The best parts of horror movies are always the early scenes, when a director can revel in the shadows and tease us with glimpses of the monster, allowing our brains to fill in the blanks. The things we are afraid of, so specific and personal, are vastly more terror-inducing than anything a CGI artist can dream up. Over the course of her career as a painter, Kelli Vance has infused her works with this kind of “cinematic” energy, giving us just what we need to be titillated, suspicious, or terrified. Her new works, eight paintings created over the course of five months, form an exhibit at Cris Worley Fine Arts titled We Don’t Sleep, on view through May 21-June 25.

Vance’s process involves photographing herself in various costumes and wigs, usually procured from online thrift stores or consignment. “You can get cool, weird stuff there,” she says. Then she carefully controls the lighting and environment, just like a film director. “I take a shitload of pictures,” she laughs. “There’s usually a posture that hits just right.” When she’s satisfied with the source material, she weaves inspiration from “two or three photos” into a single painted image.

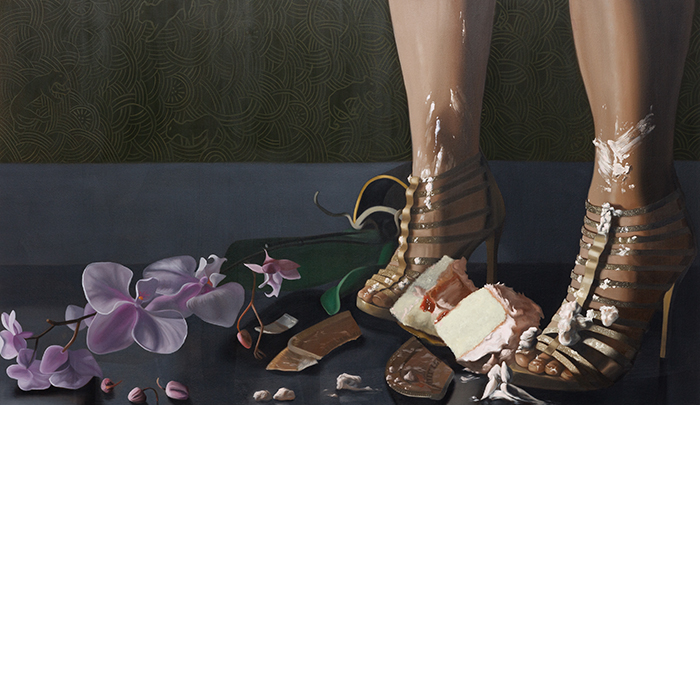

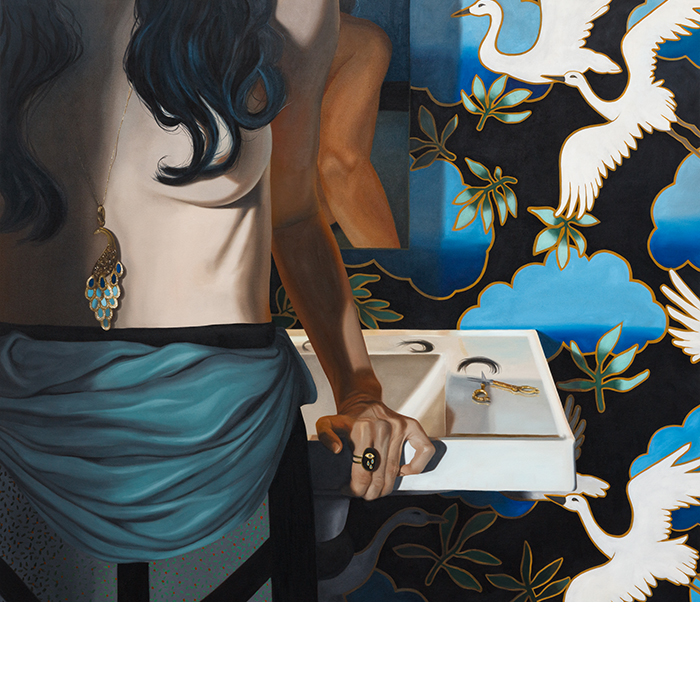

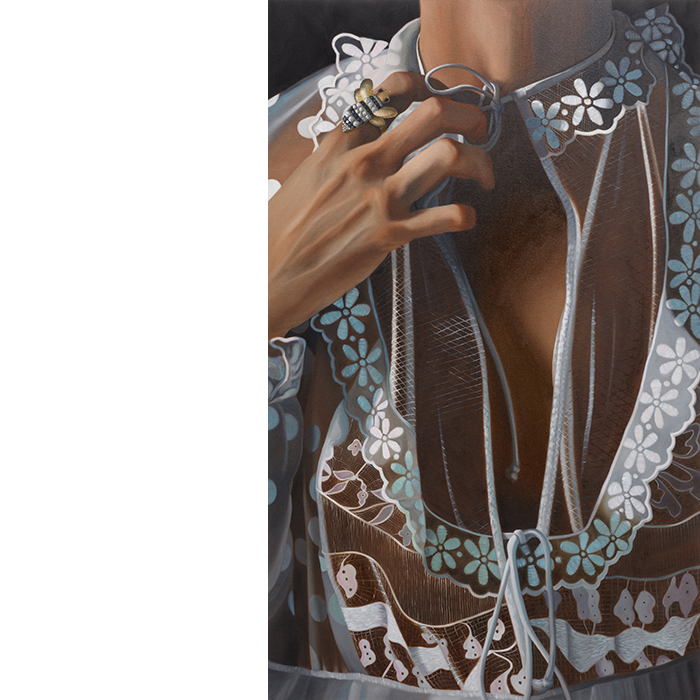

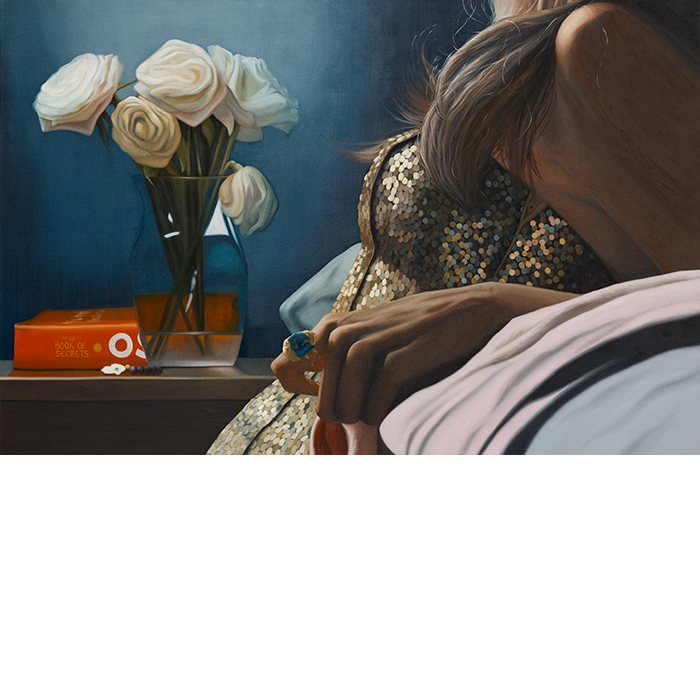

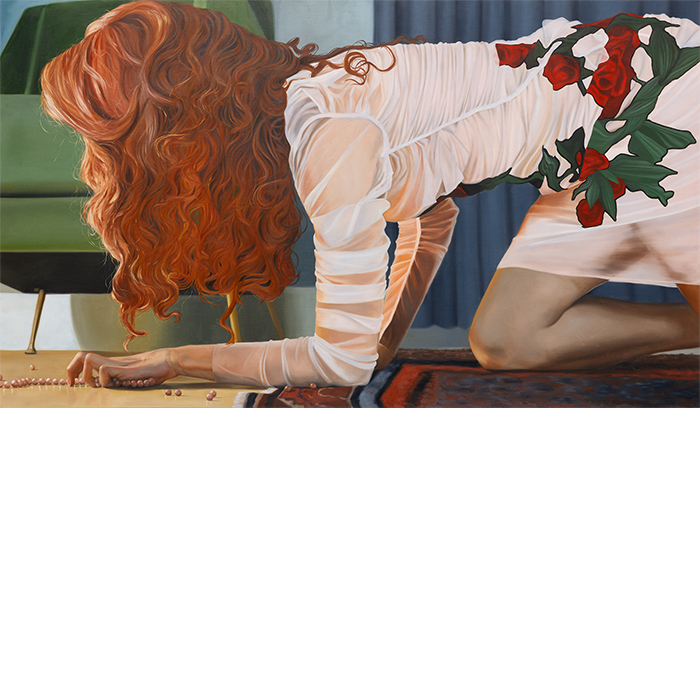

The body of work for We Don’t Sleep is classic Vance-ian noir, but also a bit of a departure. The painting’s size and close-cropped vantage points crowd the viewer in, where we can contemplate the pattern of lace knotted between taut fingers, or the nacre glow of a snapped string of pearls as they roll across the floor. “I started to embrace my love of fabric,” she says of these paintings. “My mom used to make my clothes,” she explains. “I was pretty tomboyish growing up. I always struggled with femininity and what that was supposed to look like.”

Although Vance has left out some identifying characteristics, these works are informed by a deeply personal history. To tap into the necessary emotion, she explored her own childhood fears. “When I was growing up, my dad was a police officer,” she says, describing the sense of “veiled…unpredictability and threat” that came along with that. Her deep concern for her dad, combined with a lack of information about what he did when he left the house was experienced as a kind of trauma. “I only knew that bad things could happen,” she says.

1 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

Close to the Bone, 2022

oil on linen

48h x 36w in

2 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

It Could Have Been Different, 2022

oil on canvas

42h x 72w in

3 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

Like So Many of Her Untold Stories, 2022

oil on canvas

60h x 68w in

4 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

She Came Upon the Noonday Demons, 2022

oil on canvas

58h x 36w in

5 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

Shelter in the Shadow, 2022

oil on canvas

56h x 66w in

6 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

All That Glitters, 2022

oil on canvas

42h x 64w in

7 ⁄8

Kelli Vance

That Melancholy Residue of Desire, 2021

oil on canvas

60h x 40w in

8 ⁄8

The Gut Wrenching Beauty Of It All, 2022

oil on canvas

42h x 71w in

In many ways, the characters in Vance’s paintings appear moneyed and decadent. With such lush surroundings and beautiful clothing, what could these wealthy white women be so worried about? Bringing us close, Vance emphasizes the way that fear contracts one’s world to the point of being unable to see beyond their own frame of reference. Maybe the scariest part of these paintings isn’t outside the frame after all. The fear is real, but it also has the possibility of transforming us into the monster.

—CASEY GREGORY