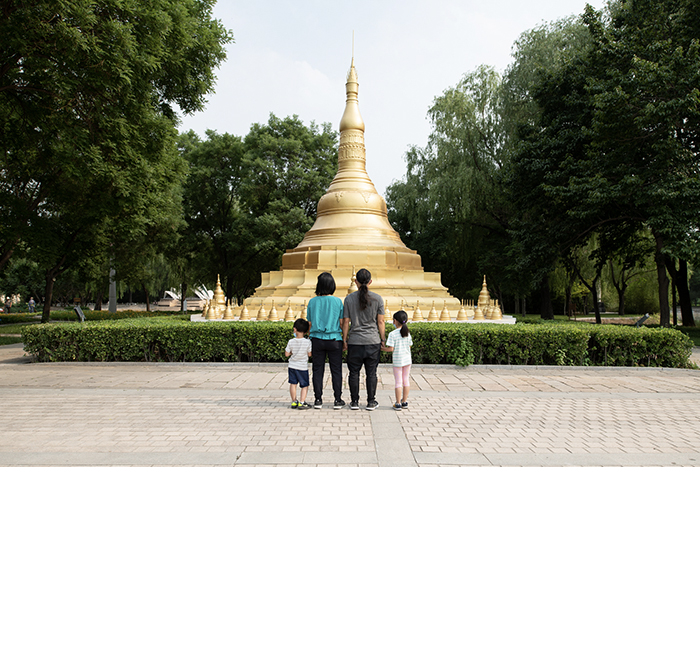

Chow and Lin, 2020:06:13, 15:49:20, 2020 From the series I want to bring you around the world, 2020–22. Archival inkjet print. Courtesy of the artists.

6 ⁄8

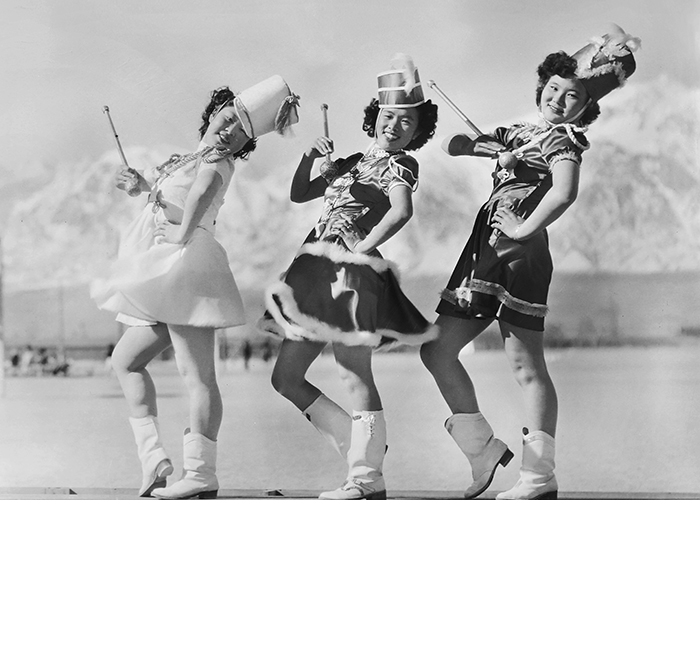

Toyo Miyatake, “Young girls practicing the baton in hopes of becoming majorettes. Even in the camps, the daily lives of the children didn't change,” c. 1942–45. Archival silver halide print. Courtesy of Toyo Miyatake Studio.

7 ⁄8

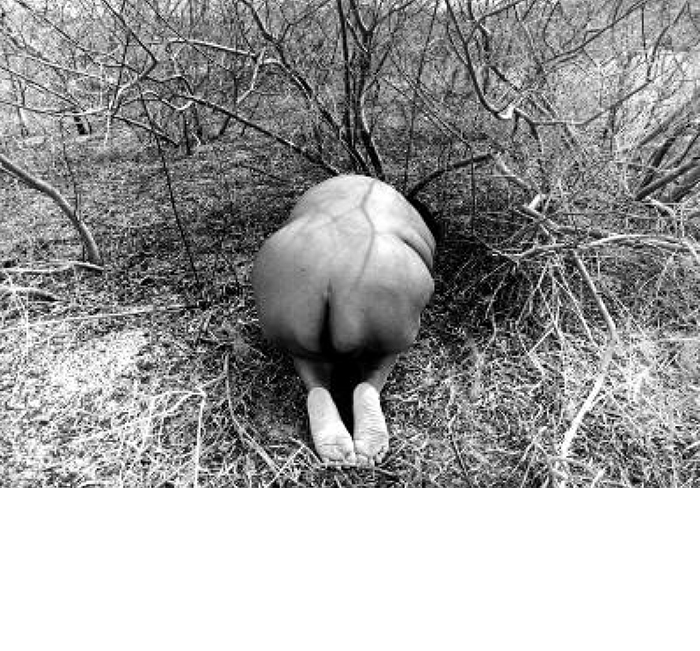

Laura Aguilar, Stillness #30, 1999. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy of Light Work, Syracuse, NY and The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

8 ⁄8

6 channel video installation and mixed media Courtesy of the artist.

“Photography offers an entry point to discussing complex issues,” says Fields. He believes images have the potential to incite violence or inspire progressive political action. He points to Jan. 6 as an event where images of the same political event were used by the left and the right to convey completely disparate meanings. “Throughout the exhibition you’ll find artists interrogating both the oppressive and liberatory potential of photographic vision.”

Fields cites Ines Schaber’s work Culture is Our Business as an example of how one can read into a single image to investigate the systems through which that image circulates. Schaber traces the journey of an image taken by Willy Römer during the German Revolution of 1918-19 as it moved through different public and private archives for over a century. The image depicts a street battle in Berlin, where a mixture of civilian revolutionaries and military fighters take cover behind stacks of newspapers. When the photographer’s exclusive copyright expired in 1929, the image became available for use in the public domain. Schaber discovered that the description of the photograph in various online image databases incorrectly identified the pictured combatants as members of the German government forces. She traced the source of this mislabeling to Bill Gates’s Corbis Archive, which accessioned Römer’s photographs. She maps the history of the image’s movement on a timeline and documents the precarious nature of institutional archives themselves when they are bought and sold by private holders and corporate entities.

In another series of photos titled Picture Mining, Schaber focuses on the Corbis Archive itself, photographing its physical location and the surrounding landscape. Near the town of Boyers in Western Pennsylvania, over 70 million pictures are stored in a former limestone mine.

FotoFest will exhibit FA’s ongoing investigation into police brutality at the Black Lives Matter protests. Incidences of police violence captured in videos and images were geolocated and verified, analyzed and categorized, and the resulting data presented in an interactive cartographic platform.

Activism on a more personal level is seen in the powerful works of pioneering Chicana artist Laura Aguilar. She celebrated her identity as a large-bodied, working class, queer Chicana woman and fought for access to mental health care and equity in the art world. The self-portraits in the series Stillness, which she created during a two-month stay in San Antonio in 1999, show her nude body at one with the arid landscape of Southwest Texas. There is a sense of reverence for her own body as well as the nature around it, a powerful communion of the physical and spiritual.

Through a wide range of practices, the artists of FotoFest 2022 pose questions and propose alternative ways to understand the role images play in our ideologically fractured time. “We consume thousands of images each day,” Fields reflects. “Why was this image made? For whom was it made? We are not suggesting that photography can provide solutions to the current issues, but we hope that this exhibition demonstrates the complexity of photography in regard to how it can aid in the manufacture of cultural and political ideologies, and conversely how it can respond to them.”

—SHERRY CHENG