Installation view. From left to right: Lucia Simek, The Rods, 2012 – present (Visible storage is in the background),

Ryan Goolsby, Untitled, 2015

Kevin Todora, Untitled Landscape 3, 2015 and Untitled Landscape 1, 2015

Ryder Richards, Work/Play: Raft, 2015

Cassandra Emswiler Burd, Florida, 2013.

Photo by Kevin Todora.

If you know Latin, you know the phrase lorem ipsum is an abbreviated version of dolorem ipsum which translates to “pain in and of itself,” a darkly poetic line penned by Cicero. Designers and editors, however, recognize the words as the first two used as “filler text”: a substitute for actual content to come later. But I digress.

Lorem Ipsum is also the name of a show on view at SMU’s Pollock Gallery through Dec. 12. The brainchild of Pollock Curatorial Fellow Danielle Avram and co-curated by UTA’s Benjamin Lima and New Orleans’ curatorial collective Pelican Bomb, Lorem Ipsum portends to draw back the curtain, in a sense, on the role of the curator by challenging the primacy and permanency of the art exhibition.

The show strives to critique the idea of what it means to be a curator, and what it is a curator does, by hosting, in the inevitable context of an exhibition (an art world artifice which is also challenged by Avram’s thesis), a running dialogue between the three curators (only some of which the audience is privy to) and an “exhibition” which will evolve over its run to showcase three different curatorial approaches.

Utilizing the exquisite corpse as a jumping off point, Avram et al. are essentially attempting to illustrate the role of collaboration and chance in informing the creation of an exhibition while exploring how one might illustrate the decision-making, or process that goes in to a “finished” product.

There are, of course, simple ways to reveal the curatorial team’s hand; leaving behind remnants of a previous installation in a current installation, moving artwork around during the span of the show, inviting viewers to watch the installation process, or encouraging transparency around the notion of a “finished product” by having artists re-work their installations, all of which Avram and team utilize. But anything easy is also obvious. What about the idea? How do curators determine how best to illustrate the exhibition’s thesis? And how can a curator make that process visible?

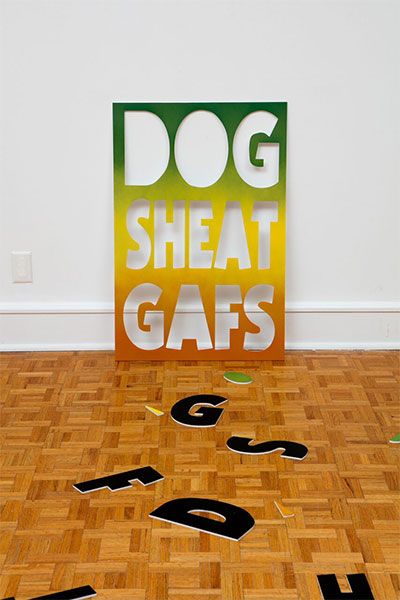

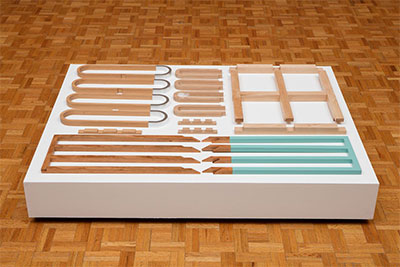

Avram, for her part, curated pieces that are both figuratively and physically fragmentary. Take, for example, Shelby David Meier’s Not Getting What We’re Getting At, a poster made of MDF whose letters have been seemingly haphazardly punched out and scattered on the floor—a piece in which possibility is inherent to the structure: Might not the letters have been scattered another way? Ryan Goolsby’s Untitled is another; Goolsby has positioned the wood and enamel with which he might typically begin a project as the project, leaving the viewer wondering if the piece is truly finished or if it might instead be a work in progress.

A site-specific installation of rolls of astro-turf by Ryder Richards on view when I saw the show during its first week actually was a work in progress; later in the week Richards returned to tweak the piece, implying the possibility for further alterations and the refusal of finality.

With these works presented alongside an atmospheric but seemingly subject-less video piece by Cassandra Emswiler Burd, and Kevin Todora’s abstract takes on contemporary photography, Avram seems to be using the artist’s work, whether it is physically or conceptually fragmentary, to present viewers with a series of unanswered questions concerning process and finality. Experimentation and process are, of course, the subject of much contemporary art; although diverse in form, these are works that all seem either frozen in process, potentially unfinished or at least full of potential either physically and conceptually. In Lorem Ipsum, that tendency in art is harnessed to speak as well to the role of process in curation; although we may not think of it as such, experimentation, chance and irresolution are also central to the exhibition.

The work which was on view in the exhibition’s first iteration questions the concept of finality in contemporary art, and therefore, the possibility of a conclusion in 2015: If everything is and has been contemporary, and history itself is perpetually open to revision, the idea of the exhibition as isolated, complete incident is dead, its true impact to be tweaked and refined forever. The process, the lack of finality Avram believes is central to the 21st century exhibition is illustrated through visually open-ended, process-driven art.

Lorem Ipsum declares, in its title, its intention: To draw the viewer’s attention away from the theoretical curatorial theses (the realm of the curator) and to focus it instead on the process as design, with the hope that the context becomes part of the subject; to imply the influence of exterior factors, perhaps most importantly the mind of the artist, on what a visitor sees in a gallery. While the nature of contemporary art and an audience’s acclimation to seemingly-unfinished art hampers the exhibition’s success, the questions Avram is asking and the methods she is using to explore them are important as the art world continues to grapple with art that is increasingly visually obscure. Perhaps Lima is right, the process is and should be part of the story, and it is time for curators and artists alike to recapture and refine their roles as storytellers by telling the whole story.

—JENNIFER SMART