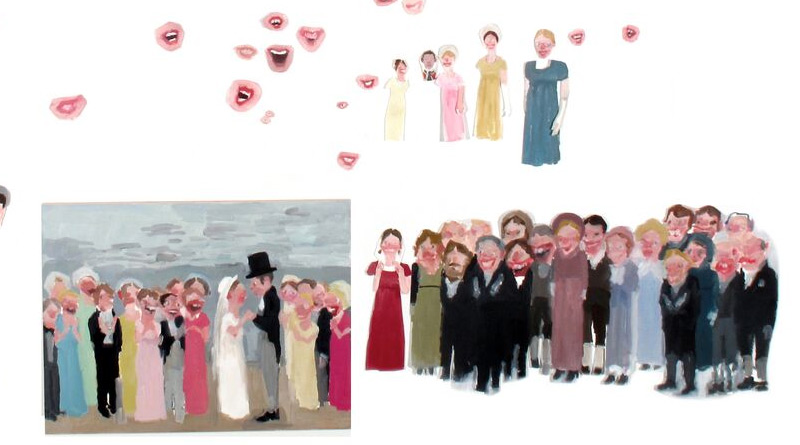

Jennie Ottinger Pride and Prejudice cutouts, 2016.

Jennie Ottinger at Conduit

Don’t fret. Jenny Ottinger is going to let us know how it ends. The San Francisco-based artist’s new show Spoilers is on view in Conduit Gallery’s Project Room through May 7. For the show the artist has recreated canonized literary reveals that include scenes from The Bluest Eye, A Hundred Years of Solitude, Jane Eyre, Black Boy and Lolita. These recreations are explored through oil painted paper cutouts and medium-sized paintings of scenes from fiction. Some pieces are anchored by a single painting, while discombobulated heads, mouths, eyes, and limbs float around the paintings.

That’s the real beauty of this particular show, by creating around the reveals, Ottinger exposes disheartening trends in modern literature that when viewed collectively, require their own modes of unpacking. Through her work, Ottinger reveals her own concerns with these works: women as martyrs, white narratives, and tiring Puritan constructs.

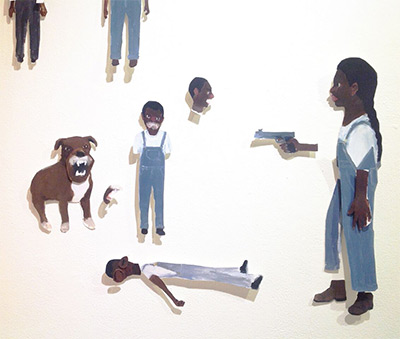

Unfortunately on occasion these deep questions become lost in the show, mainly due to the limitations of space, as well as the many issues Ottinger is mining. There are moments, due to proximity, that the individual pieces blend and blur, losing a bit of punching power and cohesion. But when breathing room is given, such as in the case of The Bluest Eye (installed at the end of the exhibition) the resonance of the central character, Pecola, a black body surrounded by leering mouths, speaks volumes.

2016, oil on panel, 16×20″.

Aesthetically, Ottinger’s paintings lie somewhere between half-recalled memories and ghost stories. Her work gives off a slight impression of speed and accident, but this is deceiving. The messy, rushed qualities are part of the charm, reflecting our own near-recollections of how these stories end. To get to the meat of Ottinger’s concerns, look to the faces of her painting’s figures. The grotesque, contorted mouths hold lies, eyes are smeared into blindness. Ottinger is making you think less about the importance of these “reveals” and more about who is writing them. As the show moves forward in time, and we explore writers of color such as Richard Wright’s Black Boy and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s A Hundred Years of Solitude, we find authors less concerned with peddling politeness, or explanations.

The accompanying paper cutouts, which dot the walls of the Project Space, deconstruct the linear approach to reading, creating instead a tapestry of truths. These pieces look tremendously tedious to install. The time spent in the space preparing is palpable. Like a novel worth reading, there is an investment of time being asked for here. Instead of relying on the age-old trope of reveal, Ottinger is showing us what came before, and what, potentially, can come after.

—LEE ESCOBEDO