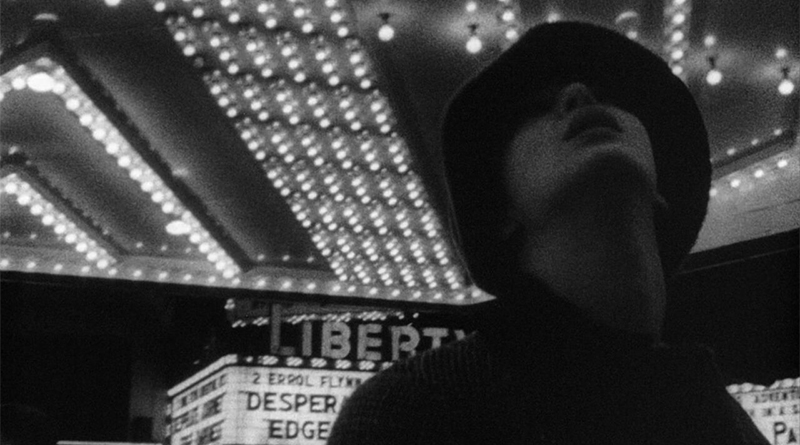

Shadows, directed by John Cassavetes, screens on June 3 at 7 p.m.

Photo courtesy of the MFAH.

at 7 p.m. Photo courtesy of the MFAH.

If there is a history of jazz, it’s forever incomplete, like archeologists finding fragments of text buried in the sand. Finding one is good, but no matter how many they find, there’s always some missing. If everyone got to take the History of Jazz course I took in college, where we watched Ken Burns’ Jazz, we still wouldn’t know shit about jazz.

The visual cataloguing of that history sometimes feels backwards. There’s so much we’re just now seeing (again)— out of print films restored and distributed, films that took years to make, prints assumed lost. Curated by Peter Lucas, The MFAH’s Jazz on Film series, June 3-24, is a reliable position to view the catalog continuing.

“I thought I had two strikes against me – being a woman and being black. Then I realized I had three strikes: I was playing a man’s instrument,” says Lucille Dixon in Lady Be Good; Instrumental Women In Jazz, screening on June 11. The story of women in jazz is typically told in a very abridged manner: Here are the three important singers, and here’s how their lives were sad, with maybe a footnote on Mary Lou Williams. Lady Be Good, directed by Kay D. Ray, lets the women who were there playing the whole time tell their own stories.

Lady Be Good is full of wonderful archival photographs, videos, and interviews. The rich interviews weave a homespun discourse on performance, novelty, and femininity. They explore the gaps between being themselves, presenting what the people and entertainment industry demanded, and the constraints of being a woman who played jazz. Many discuss how they learned to view the performance and manipulation of femininity as a necessary business skill. They discuss the challenges they faced, such as arbitrary definitions of “ladylike” instruments and battles for autonomy with management. Female USO performers were expected to accompany men to balls; they thought that was unacceptable and pushed back and won. The story that emerges is full of passion, confidence, and reverence for their important contribution to music.

Ray worked on the film for 20 years, and it shows. It’s handmade and heartfelt. If she wasn’t there to capture the stories, I don’t know if anyone else could, because anyone who can testify to that time is gone or will be gone soon enough.

One ongoing source of hopeless confusion is our ignorant and shortsighted explanations for “the behavior of the artist.” Was Monk eccentric? Or is eccentricity a shortcut to define him and make his memory digestible. What is a gimmick, after all? Rahsaan Roland Kirk is remembered by some for playing several saxophones at once. He was an outspoken activist, which some people might say is “eccentric.” In Adam Kahan’s film, The Case of the Three Sided Dream(June 17), Kirk and those who knew him are given enough time to explain and clarify his intentions, frustrations, and convictions, leaving no mystery but the needed mystery. Most importantly, he makes clear: there is no gimmick. It’s all part of his relentless pursuit of sound and music. In between candid home movies, and a wealth of quality performance footage, Rahsaan explains his world, his vision, his blindness, and most importantly, his dreams. His name, the horns, the sounds; almost everything belonged in his personal “religion of dreams.” His concern was the music and the fate of the music. He did what he could to ensure that jazz, which he preferred to call “black classical music,” would not be forgotten by America. He’d be sad to know where we’re at with that.

Shadows (June 3), John Cassavetes’ first film, begins with a distorted, crunching swing, too loud for the tape, which probably cheap because it was his first film. The frame is full of bodies or faces, or half bodies. They’re alive, and maybe too alive.

It’s a case history of people cooking under pressure, not in the right or wrong, but stuck somewhere in the middle struggling to cope. It follows a family that exists on a continuum of blackness: Hugh, played by Hugh Herd (who is black), is the black brother, Benny, played by Ben Carruthers (who is 1/16th black and used a sunlamp to tan for the part), is just barely black enough, and Lelia, played by Lelia Goldoni (who is white), is just white enough to be white or black, producing most of the film’s racial friction. It’s an oblique way of examining race, but it works. Hugh and Benny are interesting characters, but they’re ultimately static, leaving Lelia left shipwrecked in the emotional depths. This is where Goldoni and Cassavetes shine, dissolving traditional emotional narrative into fractured, honest fragments of thought, mood, tone, and tension. One minute someone’s dicking around at the bar drinking, and the next we are full of dread, and then we’re okay for a while, until we’re at home with him in the dark. The excellent Charles Mingus score and the shoddy, haphazard sound design are part of the DIY Cassavetes charm. He has no reservations cutting from the claustrophobic roar of a mic in a busy room to a silent street with dubbed dialogue. Shadows set American Independent film, and the father of it, Cassavetes, in motion.

Shadows is great and everyone liked it, so Cassavetes goes to Hollywood to make Too Late Blues, screening on June 4. It’s a very “Hollywood” film, ruined according to him by shortened shooting schedules and casting decisions. It and A Child is Born, the next Hollywood disaster he agreed to make, remain excluded from the Cassavetes canon.

Bobby Darin gives an acceptable and lukewarm performance as Ghost, an artist devoted to his music, seeking recognition, unwilling to compromise, rarely shown working on his art, managing to spend most of his time seeking, but not very effectively, the love of Jess, a could have been jazz singer played by Stella Stevens (Gena Rowlands would have been better).

So it’s fitting! Go home John, it won’t work out. The movie isn’t bad, it’s not even close to bad, just a bit too slick, contained, predictable, and forgettable. Despite the Hollywood polish, Cassavetes’ shadow hangs over scenes, especially the private moments filled with a natural, fluid rhythms of emotion, impulse, and tension. The David Raksin score is good. Not everything has to be a masterpiece and there’s something to checking into “minor works,” and finding where they fit on the trajectory.

Jazz on Film also features: The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith (June 10), a new documentary about Jazz photographer Eugene Smith’s experience documenting the “Jazz Loft” in 1957; The Amazing Nina Simone(June 24), a new documentary chronicling the often misunderstood career and life of singer Nina Simone; and All Night Long (June 18), a “jazzy” retelling of Othello from the 1960’s.

—JOE WOZNY